The Arakan Army's Struggle for Regional Sovereignty Imagining A New Future Union

Regions

The devastating earthquake which struck Myanmar last week has brought international attention to the civil war and national breakdown in the country at a critical time. The humanitarian emergency is severe, and temporary ceasefires have been called. But distrust of the SAC regime runs deep and popular resistance is determined. In this commentary, Naing Lin analyses the continuing advances made by the Arakan Army and its allies, with the AA now the de facto government in most of Rakhine State. As he asks, could new political models of autonomy and ethnic self-governance be evolving?

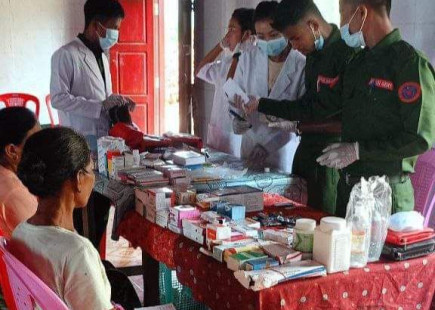

Photo credit Border News Agency (BNA)

Although the recent deadly earthquake, with a magnitude of 7.7 and centred near the towns of Sagaing and Mandalay in central Myanmar, was a natural disaster, the country’s ongoing political crisis will inevitably and unfortunately exacerbate the tragedy’s negative consequences. The early death toll, as confirmed by some credible sources on 3 April 2025, exceeds 2,000, and this figure is highly likely to rise in the coming days. Despite the National Unity Government (NUG), a key opposition group, announcing a two-week unilateral ceasefire on 29 March, armed clashes still erupted in several locations, accompanied by continued junta airstrikes.

Additionally on 1 April, the Three Brotherhood Alliance (3 BHA), which consists of the key ethnic armed forces of the Arakan Army (AA), Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA) and Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), released a joint statement announcing the cessation of a 30-day military offensive in their areas. The following day on 2 April, both the military regime of the State Administration Council (SAC) and the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) declared 22-day ceasefires.

Armed clashes and airstrikes, however, reportedly persisted in Bhamo, Indaw and Waignmaw townships of Kachin State as of 3 April. Some observers therefore criticized the SAC’s temporary ceasefire as a superficial gesture, suggesting it was primarily intended to portray themselves as ‘good guys’ to the international community by aligning with the BIMSTEC meeting held in Bangkok from 2-4 April. Notably, too, the SAC’s statement explicitly stated that they would continue attacks against opposition groups if the latter persist with ‘recruitments’ in their areas. This implies that the SAC could strike opposition groups at any time under the pretext of alleging ‘recruitments’, which the opposition typically conducts – as does the Myanmar military – during ceasefire periods.

Hopes were thus very fragile that the earthquake disaster would bring about a change in SAC policy. While many well-intentioned diplomats and observers hope for a political turning point similar to the 2004 Aceh resolution that could end the armed conflict, Myanmar’s future remains far more complex and highly uncertain.

One critical aspect of this nationwide fragility is the current situation in Arakan, located in western Myanmar. The last resumption of war on 13 November 2023 between the SAC regime and Arakan Army, led by the United League of Arakan (ULA), has brought an unprecedented degree of change that is unlikely to be reversed in any major way. The basic changes include the transformation of the security and military order under the AA and the political and administrative structures headed by the ULA and its governmental body, the Arakan People’s Revolutionary Government (APRG). Out of the 18 townships on the Arakan military front, 15 are now under the control of the AA (including Paletwa demarcated in Chin State). The other three townships include Sittway, capital of the SAC’s Rakhine State government; Kyaukpyu, the second capital and economic host of critical Chinese investments; and Manaung, an isolated island near Kyaukpyu with geopolitical value for controlling the Arakan coast and sea.

The nature of the battles which the AA has experienced in Arakan is different from other areas of the country as it has faced all three land, air and navy forces of the SAC. The military losses by the junta during the past year have been huge. These include one regional military command centre in Ann, three military operation commands in Kyauktaw, Buthidaung, and Taungup, 35 light infantry battalions (LIBs, Kha-Ma-Ra) and infantry battalions (IBs, Kha-La-Ra), three artillery battalions and ten border guard police regiments as well as the newly-reinforced troops from divisions 11, 22, 55, 77, 88, 99, 101 and MOC-10. The evidence is clear. The SAC military – known as the Sit-Tat (Tatmadaw) – has become an isolated and lonely force in nearly all the townships of Arakan where AA troops stood tactically, numerically and logistically in superior positions, apart from the battlefields in northern townships, such as Buthidaung and Maungdaw, where Rohingya groups and recruits joined the fight against the AA.

