CATL, capitalist strategies and emerging state-capital alliances The case of CATL in Hungary

Topics

Regions

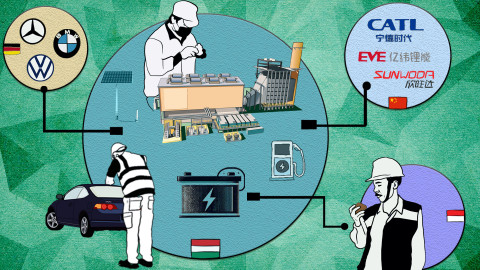

Chinese battery giant CATL’s decision to build a second European plant in Hungary underscores its commitment to the EU market, despite rising protectionism. Partnering with German carmakers relocating to Hungary, CATL benefits from lower labour costs and favourable energy arrangements, while Hungary’s government subsidises these ventures—driving rapid reindustrialization but shifting environmental and social costs onto taxpayers and workers.

Illustration by Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

Dependence on manufacturing FDI

One main element of this situation is Hungary’s long-term dependent relationship with German industry - particularly automakers. Like other semi-peripheral economies elsewhere and in the region, Hungary has long been struggling with the problem of technological dependence resulting in unfavorable terms of trade. Its model of state-socialist import substitution industrialization relied on technology imports from the West, balanced by re-exporting Soviet oil and raw materials. After the oil crisis of 1973 upset this balance, Hungary spun into a debt spiral, followed by the collapse of the socialist economy. As a result, Hungary was strongly dependent on Western capital during its reintegration into capitalist markets after 1990. After post-socialist deindustrialization created a vast pool of cheap labour, Hungary’s partial reindustrialization happened on lower positions of value chains dominated by Western companies. German carmakers’ outsourcing to Central Europe, including Hungary, happened in the context of the EU’s larger model of economic governance, where the common currency, strict competition policy, and relatively closed labor market helped German industry maintain its position despite declining profitability in the automotive sector. Cheap East European labor and Russian fossil energy were key pillars of this model. After the financial crisis of 2008, German producers stepped up their relocations to the East, to further cut costs. Hungary’s successive Orbán governments (in power since 2010) provided strong support to relocating companies, from direct subsidies and tax cuts to the transformation of Hungary’s labor law and education system. On the one hand, these measures helped boost Hungary’s exports, and thus helped to maintain a positive trade balance, at a time when the government was trying to reduce dependence on Western loans in order to gain maneuvering space for its economic policies that favored domestic capital groups. On the other hand, the same reliance on exports produced by German companies increased Hungary’s macro-economic dependence on them, and perpetuated the politics of favorable treatment necessary to attract further investments. . After 2022, this relation was deepened and extended to East Asian manufacturers, as new FDI became necessary to compensate for the increased need for external financing, after the EU withheld funds for rule of law violations, and the global liquidity crunch made alternative financing less available. The Orbán governments’ strong centralization of political power helped maintain the direction of economic policy favoring manufacturing investments, despite resistance by local labor and political constituencies – including the 2018 demonstrations against labor code changes that protesters called the ‘Slave Law’.

In the 2010’s, Hungary’s role as a manufacturing site for German automakers expanded in parallel with a turn in German industry’s export policies: after the EU single market could not provide enough compensation for declining profits after 2008, exports turned to global – primarily Chinese – markets. Meanwhile, as late adopters of the electromobility transition, German carmakers have been partnering up with East Asian, including Chinese, battery producers, to build their new Electric Vehicle (EV) models. The electromobility boom of the early 2020’s, combined with the effects of Russia’s war on Ukraine, and the global turn towards protectionist industrial policy has largely complicated this picture. First, Chinese manufacturers upgraded from being battery makers to becoming EV producers, squeezing out German producers from their positions in the Chinese market, and then stepping up as their competitors on global markets. Second, in the context of growing geopolitical and geoeconomic tensions, the EU’s reactions have been torn between a now diverging set of capitalist interests, contradictions also manifesting in the conflict between anti-Russia sanctions, the EU’s battery strategy’s (including the Critical Raw Minerals Act’s) aim to build independent supply chains, and German carmakers’ need for Chinese collaborations and Russian energy. Third, the loss of cheap Russian energy imports due to sanctions placed a vital blow on already struggling German industrial competitiveness. Hungary’s geopolitical balancing has so far made it a site where both Chinese inputs and Russian energy are available.

