Out-Organise the Enemy! Eqbal Ahmad and the liberation of Palestine

The late Pakistani intellectual Iqbal Ahmed did not oppose armed struggle. Far from it, he understood it as necessary under certain conditions, as in the case of occupied Palestine in its struggle against Zionist settler-colonialism. He thought, however, that it is important to subordinate armed struggle to a broader range of revolutionary politics, so it does not become arbitrary or random in choosing its targets. He understood it as a tool for mobilizing more political support, not for repelling/alienating potential allies. He thought that efficient resistance needs a flexible strategy that mixes as needed different militant and political tactics, based on the position the enemy occupies and the broader political context. He criticized positions that consider violence and nonviolence mutually exclusive strategies standing in a binary opposition, where one needs to choose this or that. In this sense, Ahmed’s analysis of political violence stands on a different ground from the purely normative/moralistic grounds on which some recent leftist condemnations of Hamas’s violence were based.

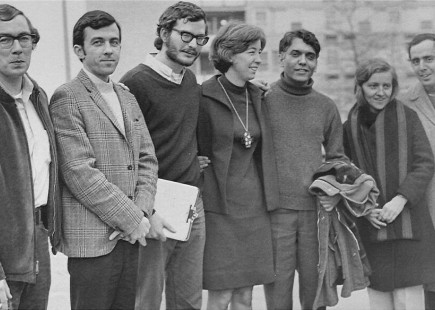

The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) was destined to fail as a liberation movement. That was the grim message Eqbal Ahmad delivered in December 1969 to a stunned audience of 300 Arab-American activists. The occasion was the annual convention of the Association of Arab-American University Graduates (AAUG) in Detroit, the first significant gathering in the United States to discuss the Palestinian freedom movement. Two years earlier, the Israeli military had occupied Gaza, the Sinai Peninsula, the Golan Heights and the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, overpowering the Egyptian, Jordanian and Syrian armies. Arabs in the US were in a state of anguish and isolation, as they watched Americans’ gleeful support for Israel, and became viscerally aware of an accompanying anti-Arab racism – including violent attacks. The AAUG was formed in this moment of despair; its aim was to consolidate an Arab-American movement that could promote the Palestinian cause to the US public.1

By the time of the 1969 convention, despair had given way to optimism. A new path for the Palestinian movement seemed to be emerging. The military defeat of the Arab states in 1967 had ironically cleared the way for Palestinian guerrilla groups like Fateh to come to the fore. The PLO, which until then had been an appendage of Egyptian foreign policy, came under the influence of these groups; Fateh’s Yasser Arafat became its leader. The new hope was that a guerrilla war could free Palestine, as Algeria’s National Liberation Front (FLN) had freed the country from French colonialism, and as the Vietnamese had done, first expelling the French and then prevailing even against the US war machine. Like most Arabs, the delegates at the 1969 AAUG meeting had adopted this view. Their expectations had been raised in March 1968 when, in the small Jordanian town of Karameh, PLO fighters held off a heavily armed and mechanised force of 15,000 Israeli troops. ‘The Palestinian is no longer refugee number so and so’, announced Arafat after the battle, ‘but the member of a people who hold the reins of their own destiny and are in a position to determine their own future’.2

Eqbal Ahmad took a different view. A military confrontation with Israel, he argued, was unlikely by itself to achieve justice for the Palestinians. Revolutionary violence was sometimes necessary, but most national liberation movements, he pointed out, did not adopt a theory of armed struggle as their entire strategy; rather they saw it as a tool that could advance their cause as part of a broader confrontation with the structures of colonial rule. The accent, Ahmad said, should be on the political aspects of the struggle – efforts to ‘bring into full relief the basic contradictions of Israel before the Israeli people and the world’. He advocated that Palestinians ‘ambush the enemy politically, administratively, and diplomatically, not merely militarily. … Every revolutionary struggle aims to isolate the incumbent morally – not just in the eyes of your own people, but in the eyes of the incumbent’s constituency and the world at large’. As he wrote later, the AAUG speech ‘shocked the audience with dire warnings’ that ‘Al-Fatah and other armed Palestinian parties were radical but wrong’. The Palestinian scholar and activist Ibrahim Abu-Lughod, one of the event’s organisers, recalled that it was a ‘beautifully crafted’ speech that established Ahmad as the most important public speaker for the Palestinian cause in the US, especially among the younger generation.3