Among the losses that the SAC has experienced, the importance of the advanced military equipment which the AA has been able to seize should not be underestimated. For example, open source media have highlighted that the AA now possesses Chinese-made WMA-301 Tank Destroyers, Ukrainian MT-LBMSh vehicles, M101 howitzers, 105 mm M56 howitzers and D-30M howitzers. This strongly suggests that the current military victory of the AA could not have been achieved as quickly as possible without such newly-captured equipment and weaponry. It highlights that the military equipment and supplies captured by the AA in the Paletwa battle were followed by those seized in Kyauktaw, Mrauk-U, Minbya and Pauktaw, and then used again for attacking the junta’s headquarters in Buthidaung, Ann, Taungup and other townships. This was confirmed by the AA’s propaganda release on 26 December 2024 about the capture of the Sit-Tat’s Western Regional Command which stated: ‘The enemy’s weapon is our weapon.’

In contrast, the current battlefields where the AA is operating in Sittway and Kyaukpyu are amphibious and geographically-different from previous terrain, and it is an unknown factor for the present to what extent the existing weaponry could be useful. These two towns have similar geographies and logistical characteristics. First, both have riverbanks that connect with the seashores, making it more difficult for the AA to lay siege from all directions given the SAC’s superior aerial and navy powers. Second, both have seaports and airports meaning that the SAC can seek to continue logistical support during a time of war. And third, with Sittway harbouring Indian investments and Kyaukpyu hosting Chinese, it means that geopolitical factors should not be excluded in assessing the course of warfare on these fronts. Given intensive Chinese political and diplomatic pressures around Kyaukpyu, Sittway may be a more war-prone target for both the AA and SAC.

Beyond Arakan, the impact of the ongoing battles on the eastern belt of the Arakan Yoma highlands between the SAC and AA, including allied actors, should not be overlooked. Both sides consider that this has ‘existential’ meaning if the SAC loses, with huge implications for the security of defence materials and manufacturing industries on the western side of the Ayeyarwady river. On the other hand, if the result is otherwise, it could also mean that the southern towns of Ann, Taungup and Thandwe under AA control could be subjected to direct threat from the SAC. In consequence, the wars both inside and outside of Arakan could have significant impact on the nationwide military pendulum between the SAC and anti-SAC forces.

Institutional and ideological development of the ULA

Beyond the military dimensions, another arena that observers should not miss in analysing the ULA/AA movement is the ideological and institutional development of the organisation and cause itself. Founded in 2009 in Kachin State, the AA appeared to have little hope of immediate advancement in the China borderlands at that time where there were ceasefires with different ethnic armed organisations and national politics were about to turn into an era of so-called ‘democratic’ transition. It meant that AA founders faced an ‘anti-armed struggle’ environment which was gaining traction under the guise of a new ethnic ‘peace process’ initiated by the quasi-civilian government of President Thein Sein who came to office in 2011.

The return of war, however, in Kachin State in mid-2011, when the Sit-Tat launched military operations, was followed by the subsequent resumption of conflict in neighbouring Ta’ang and Kokang territories during 2011-15, adding more strategic value to the AA’s presence in the frontier zones. Other events sustained the momentum. Causal factors included the outbreak of communal violence in Rakhine State in 2012 and the increasing migration of young people to the Hpakant jade mining region of Kachin State and along the China border. Such insecurity and alienation among young people supported the political mobilisation of the ethnic Rakhine population, providing more than necessary human resources for the AA movement.

By 2015 the AA was already a relatively well-trained and well-armed group with an estimated strength of 2,500-3,000 fighters. Certainly, the AA was much more representative and powerful than the veteran organisation of the Arakan Liberation Party/Army, an earlier Rakhine armed movement, which was promoted and encouraged by the government to be a signatory to the so-called ‘Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement’ (NCA) in October 2015. There is no turning back history. But the question can still be asked: ‘Would there have been an alternative outcome and fate for the AA if it had been allowed to become a signatory to the NCA?’

