More Than A Wall Corporate Profiteering and the Militarization of US borders

Temas

Regiones

This report examines the role of the world’s largest arms (as well as a number of other security and IT) firms in shaping and profiting from the militarization of US borders. Through their campaign contributions, lobbying, constant engagement with government officials, and the revolving door between industry and government, these border security corporations and their government allies have formed powerful border–industrial complex that is a major impediment to a humane response to migration.

Descargas

-

More Than A Wall: Corporate Profiteering and the Militarization of US borders (PDF, 6.03 MB)Tiempo medio de lectura: 80 minutes minutos*

-

More Than A Wall: Executive summary (PDF, 1 MB)Tiempo medio de lectura: 10 minutes minutos*

Autores

Executive Summary

US President Donald Trump’s obsession with ‘building a wall’ on the US- Mexico border has both distorted and obscured public debate on border control. This is not just because there is already a physical wall – 650 miles of it – but because Trump’s theatrics and the Democrats’ opposition to his plans have given the impression that the Trump administration is forging a new direction on border control. A closer look at border policy over the last decades, however, shows that Trump is ratcheting up – and ultimately consolidating – a long-standing US approach to border control.

Download the full report here.

This report looks at the history of US border control and the strong political consensus – both Republican and Democrat – in support of border militarization that long pre-dates the Trump administration. It shows how this political consensus has been forged to a significant degree by the world’s largest arms (as well as a number of other security and IT) corporations that have made massive profits from the exponential growth of government budgets for border control. Through their campaign contributions, lobbying, constant engagement with government officials, and the revolving door between industry and government, these security corporations and their government allies have formed a powerful border–industrial complex. The evidence shows that it is these corporations – and their role in border infrastructure and policies – that have led to a predominantly militarized response to migration and thereby become the single biggest impediment to a humane response to migration.

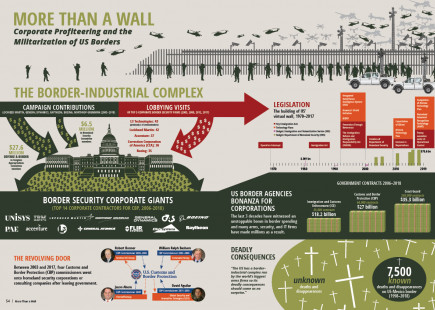

Click on image for full size infographic: https://www.tni.org/files/more-than-a-wall-report-infographic.jpg

LONG HISTORY OF BOOMING BUDGETS FOR BORDER MILITARIZATION

The report begins by tracing the history of border control and militarization. It shows how US budgets for border and immigration control massively increased from the mid-1980s, a trend that has been accelerating ever since. These budgets rose from $350m in 1980 (then run by the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS)) to $1.2 billion in 1990; $10.2 billion in 2005 and $23.7 billion in 2018 (under two agencies, the Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)). In other words, budgets have more than doubled in the last 13 years and increased by more than 6000% since 1980. This growth was matched by a similar growth in border patrol from 4,000 agents in 1994 to 21,000 today. Under its parent CBP agency (which includes an Office of Air and Marine, investigative units, and the Office of Field Operations) there are 60,000 agents, the largest federal law- enforcement agency in the United States.

Importantly, it shows that modern US border control involves much more than a wall. The physical barriers on which Trump focuses for campaign purposes are but one feature of an extensive technological border-control infrastructure that penetrates deep into the US interior and into the border regions of Mexico as well as countries in Central America and the Caribbean and beyond. Since 1997, the US government has been steadily expanding the use of surveillance and monitoring technologies, including cameras, aircraft, motion sensors, drones, video surveillance and biometrics at the US–Mexico border. Border Patrol agent Felix Chavez, speaking at the Border Management Conference and Technology Expo in El Paso in 2012, acknowledged this border arsenal, saying that ‘in terms of technology, the capability we have acquired since 2004 is phenomenal’.

In line with the 1946 revisions to the Immigration and Nationality Act – and a 1957 decision by the Justice Department – border-control measures extend 100 miles inland, thus expanding the market for the border industry to an area where more than 200 million people, two-thirds of the US population, reside. This is reinforced by US Border Patrol strategies that emphasize a ‘multi-layered’ approach to patrolling the border. What is more, an active policy to externalize US border enforcement to prevent migrants getting anywhere near US borders – particularly since 9/11 – means there are both funding and active programs to train foreign border guards and transfer resources and infrastructure to other countries for border policing. Elaine Duke, Deputy Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), has called these international programs ‘the away game of national security’.

This has created a seemingly limitless market for border-security corporations. For example, VisionGain argued in 2014 that the global border-security market was in an ‘unprecedented boom period’ due to three interlocking developments: ‘illegal immigration and terrorist infiltration’, more money for border policing in ‘developing countries’, and the ‘maturation’ of new technologies. MarketAndMarkets projects that this will be a $52.95 billion market by 2022.