In the audience that day was Fayez Sayegh, an Arab diplomat and intellectual, founder of the Palestine Research Center in Beirut and the person US media outlets called on the rare occasions they felt the need to drop a pro-Palestinian voice into the sea of pro-Israeli hegemony. He responded to Ahmad’s speech by defending a military strategy. ‘Karameh’, he said, ‘has changed our image from the fleeing Arab to the fighting Arab. There is no other way’. There were two streams to Palestinian self-assertion, he believed: military and diplomatic. Palestinian military successes would eventually force a settlement to be negotiated with the diplomats of the major powers; winning wider public support for the Palestinians was at most a marginal consideration.4

The dominant view among the Palestinian leadership in subsequent decades reflected Sayegh’s argument. Later, in the 1990s, when Fateh accepted a Quisling role as administrator of the Occupied Territories on behalf of Israel, Hamas picked up the strategy of armed struggle abandoned by the PLO. The Palestinian resistance movement also increasingly deployed the tools that Ahmad had long recommended. In 2005, the boycott, divestment and sanctions (BDS) campaign was launched, aiming to impose a moral isolation on Israel, and a more advanced infrastructure of ideological campaigning took shape, powerfully engaging international public opinion. More recently, there has been the popular resistance of the March of Return. None of it has been sufficient to prevent Israel’s relentless colonial violence. Today, Israel is carrying out the high-tech mass murder of a besieged people, deliberately destroying every part of their civilian infrastructure and violently herding them into concentrated areas where they are deliberately bombed while cut off from food, water, electricity and medical assistance. The US provides unabashed military, financial and diplomatic support, with a veneer of insipid expressions of concern. Yet, it has also become clear that Israel is losing the ideological battle in the west as a result of the Palestinians’ broader political mobilisations. If this portends new possibilities for Palestinian liberation, Ahmad’s argument may yet prove correct.

A refugee of partition

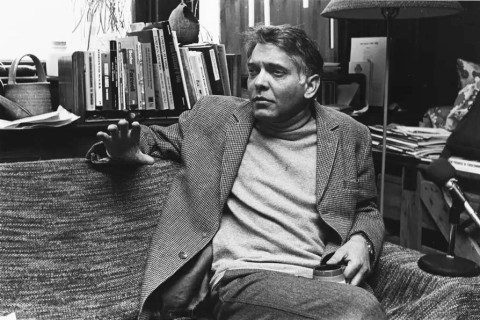

Born to a family of Muslim landowners in Bihar in British colonial India, in 1933 or 1934, Eqbal Ahmad was a three- or four-year-old child when he awoke one night to the sight of machete-wielding attackers murdering his father. It was a traumatic early lesson in the causes of political violence: other landowners had ordered his father’s murder as punishment for betraying his class by taking up peasant causes. A decade later, Ahmad was forced to leave his ancestral home, due to the British partition of India and Pakistan along broadly religious lines. Making the long trek to Pakistan on foot along India’s Grand Trunk Road, he witnessed the horrors of communal violence between Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims, and had to use a gun to ward off attackers. Eventually settling in Lahore, he dropped out of college to spend four months as a volunteer fighter with a Communist Party unit in Kashmir, leaving after being shot. He completed his studies of economics and history at Foreman Christian College in Lahore.5

In 1957, having already by his mid-20s experienced three different forms of political violence, Ahmad left for the US on a scholarship and arrived in Princeton the following year for graduate studies in politics. After moving to Tunisia five years later to study the country’s trade union movement, he befriended leaders of the national liberation movement in neighbouring Algeria. Among them was Frantz Fanon, the Martinican revolutionary then heading the Tunis information office of the Algerian FLN and editing its underground newspaper, El Moudjahid. In the last six months of Fanon’s short life, he worked closely with Ahmad.6

