The 'new Darwinian world' of the energy transition CATL, capitalist strategies and emerging state-capital alliances

Topics

This longread examines CATL’s rise during China’s capitalist boom and explores its global strategies for securing raw material supplies and market access, featuring case studies from Indonesia and Hungary. We conclude by posing questions for further research on the less visible yet crucial actors in EV supply chains. This is the first in a series analyzing CATL's global accumulation strategies.

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

Carmakers, miners and battery groups are jostling to position themselves in the new Darwinian world [...] We may be coming to a world in which the market becomes very brutal. There will be a small number of winners, a lot of losers and a lot of blood on the floor1

The company is also particularly interesting because of how it straddles multiple activities across the EV-supply chain. Despite this globally significant role and while often covered in business publications, it remains somewhat under the radar of social movements. It is neither a classical mining company (which, as mentioned, is typically the target of anti-mining groups) nor a company that is visible to consumers, because its profit is derived from the production of intermediate goods that it sells on to other capitalist actors, notably the carmakers. Mapping of CATL’s investment practices and strategies can help in ‘connecting the dots’ through identifying the diverse constituencies that are implicated in and/or impacted by the company’s activities. Such mapping is a first step in forging new alliances and opening up new opportunities for solidarity, learning and hopefully mobilizing and organizing across the transnational EV-supply chains – from the mining sites to the car factories. Finally, CATL’s history and rise to one of the central actors in the contemporary EV-supply chain is an important ‘window’ into how companies generally are navigating the above-mentioned geopolitical tensions and what some are calling a new phase of state-capitalism.5 With its global web of activities related to extraction, production and exchange, CATL has to carefully navigate its ties with different states and thereby gives insight into various state-capital alliances.

It should be said here at the outset though, that we can only begin to scratch the surface of this vast global web. Our analysis centers on outlining CATL’s rise amidst China’s ‘capitalist boom’ before turning to its global strategies related to supply of raw materials and market access through short peeks into the cases of Indonesia and Hungary. We conclude by asking what we consider to be pertinent questions for further research on the less visible – though no less important – actors within EV supply-chains. This is the first piece in a series that will more closely examine CATL's global web of accumulation strategies.

China’s capitalist boom, EV-battery dominance and CATL

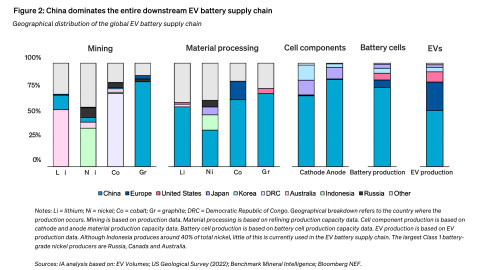

China produces three-quarters of all lithium-ion batteries and is home to 70% of production capacity for cathodes and 85% for anodes (both are key components of batteries).6

Today, Chinese actors play a pivotal role in the transnational EV-battery supply chains – and especially the downstream segments, meaning those activities coming after the initial "upstream" mining activities, which are the point of departure of the supply chains (see Figure 2).

Source: IEA. All rights reserved. See: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/4eb8c252-76b1-4710-8f5e-867e751c8dda/GlobalSupplyChainsofEVBatteries.pdf

Chinese actors’ current dominance within these particular supply chains needs to be seen in the context of what Ho-Fung Hung has called China’s ‘capitalist boom’, which he periodises from 1980-2008. Within this longer period, Hung emphasizes the early 1990s as a pivotal period where a new political consensus within the party-state was reached based on “uncompromising authoritarian rule combined with equally uncompromising marketization … setting the tone of China’s development path in the 1990s and beyond.”7 Through this consensus, the state itself underwent a transformation now geared towards defending the private accumulation of capital in a market system and suppressing resistance to this accumulation process. It was this environment that allowed for the rise of China’s ‘new rich’, including “the cadre-capitalist class, self-made businessmen, middle-class professionals and the like”.8