While this is a process taking place in many regions – see TNI’s Border Wars reports on border policies in the European Union (EU) – the US provides the single largest market for border-security corporations, which have reaped handsome rewards under Democrat and Republican administrations alike.

CORPORATE PROFITS FROM BORDER MILITARIZATION

The report unveils the scale of the revenues this border-security bonanza has provided, mainly to US corporations:

- ICE, CBP and Coast Guard together issued more than 344,000 contracts for border and immigration control services worth $80.5 billion between 2006 and 2018. ICE issued more than 35,000 contracts (costing $18.2 billion), CBP more than 64,000 ($27 billion), and the Coast Guard more than 245,000 ($35.3 billion). CBP contracts alone between 2006 and 2018 exceed the accumulated INS budgets from between 1975 and 1998 of approximately $26.1billion. They are also certainly less than the true figures, as reports by the US Office of the Inspector General (OIG) reports have consistently criticized these departments for their poor data transparency.

- Focusing in on CBP contracts – the largest government contractor in border and immigration control – the report identifies 14 companies that are giants in the border security business. These are Accenture, Boeing, Elbit, Flir Systems, G4S, General Atomics, General Dynamics, IBM, L3 Technologies, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, PAE, Raytheon, UNISYS, among several other top firms we list in the report that are receiving contracts. They include technology and security firms, but are clearly dominated by the same global arms firms that reap rewards from high levels of US military spending. In addition, it also profiles, private prison companies CoreCivic and Geo Group who along with G4S are major players in providing immigration detention services.

- The volume and value of CBP contracts has grown to the point that in 2009, Lockheed Martin landed a contract potentially worth more than $945 million for maintenance and upkeep of 16 P-3 surveillance planes equipped with airborne and surface-to-radar systems. This one contract was equal to the total entire border and immigration enforcement budgets from 1975 to 1978 (around $923 million). Similarly, the contract to the San Diego-based General Atomics, worth $276 million in 2016 for the operational maintenance of the Predator B drone systems, almost exceeds any of the INS annual budgets in the 1970s.

- The money paid out to corporations dwarfs that given to humanitarian groups supporting refugees. For example, in 2016 the Office for Refugee Resettlement designated $14.9 million to nine non-profit agencies to help people resettle, a tiny fraction of the total contracts given to corporations to stop, monitor, arrest, incarcerate and deport people.

- Ethical scandals involving some of the big ten border-security corporations have done little to slow down the revenue stream. UNISYS was found guilty in 2005 of over-billing taxpayers for almost 171,000 employee hours; Flir Systems was found guilty of bribery in 2015; G4S has faced charges for mistreatment and even the death of detainees in the US and UK.

Tracking US government contracts for border-security operations overseas is harder to calculate as they are disbursed by multiple agencies through more than 100 programs. The report shows, however, that Raytheon is one of the most significant players – receiving over $1 billion between 2004 and 2019 from the Defense Threat Reduction Agency – which has included significant border-building operations in Jordan and the Philippines. According to Raytheon’s own sources, it has deployed border ‘solutions’ in more than 24 countries across Europe, the Middle East, Southeast Asia and the Americas, covering more than 10,000 kilometers of land and maritime borders. This included deploying more than 500 mobile surveillance systems, training more than 9,000 members of security forces, and building 15 ‘sustainment centers’.

Corporations have not been the only ones to benefit. Universities and research institutes have also cashed in through nine Centers of Excellence (COEs) on Borders, Trade, & Immigration that in 2017 received $10 million directly, with another $90 million dedicated to research and development (R&D). The University of Houston, University of Arizona, the University of Texas El Paso, University of Virginia, West Virginia University, University of North Carolina, University of Minnesota, Texas A&M, Rutgers University, American University, the Middlebury Institute of International Studies, and the Migration Policy Institute all receive DHS funding. According to the DHS, these COEs have developed more than 100 targeted tools, technologies, and knowledge products for use ‘across the homeland security enterprise’. The COEs have received $330 million of additional investment from ‘external sources’, presumably the private sector, for homeland security research, development, and education. Other research corporations working with the COEs include MITRE, SAS and Voir Dire International, LLC.

THE CONSOLIDATION OF A BORDER–INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX

The report shows that corporations’ success in winning ever bigger contracts is not an unexpected bonanza, but has been engineered by the same corporations’ growing involvement in US politics. The main beneficiaries of border contracts are also the same companies making the most campaign contributions, doing the most lobbying, meeting most often with government officials, and entering government as advisors and staff in strategic positions of influence. In this way, they have shaped the border-militarization policies from which they have profited.