Beginning an academic career in the US during the 1960s, Ahmad was one of the few professors who publicly objected to the US war in Vietnam. It was even less common to criticise Israel’s occupation of Palestine, and he joined the handful, including Fayez Sayegh and Ibrahim Abu-Lughod, willing to do so publicly. His job prospects suffered as a result. As the movement against the Vietnam war stepped up, Ahmad was part of a group helping to hide the anti-war Jesuit priest Daniel Berrigan, who was on the FBI’s most-wanted list after being accused of destroying military draft records. In 1971, the FBI concocted an indictment of Ahmad and six other peace activists, all priests or nuns, charging them with plotting to kidnap national security advisor Henry Kissinger and blow up government buildings. The jury was not persuaded and the so-called Harrisburg Seven were acquitted of the major charges.7

The trial propelled Ahmad to national renown in the US and, until his retirement from Hampshire College in 1997, he was one of the pre-eminent commentators on imperialism, nationalism, authoritarianism and insurgencies in the Middle East and South Asia. From 1973 to 1975, he served as the first director of the Transnational Institute in Amsterdam. Ahmad died in Pakistan in 1999. His influence lives on, imparted as much through storytelling at his famous late-night salons as through his published writing and interviews.

AP Wirephoto, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

A twentieth-century settler colonialism

While Eqbal Ahmad and Fayez Sayegh disagreed about resistance strategies, they both analysed Zionism as a form of settler colonialism. In his landmark Zionist Colonialism in Palestine, published in 1965, Sayegh argued that Zionism aimed at establishing first a ‘settler-community’ and then ‘a settler-state in Palestine’, in imitation of the colonial ventures of European nations in earlier centuries. ‘If other European nations had successfully extended themselves into Asia and Africa, and had annexed to their imperial domains vast portions of those two continents’, he wrote, ‘the “Jewish nation” – it was argued – was entitled and able to do the same thing for itself’. There is no shortage of statements from Zionist leaders that support this interpretation. The architect of modern Zionism Theodor Herzl wrote in 1896 that a Jewish state in Palestine would be ‘a portion of the rampart of Europe against Asia, an outpost of civilization as opposed to barbarism’. The same colonial stance recurred in 1947, when Chaim Weizmann, later to be Israel’s first president, stated before the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine:

Other peoples have colonized great countries, rich countries. They found when they entered there backward populations. And they did for the backward populations what they did. I am not a historian, and I am not sitting in judgment on the colonizing activity of the various great nations which have colonized backward regions. But I would like to say that, as compared with the result of the colonizing activities of other peoples, our impact on the Arabs has not produced very much worse results than what has been produced by others in other countries.

Today, the theme of Israel as an outpost of western civilisation continues, with, for example, Israeli President Isaac Herzog declaring in December 2023 that the war on Gaza is ‘really, truly, to save Western civilization, to save the values of Western civilization’ and that, if it weren’t for Israel, ‘Europe would be next’.8

While Sayegh saw an analogy between Zionism and nineteenth-century European colonialism in Asia and Africa, he also pointed to important differences. Crucially, for Zionism ‘colonization would be the instrument of nation-building, not the byproduct of an already-fulfilled nationalism’. Moreover, because Zionism was an ‘anomaly’ – a colonialism launched in an era of decolonisation – it had to confront the problem that Palestinians themselves had developed national aspirations. This is why it has ‘so passionate a zeal’ for the ‘physical expulsion of “native” populations’. Zionist colonists aim, ultimately, not at establishing a South Africa in the Middle East where Palestinians are subordinated into a racially separated, super-exploited workforce, but at the complete elimination of the Palestinians. When it is unable to achieve this goal, says Sayegh, it settles for an ‘apartheid’ state of racial segregation. Either way, racism is ‘the quintessence of Zionism’. More than 50 years after Sayegh wrote Zionist Colonialism in Palestine, Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International acknowledged that Israel operated an apartheid system. Missing from their accounts, though, was an explanation of why Zionism contains an impulse towards racist exclusion. Without discussing the dynamics of settler colonialism which Sayegh had outlined, Israel’s segregationist policies appeared as the result of individual decisions by racist politicians rather than expressions of a deeper structural process.9