It is amidst these political-economic transformations that the birth and rise of CATL should be understood. CATL’s founder and CEO, Robin Zeng is exactly one of these ‘new rich’ – with his current estimated net worth just under USD 27 billion making him number 6 on Forbes’ China Rich List and 68th richest man in the world. In the early 1990s, Zeng was working for the Japanese electronics company TDK9 in a Hong Kong-subsidiary. In 1999, he established ATL to focus on battery production for mobile phones with two TDK co-workers. Characteristic of the role of neighbouring capital as source of Foreign Direct Investment in this capitalist boom-period, TDK then bought ATL in 2005 for USD 100 million, keeping it on as a subsidiary.

In 2009, ATL began working on batteries geared towards EVs. This production strategy happened in the context of the emergence of broader state support for the Chinese EV industry, the first phase of which began in 2009 (as retroactively explained in the 12th Five-Year Plan issued in 2012). This state support was based around a subsidy-regime towards EVs first for public transportation but by 2010 also for private consumption – initially targeting a smaller number of cities. The subsidies gradually ratcheted up in amount and geographical coverage over the next few years along with support for the build-out of EV infrastructure. Simultaneously with the ramping up of state support for the EV-industry, in 2011 the state made technology-transfer to local companies a prerequisite for benefitting from the subsidies and eventually car buyers could only gain access to the subsidies if the battery was fully made by a Chinese company.10 Consequently, Zeng led a group of Chinese investors to “acquire an 85 percent stake in [TDK’s] nascent electric car battery business at the end of 2011”11, which was what became CATL (for current top-5 shareholders, see Table 1). By 2021 “cumulative state spending on the EV sector [has been estimated] at more than USD 125 billion.”12 These different initiatives taken together created a conducive environment for the development of local capitals around the EV-industry – herein battery producers like CATL.

| Shareholder name | Nature of shareholder | Ratio | Number of shares |

|---|---|---|---|

| Xiamen Ruiting Investment Co., Ltd. (wholly owned by Zeng Yuqun) | Domestic legal entity | 23.31% | 1,025,064,949 |

| Huang Shilin | Domestic natural person | 10.60% | 466,021,310 |

| Hong Kong Securities Clearing Company Limited | Overseas legal entity | 9.72% | 427,454,875 |

| Ningbo United Innovation New Energy Investment Management | Domestic legal entity | 6.46% | 284,220,608 |

| Li Ping | Domestic natural person | 4.58% | 201,510,277 |

Table 1 – Top-5 shareholders as of end of 2023 – the next 5 are each ~1% (Source: CATL website).

From the early 2010s CATL thus began to build up its different production sites in China. In the broader context of a facilitative state acting as “promoter” and “supervisor” to national capital, China became the world’s largest market for EVs in 2015.13 In the same year, the state launched its “Made in China 2025” strategy along with what became known as the “battery whitelist”. Where the former aimed to transform China into a global high-tech manufacturing powerhouse – including of EVs and their varied components – the battery whitelist announced the select number of Chinese companies that would receive subsidy support.14 Consequently, in these years, CATL experienced explosive growth and in 2018 the company went public through an Initial Public Offering on the Shenzhen Stock Exchange. Since then, its net profit margins have consistently been higher than its main lithium-ion battery making competitors (see Figure 3).