With data from the opensecrets.org database – run by the Center for Responsive Politics – the report reveals that:

- The border-security corporate giants are also the biggest campaign contributors to members of the House Appropriations Committee, the congressional body that regulates expenditures of the federal government, or earmarks the money for potential contracts. Between 2006 and 2018, Lockheed Martin, General Dynamics, Northrop Grumman, Raytheon, Boeing contributed a total of $27.6 million to members of the committee. During the 115th Congress (2017–2018), Northrop Grumman and Lockheed Martin were the top two contributors with $866,194 and $691,401 respectively offered to members of the Appropriations Committee, along with Raytheon, Boeing, Deloitte, and General Dynamics, all making donations of over $500,000. While these were all companies winning military contracts and were also lobbying on military issues, they also received substantial contracts from CBP.

- The top seven contributors to the House Appropriations Committee members (2017–2018) are all CBP contractors: Northrop Grumman, Lockheed Martin, Honeywell International, General Dynamics, Deloitte LLP, Boeing, and Raytheon.

- The border-security corporations also make the biggest campaign contributions to members of the strategic House Homeland Security Committee, which handles legislation on border and immigration control. Between 2006 and 2018, Lockheed Martin, General Dynamics, Northrop Grumman, Raytheon, Boeing contributed a total of $6.5 million to members of the committee In the 115th Congress (2017–2018), Northrop Grumman donated $293,324, General Dynamics $150,000 and Lockheed Martin $224,614.

- Unsurprisingly, the positions of politicians on these committees frequently align with the interests of their corporate donors, regardless of party affiliation. Texas Democrat Henry Cuellar, for example, was one of many Democrats in 2018 who argued in the media for technological solutions to border security. He failed to mention, however, that his largest campaign contributors came from GEO Group and CoreCivic ($55,690), Northrop Grumman ($13,000), Boeing Corporation ($10,000), Caterpillar Inc ($10,000) and Lockheed Martin ($10,000) – all of which would benefit from government investment in border security.

- Lobbying on homeland security – of which border militarization is a significant part – has increased significantly in the last 17 years, involving many of the border-security corporations. In total, from 2002 to 2019 there were nearly 20,000 reported lobbying visits related to homeland security. In 2003 Northrop Grumman was the top lobbyist, reporting five lobbying visits where it was one of 385 clients with 637 reported visits. “Clients” refer to either the companies (such as Northrop Grumman) or separate firm that supplies a representative to one of those companies. “Visits” refer to the number of times that a client visit a congress member, a policy maker of some sort, to advocate or push for some sort of legislation or policy or the allocation of money in the annual budgets. In 2006, this more than doubled: 724 clients with 1,428 reported visits, led by Lockheed Martin, Accenture, Boeing, Raytheon, and Unisys. And in 2018, there were 677 clients with 2,841 visits listed: including top CBP and ICE contractors Geo Group, L3 Technologies, Accenture, Leidos, Boeing, CoreCivic, and also companies such as Facebook, Microsoft, and Visa.

- The extent of the lobbying can be seen in the efforts of the top CBP contractors for the 2018 Department of Homeland Security Appropriations Act (H.R. 3355). By the time, it was signed by the president on 23 March 2018, it would be the largest border and immigration budget in US history at more than $23 billion (the sum total for CBP and ICE). In support of the bill, representatives of General Dynamics lobbied 44 times, Northrop Grumman 19, Lockheed Martin 41 and Raytheon 28, in addition to a number of other lobbyists representing these firms and other border-security giants including L3 Technologies, IBM and Palantir. The lobbying groups massively outstripped the few advocacy and civil society organizations (CSOs) such as the Lutheran Refugee Service. The result in 2018 was the approval of the Omnibus Appropriations bill, which increased border-control budgets everywhere: the DHS budget was up by 13% at $55.6 billion, $16.357 billion for CBP (a 15% increase), and $7.452 billion for ICE. The latter included funding for 40,520 detention beds per day, up by 1,196 from FY 2017. In 2017, CoreCivic Inc. reported $840,000 in total lobbying, through four different firms, mainly for federal budget and appropriations. Geo Group reported close to $2 million in lobbying in 2017 through six different lobbying organizations.

- This gives only a partial picture as a great deal of lobbying also takes place behind closed doors, especially on issues that are controversial, such as immigration. It also includes other forms than the registered lobbying visits. For example, between 2000 and 2005, General Atomics spent around $660,000 on 86 trips for legislators, aides, and their spouses to build support for its business.

Along with constant lobbying and campaign contributions, the border-security giants also build powerful and fruitful relationships through their constant interactions with government officials. One of the key arenas for this are the now annual Border Security Expos that since 2005 have brought together industry executives and top officials from the DHS, CBP, and ICE. The event currently includes a pre- Expo golf day where Homeland Security and industry executives can meet casually and discuss future prospects and possible contracts.