From this point, as many analysts have pointed out, the critical factor that has brought the AA’s development to its current status is the movement’s comprehensive and systematic progress in alliance formation. Collaboration already existed, but in December 2016 the AA formally entered into the Northern Alliance (NA) with the Kachin Independence Army, (Kokang) Myanmar National Defence Alliance Army and Ta’ang National Liberation Army in northern Shan State. They similarly had been excluded or unwilling to sign the NCA which they believed, rather than being a peace process for political reform, was being used by the government as a divisive stratagem to try and roll out Sit-Tat control. Five months later in April 2017, the AA entered into another grand political and diplomatic formation, the Federal Political Negotiation and Consultative Committee (FPNCC), in which the AA and other NA members formally participated with three more powerful ethnic armed organisations, the United Wa State Army, (Mongla) National Democratic Alliance Army and Shan State Progress Party, which have ceasefires with the government.

In many respects, the FPNCC is a political and solidarity front among EAOs that did not approve of the NCA. It was thus the famous Three Brotherhood Alliance, established in June 2019 with the MNDAA and TNLA and four years later staged the ‘1027 Operation’ in northern Shan State, which consolidated the AA’s rise to become a more collaborative and battle-experienced force. In the meantime, from 2018 increasing confrontation had begun with the Myanmar military in the Arakan homeland following the entry of more troops and, when a de facto ceasefire was introduced in late 2020, the AA’s total troop was estimated to be between 10,000 and 15,000 fighters.

In conjunction with alliance formation and increasing manpower, the AA was also making progress on the ideological front. In the first-ever recorded speech by the AA leader General Twan Mrat Naing on 10 April 2014 on the movement’s 5th Anniversary, he announced the ‘Way of Rakhita’ (WOR) philosophy which will guide the group’s military, political and diplomatic strategy in the complicated field of Myanmar politics. Two years later in January 2016, the AA formed its political wing, the United League of Arakan, with the aim of providing political leadership and representation over the armed struggle.

From this point, the AA stepped up military operations in the mountainous areas of north Arakan against the Myanmar military. Then in July 2019, during a time of intense confrontations, the ULA/AA leader Twan Mrat Naing elaborated more to the people about the political slogan of the ‘Arakan Dream’. Many understood it to be a call for the rejuvenation of the once glorious Arakan Empire during the Mrauk-U period in the 16th and 17th centuries. As he explained: ‘Every Arakanese has a dream in their hearts. One day they should become a free citizen of their fatherland.’

At the time, however, the ULA leadership understood that they could not reach the ultimate goal in one advance. Thus, with the Sit-Tat leadership preparing for the military coup in early 2021, a de facto ceasefire in Arakan was agreed as a temporary solution in political equilibrium. In fact, the ceasefire would not last for more than two years, with a short breakdown between August and November 2022. But the ceasefire did mean that the ULA/AA now had enough time to prepare for another round of warfare and, equally critical, to establish administrative and judiciary footholds in its control areas, especially in rural districts in central and north Arakan.

During this time, the ULA leadership increased and extended its administrative build-up under a new governmental body, first called the ‘Arakan People’s Authority’ (APA) established in 2019 and later changed into the ‘Arakan People’s Revolutionary Government’. Throughout these years, the APRG gained increasing experience and outreach in general administration, taxation, land, judiciary and humanitarian affairs, including public management during times of emergency, including Covid-19 and Cyclone Mocha.

Today the challenges are on much larger scale after the capture of 15 townships covering 90 per cent of all territories and 80 per cent of the population. On a daily basis, the ULA must address the practical questions of managing public affairs in a range of issues from security, justice and humanitarian support to providing electricity, urban governance, municipal, internet and telecommunication services. At the same time, intense military confrontation continues with the SAC. With blockages on trade, transport and travel, the ULA-APRG experiences greater challenges than would occur in normal times in delivering all these vital services.

For these reasons, when looking at the situation today, it is important to remember that Arakan is a warzone with frequent junta airstrikes and artillery shelling, often targeting civilian populations. Meanwhile ULA/AA leaders still prioritise military and security tasks as their key agenda in tandem with political development and administrative build-up.

Photo credit Border News Agency (BNA)

Putting the ULA/AA in power versus responsibility matrix

The growing power of the ULA/AA movement in Arakan and neighbouring areas means that the ULA leadership and its governmental bodies have a greater responsibility over the population under their control. If power is defined as the ability to make things happen, responsibility should be defined as using that power in a way that benefits the residents of that territory or land. Therefore it is legitimate to ask in whose interests this power is being used.

First, however, it is important to recognise that the growing power of the ULA/AA for the moment is purely military. And second, the governing body of the APRG is still unable to fully replace or newly build governmental apparatus for essential public services, such as healthcare and education, due to the SAC’s all-out blockades of Arakan and the limited resources and time.