Eqbal Ahmad’s most detailed analysis of Zionism – ‘“Pioneering” in the nuclear age: an essay on Israel and the Palestinians’ – was published in 1984 in the journal Race & Class. Reading the essay today, it sizzles with insights that feel contemporary. Because the underlying logic of Zionist colonialism has not changed over the last half century, Ahmad’s analysis of it remains applicable. Echoing Sayegh, Ahmad thought that, while there were similarities to South African apartheid, Zionism was ‘structurally and substantively’ different. The more precise comparison, he argued, was to European settler colonialism in the Americas. With both, there were ‘the myths of the empty land, of swamps reclaimed and deserts blooming … messianic complexes of manifest destinies and promised lands … a paranoid strain in the colonising culture, an instrumental attitude towards violence and a tendency to expand.’ He noted that settler colonies of this kind tend to pursue three goals: some level of independence from their western state sponsors; a normalisation of their relations with neighbouring countries; and a solution to what they consider the ‘native problem’, through the elimination, expulsion or containment of the Indigenous populations.10

The US could claim it had achieved these goals in the nineteenth century, though Indigenous resistance has never ceased. Israel was still pursuing them in the 1980s and continues to do so today. Its pursuit of autonomy from its sponsor, the US, has been complex. On the one hand, it has sought to integrate its agenda closely into US ruling elites, to lesson the likelihood that they might place restrictions on Israeli colonialism. On the other hand, Israel has steadily reduced its financial and military dependence on the US. US financial assistance is now a much smaller fraction of Israel’s gross domestic product (GDP) than it was 40 years ago. In 1981, US aid was equivalent to almost 10% of Israel’s economy; in 2020, though higher in absolute terms, the $4 billion the US provided was closer to 1%. Israel’s arms industry means it is not entirely dependent on importing US-made weapons, but the country still needs US military and diplomatic protection: it relies on the US to block attempts by other forces in the region to militarily assist the Palestinians – as shown by the US-led bombing this year of the Ansar Allah (Houthi) group in Yemen – and to use its seat at the UN Security Council, where it routinely vetoes resolutions aimed at restraining Israeli violence. If Israel’s normalisation has been within reach, it is because the US put its weight behind the Abraham Accords that formalised Arab states’ recognition of Israeli sovereignty.11

It is the third goal of settler colonialism – resolving the ‘native problem’ – where Israel has its greatest difficulty. Throughout its history, it has deployed various methods to expel Palestinians: ongoing removal from their homes under discriminatory laws and regulations, intimidation and violence to pressure them to leave, and ethnic cleansing under the cover of war, as happened in 1948, 1956 and 1967, and is now occurring again in the West Bank and Gaza. The inhuman geography of the Gaza strip – where 2.3 million Palestinians, mainly refugees, are penned in, besieged, deliberately starved and deprived of clean water, and subjected to regular bombardment – is itself a product of this process of enforced displacement from other parts of Palestine. Israeli leaders apparently now believe that even in this narrow slice of land, one of the world’s most densely populated locations, there are opportunities for settler expansion, if those Gazans who survive the genocidal war can be squeezed into the southern half, or even expelled into Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula. The current policy on Gaza is being carried out by the most extremist leadership in Israel’s history but its violence flows not from a particular party but from the basic premises of the Zionist project. The aim has always been to smash the Palestinian nation into a thousand shards, so that its people are concentrated and contained in ever narrower patches of their land, while heavily armed and well-resourced Jewish settlements expand relentlessly. Yet, despite the persistent application of Israeli terror, there remain more than 7 million Palestinians living between the Jordan river and the Mediterranean, with another 6 million living in neighbouring countries, many in refugee camps and most set on returning to their homeland. Israel will probably not succeed in its current objective of dismantling Hamas but, even if it did, the Palestinian struggle for national liberation will continue.12