CATL’s rise happened through the company’s bet on a particular battery technology known as NMC (lithium nickel manganese cobalt oxide), which was the dominant battery in EVs initially.15 For the automotive sector, there are three categories relevant today: NMC, NCA (lithium nickel cobalt aluminium oxide) and LFP (lithium iron phosphate).16 Both NMC and NCA have a high nickel content and have until recently had higher energy density than their LFP-counterpart, which means a longer driving range for EVs. LFP, however, has lower costs of production so the different categories are also associated with different consumer market segments in the automotive sector. However, technological development – at the moment mainly concerning energy density and charging efficiency – is rapid and battery producers are under constant pressure to innovate and stay ahead or be wiped out by competitors. In China, LFP-based batteries – associated especially with CATL’s competitor BYD – already accounted for a larger part of the Chinese market in 2021 than NMC and are expected to become globally dominant by 2030 in most EV-markets.17 CATL has, however, also moved forward on the LFP front and in April 2024 launched the first LFP-battery with a range above 1000 km along with rapid charging abilities.18 Simultaneously, CATL is at the forefront of developing an entirely new battery chemistry different from the three mentioned above (all of which are forms of lithium-ion batteries): sodium-ion batteries. These were introduced commercially by CATL in 2021 and the company has since been building up a supply-chain around it. Alongside this, the Chinese state has announced the promotion of the sodium-ion battery industry in its 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-25) and CATL is thereby well-positioned to benefit from its historic relation with the state.19 Indeed, according to The Financial Times, in 2023 CATL was the largest receiver of state subsidies – receiving three times as much as its closest competitor, BYD.20

These different battery technologies have different resource requirements. Consequently, the pursuit of different battery technologies has different implications for the particular state-capital alliances that are useful for a company like CATL, who depend on resource-holding states for these vital inputs to their batteries. For resource-holding states hoping to facilitate capital accumulation within their territories in the energy transition, the evolution of different battery technologies is similarly crucial with, in some cases, entire national industrialization plans built up on a bet around the role of a particular resource in the EV-supply chains – e.g. nickel in Indonesia, as we discuss below.

A peek into CATL's global strategies

While CATL in its initial stages focused on gaining access to key resources internally in China – e.g. its focus on lithium in the Western part of the country – and was primarily geared towards catering to companies operating on the Chinese market, with the company’s expansion it is increasingly being driven to the world market both for natural resources and market share. CATL’s global strategies, as we discuss in this section, can thus be conceptualized in terms of dealing with imperatives around firstly, its production process, and secondly, around securing market share. The first imperative entails securing regularity and certainty of its supply of raw materials for its production process without interruption, while at the same time minimizing the costs associated with these raw materials. The point around costs is particularly crucial as raw materials amount to 60-70% of the total costs of battery cell manufacturing and hence stable and cheap supply become key parameters of competition between battery producers.21 For this reason, battery producers are attempting to manage these costs by creating different types of ties with actors directly engaged in extraction (meaning particular mining companies) and those facilitating extraction (meaning particular states). The second imperative concerns the constant battle to uphold and expand the company’s market share across the world, this of course to sell as many batteries as possible and hence make as much profit as possible. However, in the context of dwindling demand on the home-market in China and rising geopolitical tensions from the US and the EU, this imperative is presenting considerable challenges to CATL. Consequently, as we discuss in the second half of this section, it is trying to adapt around industry and trade policies that are increasingly hostile towards the involvement of Chinese actors in EV-supply chains in order to not lose access to EU and US-markets.

3.1 Strategies of raw material supply

Since early 2018, CATL has actively been developing different types of economic ties with companies and states outside of China in order to secure access to various ‘critical minerals’ that make up their raw materials for batteries. Most recently, CATL has entered a Joint Venture agreement with Bolivia's state-owned lithium company Yacimientos del Litio Bolivianos. This agreement gives CATL the rights to develop two lithium plants estimated to be able to yield "up to 25,000 metric tons of battery-grade lithium carbonate" meaning the company will effectively become directly engaged in mining activities.22 Beyond this direct involvement in lithium mining, the company has also made a series of equity-investments into other companies that are engaged in the mining of lithium in Australia and Canada and cobalt and lithium in the Democratic Republic of Congo (See Figure 4).