Added to this, discussions about the responsibility of government are always accompanied with the duty for the protection and provision of rights for the residents of that territory. In political philosophy, there are generally two sets of rights: ‘negative rights’ that demand freedom from government intervention in such areas as freedom of speech, freedom of movement, the right to privacy and property, freedom of religion and the right to legal due process; and ‘positive rights’ that ask for government provision in such areas as food and water, public and community safety, healthcare, education, housing and broader social security concerns.

In looking at these issues, it is possible to argue at the moment that the ULA’s performance and activities in these two sets of rights are mixed, and that political complexity continues in the security-military landscape. On the bright side, ULA authority has increased community protection and public safety. There has been a reduction in robbery, theft and gang violence among the general population, the return of property to original owners, and increased freedom of religion, culture and movement, especially for those Rohingya Muslims who had been locked down under previous Nay Pyi Taw governments and the Christian Khumi community in Paletwa township.

On the dark side, however, the ULA has often restricted critical speeches. The administration has been unable to meet increasing humanitarian demand and deliver essential public services in areas such as healthcare and education for the whole population. And the movement has been accused of nationalising the property of Rohingya individuals who collaborated with SAC forces and allied armed groups, notably the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, Rohingya Solidarity Organisation and Arakan Rohingya Army, in Buthidaung and Maungdaw townships. Later, the ULA also nationalized property of Rakhine businessmen on account of supporting the junta.

Added to this, there are also other controversial issues that need to be considered in exploring the protection and provision of rights under the ULA government. First, there is the question of recruitment into military service. Generally, many analysts in the past had considered the AA as having more than enough manpower for the voluntary recruitment of troops, especially from the ethnic Rakhine community. Rather, it was considered that the key challenge for the AA is that of armed power, weapons and ammunition. But after capturing extensive military equipment and land, the ULA/AA is now experiencing the rapid demand for more manpower to guard around 40,000 square kilometres of territory stretching from the international borders with India and Bangladesh in the north to the southernmost tip of the Arakan Yoma in Ayeyarwady Region.

Equally important, with continuing (and arguably increasing) threats from both the SAC and Rohingya armed groups, it is thought that the AA needs to arm more than 50,000 troops in total. The ULA leadership thus seems to think that both voluntary and mandatory recruitment is required from not just the ethnic Rakhine population but also other nationality groups in the territory to share the military burden while enjoying equal rights and freedom from the regime. Responsibilities, in essence, should belong to all communities. This, in turn, leads to a tension between the rights of citizens to be free from military recruitment and the duty to participate in national defence during times of emergency. Such is the challenge now.

A second controversial issue is that of ‘information security’. The media have reported that the ULA authority has used this justification and the risk of air strikes by the regime to deactivate telecommunications and internet access under its administered areas, providing limited internet access via its control devices under ‘starlinks’. In response, some people have argued that this is a violation of the right to digital information and communication as well as expression in digital space for the general population. The ULA, however, and many local people still think that this is the right decision: to try and block junta-controlled telecom networks since security information can easily leak, making the population more prone to targeted air strikes. In this case, ‘security’ prevails over ‘rights’ to information during wartime.

The alliance formation of the AA

A critical philosophical change appeared to occur in the ULA leadership with the movement’s growing military strength and territorial control after ‘1027 Operation’ in October 2023. This has been expressed in the readjustment of its approaches toward the landscape of current Myanmar politics. In an interview with the BBC Burmese on 2 February 2024, the ULA chief Gen. Twan Mrat Naing explained:

‘At first, we started to mobilize the Way of Rakhita in line with the Arakan Dream inspired by the Arakanese people. But later, more pragmatically, we came to understand that we need to consider the situation in other parts of the country for the liberation of all ethnic groups from the military dictatorship.’

Since this time, this change in approach has proven more than political rhetoric and has been confirmed by practical actions.

As a foundational step, all of the AA’s first chain of alliances, notably the KIA, MNDAA and TNLA, have now achieved unprecedented military victories over the past two years, coupled with build-ups in self-administration in Kachin and northern Shan States. The ULA/AA has thus moved on to adopting a second chain of alliances or partners closer to its homeland of Arakan. These organisations are newly-emerged armed groups, including the Chin Brotherhood (CB), People Revolutionary Alliance (PRA), Student Armed Force (SAF) comprising former university students from Yangon, Asho Chin Defence Force (ACDF) and Burma People’s Liberation Army.