A second main element in Hungary’s current reindustrialization has been the interest of Chinese manufacturers in creating production sites within the EU, in the hope of bypassing protectionist policies and maintaining access to EU markets. This strategy does not only apply to suppliers to German automakers like CATL, EVE Power or Sunwoda, but also to EV producers. Similar to the strategic placement of its Mexico plant within the US-Canada-Mexico free trade zone, BYD, a Chinese EV producer, is building its first European plant in Hungary.

Building domestic capital

The third key element of Hungary’s new profile in the current global industrial restructuring is the attempt by the Hungarian regime to manage conditions of external dependence in a way that opens space for the capitalization of state-backed domestic companies. Since 2002, the current governing party Fidesz has been building ties with national capital groups disgruntled by Western capital’s dominance in the post-socialist era. Its victorious 2010 election campaign was done under the slogan “economic freedom fight”. After 2010, successive Orbán governments have made strong steps to diversify away from Western financing and its strict conditions for economic policy. Next to turning to global money markets (soared at that time by Western central banks’ quantitative easing), this included new deals with Russian and Chinese capital, which were at the time looking for entry points into the EU. Initially, these deals were primarily linked to large infrastructure projects – like the second unit of the Paks nuclear energy plant, built with Rosatom’s technology (another key resource for relocating German producers), or the Budapest-Belgrade railway, built as part of China’s BRI. These collaborations created conditions where Hungarian domestic capital could be made part of new financing deals.

While aided by favorable state treatment, the production of Hungarian state-backed capitalist “champions” has suffered from a limitation following from technological dependence: it could be done in domestic services, where new market shares could be obtained by state intervention, but it could not be achieved in export manufacturing sectors, where entry depended on technological competence. Thus, in the 2010’s, newly centralized state capacities have been used to produce new players in the field of domestic services like construction, transport, telecommunication or banking. Some of these became subsidiaries of new infrastructure projects, including in Paks II and the Budapest-Belgrade railway construction. In the current context of geoeconomic reorganization, this relation has been upscaled in several ways. The vast infrastructural needs of the new reindustrialization boom are served by state-funded projects (sometimes also using European funds), which provide state-backed companies new opportunities for expansion. Water, energy and transport systems around new industrial sites are being built by the post-2010 regime’s main state-backed construction firms – including Debrecen’s Southern Economic Zone, where CATL’s new plant is built. These collaborations do not only allow for the expansion of new, increasingly monopolized domestic service capacities, but also some technology purchases through joint ventures (like V-Híd’s recent collaboration with AZD Praha for railway signaling equipment), up to the level where these companies are attempting to step out on foreign markets (like Ganz-Mavag’s bid for the Spanish train manufacturer Talgo). At the same time, these companies do not enter EV producers' value chains as suppliers that may access technology and thus be the site of technological upgrading, as was the case in the collaboration between German carmakers and East Asian suppliers. While government communication often portrays reindustrialization as a path towards the country’s industrial upgrading, the fact that relocating companies do not bring research and development functions or establish collaborations that allow technology sharing suggests a lasting differentiation of roles between foreign manufacturing capital and Hungary’s new champions.

Support for manufacturing FDI

The Hungarian government’s massive support for foreign manufacturers like BMW or CATL needs to be understood in this context: it not only helps the producers who bring investments, but also the state-backed domestic companies who provide infrastructure services to them. On the one hand, government support includes elements that provide direct subsidies; this happens in the form of cash grants (for job creation) and tax cuts. On the other hand, it involves elements that reduce the costs of relocating production.

Direct subsidies and infrastructure-building

Next to direct cash grants and tax cuts, the main form of monetized support to new manufacturers is the construction and maintenance of necessary infrastructure paid by public funds. In the case of CATL, these elements amounted to 800 million euros – a generous condition that contributed to Hungary winning the competition with Poland and Serbia for becoming CATL’s new location (g7.hu, 2024).