Israel was, of course, itself established by refugees. But rather than seeing this as a factor that made Israel exceptional as a colony, Ahmad pointed out that it was not unusual in the history of settler colonialism. Zionism was similar to the European colonies of North America, he noted, in the way it offered refuge to persecuted religious minorities in Europe, inclining its advocates to a rhetoric of liberal rights even as it sought ‘to exclude and eliminate the native inhabitants’. Later, Israel’s European leaders brought in Jews from Middle Eastern countries, as part of their effort to demographically supplant the Palestinians – garnishing Israel’s reputation as a refuge, even though these new citizens were in a subordinate social position. Where Zionism is exceptional is that, in forming a settler colonial state in 1948, at a later stage of history, it has been forced to develop a more advanced repertoire of colonial methods. The ‘unique fate’ of the Palestinians, Ahmad wrote, was their encountering ‘a remarkable phenomenon – a settler colonial movement in the twentieth century, an infinitely better organised, more desperate, more disciplined, more complex, if inherently weaker, movement than its predecessors’. That capacity to be ruthlessly well-organised could be seen, for example, in the way that Israel developed itself into one of the world’s largest arms exporters. By supplying weapons or counterinsurgency training to US-allied right-wing authoritarian regimes in South Africa, Argentina, Chile, Guatemala and Honduras, when the US was unable to act itself because of domestic or diplomatic concerns, Israel created ‘new and organic linkages’ with the US ruling class. ‘The significance of this development’, wrote Ahmad, ‘cannot be overstated’.13

Equally important were the sophisticated ways that Israel managed the demographic challenges inherent to any settler state. As its developing capitalist economy increasingly relied on Palestinian labour, Israeli leaders anticipated the longer-term danger this presented to their project. They observed how in South Africa, by the 1980s, the structural dependence on a large Black workforce was a dangerous vulnerability, because labour strikes could be used by the anti-apartheid movement to weaken the system. Israel avoided a similar fate by continuously seeking new pools of Jewish labour (such as from the former Soviet Union), concentrating on capital-intensive industries (such as the manufacturing of high-tech surveillance and military products) and bringing in temporary migrant workers from Asia.14

Vince Musi / The White House, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The road to Oslo

When Eqbal Ahmad was laying out his analysis of Zionism as settler colonialism in the 1980s, the dominant viewpoint was organised instead around a partition framework. This interpretation of the issue narrows the canvas of Zionist crimes to the military occupations of 1967, and the question is whether a viable Palestinian state can exist in the West Bank and Gaza, partitioned from an Israel defined by at least the ‘Green Line’ of the 1949 armistice, constituting approximately 78% of historical Palestine. Accepted in this approach is Zionism’s fragmentation of the Palestinians into three categories – second-class citizens of Israel living within the Green Line, subjects of the military occupations in the West Bank and Gaza, and the refugees living in neighbouring countries and further afield – and the remedy proposed for each category is separate and distinct. The settler colonial perspective, on the other hand, treats the Palestinians as a single people and 1948, not 1967, is the decisive moment; indeed, Sayegh’s classic statement of the settler colonial argument was written before 1967. By the mid-1970s, though, the PLO was moving away from the settler colonial analysis that Fayez Sayegh, and other affiliated intellectuals like George Jabbour, had developed. Instead, it adopted the partition paradigm, centring the conflict upon the line to be drawn between Israel and a future Palestinian state. With his teenage experience of internecine violence in the division of India and Pakistan, Ahmad had a natural antipathy to partitions as outcomes of anticolonial struggles. But with the 1993 Oslo Agreement, partition was formalised and the question of Palestine was reduced in most people’s perception to a land dispute between two national identities that would have to make peace with a two-state solution.15

For a while, this meant the framework of settler colonialism received little attention. But as it became clear since the turn of the century that Oslo would not be the basis for a Palestinian state but rather a way to preserve the military occupation while Zionists expanded their settlements, there was renewed interest in the framework. The recent popularity of the slogan ‘From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free’ – with its demand for freedom across the whole of historical Palestine – is one expression of this revival. So much so that a string of articles has recently appeared in US media outlets criticising the use of the term ‘settler colonialism’ in relation to Israel as, at best, trendy academic jargon and, at worst, implicitly antisemitic. In the New York Times, for example, Bret Stephens wrote that to describe Israel as settler colonialism is ‘invidious, hypocritical and historically illiterate’, an ‘interesting, but fatally flawed, academic’ theory. To talk of settler colonialism, these articles argue, implies wanting to turn back the clock to before Israel’s creation in 1948, which they equate with desiring the expulsion of Jews. But ending settler colonialism in historical Palestine requires not the absence of Jews but the absence of Jewish supremacy. A settler colonialism analysis does not itself determine what state or states should be created between the Mediterranean and the River Jordan; all it requires is that Jews and Palestinians have equal rights in that territory. Moreover, there is no validity to the claim made in these articles that the settler colonialism framework was recently invented by US professors who wished to sound radical while remaining aloof from the dangerous practical consequences of their position; the framework was not in fact created in US academia but is the product of many decades of strategic thinking within the Palestinian resistance movement.16