| Chinese battery players’ global chase | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Date | Critical mineral | Amount | Form of investment | Details |

| Contemporary Amperex Technology Co. Ltd. (CATL) | |||||

| Bolivia | June 2023 | Lithium | US$1.4 B | JV | JV agreement with Bolivian SOE Yacimientos de Litio Bolivianos on lithium mining and refinery. |

| Indonesia | April 2022 | Nickel | US$6 B | JV | JV agreement with Indonesian SOEs Industri Baterai Indonesia and Aneka Tambang on integrated battery supply chain. |

| China, Democratic Republic of Congo | September 2021 | Lithium | US$240 M | Minority interest | Suzhou CATH Energy Tech. Co. Ltd., a JV of Pei Zhenhua and CATL, acquired 24% of Manono lithium-tin project. |

| Democratic Republic of Congo | April 2021 | Cobalt | US$137.5 M | Minority interest | Acquiring 25% stakes in KFM Holding Ltd. |

| Canada | September 2020 | Lithium | C$8.6 M | Minority interest | Acquiring ~8% stakes of Neo Lithium Corp. |

| Australia | September 2019 | Lithium | A$55 M | Minority interest | Acquiring 8.5% stakes of Pilbara Minerals Ltd. |

| Canada, Morocco | April 2018 | Nickel, cobalt | C$15 M | Minority interest | Acquiring 25% of North American Nickel Inc., which operates in Canada and Morocco. |

| Canada | March 2018 | Lithium | NA | Acquisition | Acquiring controlling stakes in North American Lithium Inc. |

| As of June 2023. NA = not available; JV = joint venture; SOE = state-owned enterprise; M = million; B = billion. * Estimated. The above list is non-exhaustive. Source: Company announcements; media reports; S&P Global Ratings. © 2023 S&P Global. | |||||

While this global strategy of extraction for various resources that are relevant to all three currently dominant cathode chemistries should be kept in mind, we here zoom in on one of the above cases: Indonesia.

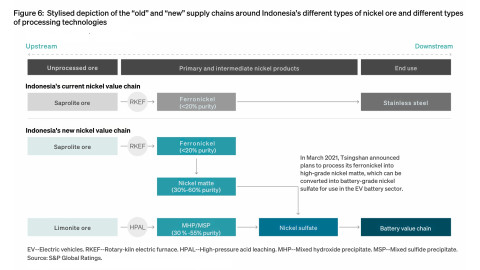

With its massive reserves of nickel, which are a key component in the NMC battery chemistry, Indonesia has taken central stage in the emergence of EV-supply chains in recent years (see Figure 5).23

Source: Standard & Poor's Financial Services LLC. All rights reserved. See: https://www.spglobal.com/ratings/en/research/articles/230313-the-promise-and-pitfalls-of-indonesia-s-nickel-boom-12632705

Pressing analytical and political questions

By way of conclusion to this initial scan of some of the global tapestry that is CATL's accumulation strategy, we want to raise a series of what we consider pressing analytical and political questions in the current 'Darwinian world'.

- Which challenges and opportunities does the increasing functional integration of the mining and automotive sector present for social movement struggles around the just transition? Are there opportunities for forming alliances among workers and activists along the supply chain? Do just transition proposals from e.g. automotive workers’ unions need to more seriously reckon with the struggles of mining-impacted populations and mine workers – and vice versa?

- How can and should movements position themselves in relation to changing state-capital alliances and to ‘green’ national industrialization processes? How does this positioning differ based on context, e.g. for states in the so-called global North or South? What are the specific implications in relation to critical minerals?

- To what extent is the neoliberal trade regime and broader model of globalisation as we have known it transforming amidst the rising geopolitical tensions and trends towards a deglobalization/slowbalization? And if it is transforming, who will benefit from these changes and what does this mean for social movement strategy?

- What are the possible risks of deglobalization along nationalist lines? What would an internationalist deglobalization look like? What kinds of economic, resource, trade and environmental policies could contribute to this?

- How should social movements approach the EU's and US's 'China-bashing' and is it at all possible for EU- and US-corporations to decouple from Chinese actors? Which challenges and opportunities do their attempts to do so open up for social movements?

- In terms of green industrial policy in the Global South, whether and how can regionally coordinated industrial policy re-structure mining governance to maximize local socio-economic benefits while minimizing environmental harm?