Public funds for infrastructure-building include central state funds as well as local government funds, the latter sometimes being obliged to construct new infrastructural services. EU funds for infrastructure building are also channeled into these projects. Next to new transport infrastructure (road, railway, and logistical nodes), the expansion of existing water and energy networks is a key necessity, as the energy and water needs of new factories exceed the capacity of current systems. In the case of Debrecen, public funds allocated for the Southern Economic Zone’s infrastructural development amounted to more than 300 million euros without the costs of water works. The expense of new energy and water systems has further public cost aspects. It is not clear whether the system-level updates to public service companies that are necessitated by the inclusion of new super-consumers will be compensated by further state funds. If not, costs may be passed on to end consumers. In the case of water, this problem is aggravated by the issue of desertification, which has become a problem in several areas due to climate change and inadequate water management techniques. In the case of energy, state investments into updates of the public grid (around 100 million euros yearly) are driven by industry needs. Although the share of solar energy has been considerably growing in the last years (5.6 GW by 2023, with Hungary’s commitment by 2030 being 12 Gw), continued reliance on Russian fossil fuels, new fossil deals with foreign suppliers, the use of coal to compensate for volatility caused by solar, and the prioritization of industrial needs in grid development suggest conflicts with Just Transition aims. While the public foots the bill, state-backed domestic service companies capitalize on lucrative contracts in these infrastructure projects, many of which end up adding extra costs before they are finalized.

Energy, land and water

Beyond infrastructure-building, measures that reduce production costs also include securing access to cheap energy, land, water, and favorable labor and environmental regulation. In the field of energy, maintaining the flow of Russian oil and gas, and expanding the Paks II nuclear plant are essential parts of the package offered by the government. Such, too, are its new efforts to diversify the sources of fossil energy, as well as its support for new solar plant projects (the latter are also built by Chinese investors themselves as they expect energy needs to surpass existing supply even with these efforts at expansion).

Water and land are provided by favorable regulation and management of procurements, including the creation of a centralized system of Special Economic Zones in cases where local governments resisted the creation of new industrial sites due to pressure from local inhabitants and farmers voicing land- and water-related concerns. While the Southern Economic Zone of Debrecen is not a SEZ, the first public hearings related to CATL’s investment were highly contentious in this case, too. At the moment, public hearings have been reduced to an online format where citizens cannot actively disturb the process.

Beyond water and land use, the environmental effects of battery production mainly include toxic waste resulting from chemical production processes, which can affect land, water and air in and around the factories. Next to easing already lax regulation, favorable regulation in this field includes reducing the capacity for control and enforcement. In the case of already functional battery factories, there is no publicly available information on toxic waste regulation, and environmental impact studies are often not made public. Putting public hearings online further reduces citizens’ opportunities to ask for reliable information. Environmental fees, when companies are made to pay them, are minuscule compared to locally made profits, or even the state support given to manufacturers. Since 2023, companies that are proven to break environmental regulation are allowed to pursue the process of rectifying practice without being closed down, or even paying a fee.

A new labor regime

When it comes to labor regulation, one main element of government policies has been to further relax the system of working time remuneration. The first big step in this direction has been the “Slave Law” of 2018, which pandered to the needs of German producers to make labor follow the timing of production cycles as closely as possible, without extra costs. This law was further modified in 2020, allowing for an employment model resembling Foxconn’s factories in China. This is a labor regime characterized by low-paid, low-skilled and extremely flexibilized labor employed with severely degraded working conditions, and made constantly available for flexible labor times through a dorm system located close to production sites. This regime has been developed to serve the maximal use of domestic migrant labor in the case of China’s electronic industry, where repressed prices were the condition of growth and technological upgrading in light of global competition. With the electronic transition of the auto industry in the context of a global profitability crisis, this employment model has been spreading to car manufacturing, too (Lüthje, 2019). In the case of Hungary’s reindustrialization, the labor migration aspect of the model is becoming highly relevant as its own labor pool has been already exhausted by the industrial relocations of the 2010s. Since 2015, the government has encouraged the employment of regional migrant labor, a solution that has also met its limits, partly due to the war in Ukraine. Today, in the context of an extreme labor shortage, producers moving to the country plan to at least partly rely on migrant labor.

To serve this need, the government allowed temporary work agencies to bring in workers from neighboring non-EU countries and Central and South-East Asia, for short-term labor contracts. This measure was further formalized with the 2024 modification of the immigration law, which eased visa processes for temporary work migration, while also applying strict limitations. Guest worker visas are given for fixed terms, and do not allow for family unification or settlement. These measures are emphasized by the government when it receives criticism for not being consistent with its decade-long anti-migration rhetoric. At the same time, keeping workers’ families abroad and not allowing them to settle down in Hungary guarantees the conditions of migrant work that is inherent to the Foxconn model. As workers are spending time away from their families, they focus on making as much money as shortly as possible, which ideally fits the system of workers’ dorms and flexibilized labor time, and exempts the employer from most other costs of workers’ reproduction. Since the jobs created by battery manufacturing in Hungary are typically low-skilled, relatively high labor fluctuation does not pose a problem for employers. During contract time, workers are incentivized to contribute maximally to the flexibilized system of labor time by a framework where guaranteed basis income remains below living costs. The rest of the income is given in the form of bonuses regulated at the company level. Depending on regulation, bonuses can be canceled in the case of underperformance of departments, or in case someone falls sick and misses a few workdays. Dependence on bonuses, and thus on performance evaluations, incentivises workers to accept harsher treatment, overtime work, or work while sick.