As well as providing a place for border-security corporations to hawk their wares, and promote their latest technological ‘solutions’, their seminars also encourage a common perspective, language and policy approach. This is backed up by the personal networking at lunches, coffee breaks and dinners that will cement cooperation for years to come. Panels at the 2020 Expo in San Antonio include titles such as ‘Identify and address new and emerging border challenges and opportunities through technology, partnership, and innovation’, ‘Mass Migration and Unaccompanied Children: Financial and National Security Impacts’ and ‘Border: Wall – Ports – System(s) – Technology – Infrastructure – Integration – Modernization’. The US Expos are paralleled in similar events across the globe, such as the Expo de Seguridad in Mexico City, Milipol in Paris and ISDEF in Tel Aviv.

As if relations between industry and government were not close enough, there is also a revolving door between corporations and government. Ex-government officials are often head-hunted by various corporations, or enter the lobbying industry – as not only lobbyists, but also as consultants and strategists.

- Between 2006 and July 2019, 177 people have gone through the DHS revolving door and 34 have worked both for the House Homeland Security Committee and for a lobbying firm.

- Between 2003 and 2017, at least four CBP commissioners and three DHS Secretaries went onto homeland security corporations or consulting companies after leaving government.

- Robert Bonner, for example, after his time as the first CBP commissioner (2003–2005), went on to join the Sentinel HS group, a Washington-based homeland security consulting firm. In 2010, CBP issued Sentinel HS a $481,000 contract to do ‘strategic consulting’ over five years. This included facilitating ‘discussions among senior Border Patrol leaders’ at forums and conferences near CBP headquarters in Washington.

The government–industry relation has become so tight and so blurred that some government officials no longer see any distinction. At a SBInet Industry Day in 2005, Michael Jackson, the Deputy Secretary of the DHS, who had previously been Lockheed Martin’s Chief Operating Officer, addressed a conference room full of would-be contract recipients: ‘this is an unusual invitation. I want to make sure you have it clearly, that we’re asking you to come back and tell us how to do our business. We’re asking you. We’re inviting you to tell us how to run our organization’.

It is no exaggeration to say that the US has a border–industrial complex as powerful as the military– industrial complex which President Eisenhower famously warned against in 1961. Indeed, many of the corporations are the same players, shaping not only military policy and procurement, but also increasingly border and migration policy. So, it is hardly surprising that a militarized and repressive approach to border and immigration control dominates US politics.

In this context, Trump’s election, with his deliberately polarizing rhetoric on immigration and his support for militarized borders, provides a definite boost to the industry – albeit offering no significantly new direction. Certainly, industry has openly welcomed the increase in budgets. CBP budgets have gone from $14,439,714 in 2017 to $16,690,317 in 2019, an increase of more than $2 billion to spend on more contractors, both new and existing. ICE has also seen a nearly $2 billion increase over the same period. As the report details, however, this growth largely follows a long trajectory of border militarization that has seen a constant ratcheting up of budgets and borders over many decades.

While the focus of this report is on the corporate profit made from the massive expansion of the border industrial complex, the consequences are felt in human lives, most of all the widespread, and intentional crisis of death and disappearance in the borderlands. In their introduction to the Disappeared report series, the border humanitarian organization, No More Deaths, which has co-sponsored this report writes, “Over the past 20 years, the US has armored border cities with walls, cameras, sensors, personnel, and military-style infrastructure...As a result, border crossers now enter the US through remote rural areas, fanning out across the backcountry region north of the border and carving a complex web of trail systems through mountain passes, rolling hills, desolate plains, and dense brushlands.”

The creation of an ever more deadly journey means that “thousands of people have perished in the borderlands due to dehydration, heat-related illness, exposure, and other preventable environmental causes. Extreme heat and bitter cold, scarce and polluted water sources, treacherous topography, and near-total isolation from possible rescue are used as weapons of border enforcement.”

So for concerned citizens, who have been rightly horrified by the policies pursued by the Trump administration towards migrants, it means that it is not enough to replace Donald Trump in order to establish more humane US policies on migration. The militarization of US borderlands has a long history which has been entrenched by the corporations that thrive from it. The revenues and profits of extremely powerful business interests depend on an ever-expanding market for border control and militarizatio. These border-security giants exercise strong influence on Republican and Democrat politicians in strategic positions in the executive and legislature as well as in key media positions. Any strategy to change the direction of US policy on migration will require confronting this border–industrial complex and removing its influence over politics and policy. For while those corporations who profit from the suffering of migrants remain embedded in positions of power within government and society, it will be a huge challenge to forge a new approach that puts the lives and dignity of migrants first.