Based on geographic proximity, it can be noted that, among the six members of the CB, there are four based in southern Chin State and two in northern Chin State. The four groups that are located in the south have control now from the Mizoram border of India to Magway border in the east: Maraland Defence Force (MDF), Chinland Defence Force-Matupi (CDF-Matupi, Brigade-1), Chin National Council/Chinland Defence Force-Mindat (CNC/CDF-Mindat), and Chinland Defence Force-Kanpetlet (CDF-Kanpetlet). Meanwhile the two forces in the north dominate mainly in Falam and Tedim townships, which are close to the lower parts of Sagaing Region where AA forces also participate in the fighting: the Chin National Organization/Chin National Defence Force (CNO/CNDF), and the Zomi Federal Union/People’s Defence Force-Zoland (ZFU/PDF-Zoland),

In these endeavours, the AA’s partners of the PRA-Magway, SAF and ACDF are of critical importance in military-security collaboration along the eastern belt of the Arakan Yoma down to the Ayeyarwady delta. While the CB in southern territories has now successfully taken control of all towns in these areas, the AA’s military collaboration with allies in the three critical regions of Magway, Bago and Ayeyarwady is an ongoing task that aims to clear out all regime forces from the eastern areas of the Arakan Yoma. This also means that up to 16 of junta’s key 35 defence manufacturing industries on the western of the Ayeyarwady river are under threat, which will have greater nationwide implications for the SAC’s firepower capacity.

For these reasons, the AA’s alliance formation between its first and second chains is different. In essence, while the AA’s first chain of alliances is critical in shaping nationwide politics, the second chain could be critical in regionwide political dynamics along the Chin Hills and Arakan Yoma where both the AA and its allies need each other for longer-term military and security coordination. But unlike the first chain, being a primary supplier of arms, trainings and technical support in the region, the second chain of AA alliances and territories could be described as an ‘AA-led security sphere’ or ‘AA-led power centre’ on the west of the Ayeyarwady river, southern Chin hills and broader Arakan region. Whether, however, all these new armed groups in the second chain of alliances will join the ULA’s political vision beyond their current military cooperation is an interesting question to be watched for in the future.

Imagining a new future of the union

On the surface, the current military and political landscape in Myanmar appears as one of anarchy, and this is occurring in a multi-power world with no higher centralised authority to provide security and stability in the country. Both the SAC and rival National Unity Government have claimed to be the ‘only centralised and legitimate’ governments in the country but both fall short of the minimum acceptable levels of representation or control to become the recognised government. While the SAC is more administratively centralized and militarily powerful than the NUG, the latter is more legitimate in the eyes of the people because of its inclusion of political, ethnic and civil society actors but it is also less centralized. In addition, it needs to be acknowledged that the effective controllers and administrators in much of the country on the ground are also non-SAC and non-NUG actors, many of which are nationality-based such as the AA, KIA, MNDAA and TNLA in this analysis, and they also do not claim to be the ‘government of the country’.

This, in turn, is setting up a series of dilemmas for the international community as much as the people in the country. With large sections of the international boundaries under the control of non-SAC and non-NUG actors, neighbouring governments are being pushed to deal with the existing actors, regardless of the political needs of Myanmar or the longer-term political implications. In the case of Arakan, both the Bangladesh and India authorities from local and central levels are inter-acting semi-formally with the ULA.

In terms of legitimacy, they have now granted political or de facto recognition to the ULA as the authority in Arakan on their borders even if they are not ready to provide diplomatic and legal recognition. But the needs for discussion and mutual exchange are urgent. In addition to the political issues, there is day-to-day collaboration along the borders in issues like trade, immigration, security, illicit narcotics control and health. In some respects, similar situations exist along the border for other ethnic movements controlling the borders neighbouring China and Thailand.

Cumulatively, the consequences are significant, reflecting that the SAC is under increasing military pressure in its own heartland while the security and political landscape cannot be reversed into the pre-2011 landscape when Myanmar military regimes dominated central government. Nor can the political stage be backed into the pre-2021 order when quasi-civilian and quasi-democratic administrations acted as constitutional governments backed by the Myanmar military. Instead, political understandings have to be moved forward and accommodate the growing multi-polar powers, many of them nationality-based, across the country and in the border regions. But this does not mean that solutions are impossible. With no political or peace settlements in sight, rather than the current failure of the ‘Republic of the Union’, all should be ready to imagine the future ‘Union of the Republics’ for the sake of longer-term security and stability.

* Naing Lin is a freelance political analyst and researcher writing about peace, democracy and community relations in Rakhine State, Myanmar.