Another main aspect of labor regulation favorable to companies regards workplace safety, which is becoming increasingly relevant as an industry with sensitive chemical processes is hiking up production in the country. Industry-specific measures of work protection are hindered by the reduction of the institutional system of work protection, the existing system’s lack of knowledge on new battery manufacturing technologies, lack of capacity on the side of work protection control, increasingly lax regulations, as well as the centralization of work protection functions into politically controlled government offices.

Trade unions have been struggling to keep up with challenges born from new developments. The progressive dismantling of the system of social dialogue since 2011 significantly reduced their voice. Since 2010, labor rights have been dropped from the list of conditions for direct state support for relocating companies. Unlike German companies which brought with them some standards of German trade union models when they relocated, East Asian battery makers are often anti-union. While greenfield projects require new capacities to build local unions from scratch, this capacity is seldom available within existing trade union structures. Meanwhile, the employment of migrant workers through temp companies creates a fragmentation among workers’ situations, where it is increasingly hard to find common platforms for union-level representation. Despite these drawbacks, Hungarian unions have been making steps to include newly arriving workers.

Conclusion

The location of CATL’s second European plant within Hungary is a strategic move that primarily serves to maintain access to EU markets, including its European automotive partners, despite protectionist policies. Within Hungary, CATL will collaborate with German carmakers who have been moving their capacities into the country – first to cut labor costs, and recently also to access Russian energy and Chinese suppliers. Hungary’s generous state support to both German carmakers and battery-makers like CATL is producing a historic wave of reindustrialization in the country. On the regime’s side, this serves to cover the increased need for external financing (while avoiding loans with strict policy conditions), as well as to enable the expansion of state-backed domestic capital as service providers to new manufacturers. These collaborations typically do not include technology sharing that would allow for domestic capital’s industrial upgrading. State support for foreign companies includes direct subsidies, and measures that reduce costs: infrastructure-building, provision of cheap energy, land and water, and favorable labor and environmental regulation. The costs of these measures are largely externalized to taxpayers, domestic and migrant labor, and the environment.

References

Czirfusz, M. and Szabó, L. (2022) Regional risk assesment. The electronics industry in Hungary. Amsterdam: Electronics Watch. Accessed https://electronicswatch.org/regional-risk-assessment-electronics-industry-hungary-november-2022_2615914.pdf, 30-04-2024.

Czirfusz, M. (2023). The battery boom in Hungary: Companies of the value chain, Outlook for workers and trade unions. Budapest: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung. Accessed https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/budapest/20101.pdf, 30-04-2024.

g7.hu (2024). 64 millió forintba kerül egy akkumulátorgyári munkahely a magyar állam számára. G7.hu, 20-03-2024. Accessed https://g7.hu/vallalat/20230320/64-millio-forintba-kerul-egy-akkumulatorgyari-munkahely-a-magyar-allam-szamara/, 30-04-2024.

Gagyi, A., Gerőcs, T. and Szabó, L. (2024) New bridge model: Hungary’s reindustrialization in the era of Chinese technology export and the global industrial policy turn. Fordulat 33(1), in print.

Gerőcs, T. And Gagyi, A. (2023) Global crisis and the realignment of Eastern European capitalist class alliances. In dos Santos, F.L.B., Gerőcs, T. And Lero, C. (eds.) The radical right: Politics of hate at the margins of global capital. Brill.

Merk, J., González, A. and Czirfusz, M. (2024). Electric dreams, hard realities: What the battery boom means for workers in Hungary. SOMO. Accessed https://www.somo.nl/electric-dreams-hard-realities/, 05-11-2024.

Szabó, L. (2024) Monitoring partner profile: Periféria Policy and Research Center, Hungary. Amsterdam: Electronics Watch. Accessed https://electronicswatch.org/en/monitoring-partner-profile-perif%C3%A9ria-policy-and-research-center-hungary_2643683, 30-04-2024.