Moral isolation of the adversary

‘After seeing what I saw in Algeria’, Eqbal Ahmad told an interviewer, ‘I couldn’t romanticize armed struggle’. Not only was the civilian toll among Algerians very high, he noted, but also, in fact, ‘the Algerians lost the war militarily’. Freedom from French colonialism came not from the armed campaign itself but from the political mobilisations that generated a growing recognition around the world that France was in the wrong in trying to hold onto the territory. ‘They were successful in isolating France morally. So, the primary task of revolutionary struggle is to achieve the moral isolation of the adversary in its own eyes and in the eyes of the world’. Campaigns of violence could be devastating, he argued, not just for colonial oppressors but also for the oppressed, not just because of the retaliation that colonialists were capable of, but also because of the possibility that the violence first mobilised against colonialism could later be directed against sections of the colonised population, especially when the violence of political struggle fused with a narrow conception of identity.17

At the same time, Ahmad thought there are circumstances in which armed struggle is necessary. What matters is that it is carried out within a broader framework of revolutionary politics, so that it is not indiscriminate in choosing its victims and aims at broadening political support rather than alienating potential allies. Movements that ground their struggles in a particular territory and seek the revolutionary mobilisation of the peoples who live there tend to be ‘sociologically and psychologically selective’ in their use of violence, he pointed out. They strike ‘at widely perceived symbols of oppression – landlords, rapacious officials, repressive armies’ and aim at ‘widening the revolutionaries’ popular support by freeing their potential constituencies from the constraints of oppressive power’. Effective resistance, he believed, requires a flexible approach in which multiple military and political tactics are combined, depending on the adversary’s position and the broader political context, rather than seeing violence and non-violence as absolute and mutually exclusive strategies in themselves. In this sense, Ahmad’s analysis of political violence had a different basis from recent left-wing condemnations of Hamas’ violence on straightforward moral grounds.18

Among the examples Ahmad cited of the effective use of revolutionary violence were the Chinese and Cuban revolutions, the African National Congress’ armed struggle against apartheid in South Africa, and the Partido Africano da Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde (PAIGC), which freed Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde from Portuguese colonialism. In these cases, Ahmad argued, a grounding in revolutionary ideology encouraged a strategic depth and a recognition that liberation struggles are not simple clashes between opposed identities – oppressed and oppressor – but ultimately reach beyond the identities that systems of oppression produce; on this point, he often quoted Aimé Césaire’s line: ‘There is a place for all at the rendezvous of victory’.19

This approach also precluded the temptation of claiming ‘easy victories’ in armed struggle, as the PAIGC’s leader Amilcar Cabral put it. Ahmad’s worry was that ‘weak people, where they do not know how to fight, create myths about their strength’. The danger is that a movement will derive its ‘morale and sense of momentum from constant triumphalism, from claiming progress where there has been only a certain amount of motion, confusing small gains with major victories’. This exaggerated sense of strength is often further encouraged by oppressors declaring how terrified they are of resistance. But ‘the strong will always call the weak “very dangerous” before they destroy the weak’.20

Nubar Hovsepian, an Armenian from Egypt who is now an Associate Professor of Political Science and International Studies at Chapman University, California, worked closely with Eqbal Ahmad on the Palestinian cause, sometimes acting as a courier carrying letters between Palestinian leaders in Beirut and Ahmad in New York. ‘Eqbal believed that it’s the discipline of detail, the out-organizing of the adversary’, he recalls. To out-organise meant, as Ahmad put it in 1983, ‘mobilization of international support and moral isolation of the enemy … addressing not so much the governments but the civil societies in the adversary’s strongholds, in this case the Israeli and American publics’. The point of engaging those civil societies was not to find points of compromise but ‘to expose the basic contradictions of the adversarial society. Israel seeks legitimacy as the haven of a long-persecuted people, but it is founded on and still expands at another people’s cost. There is a schizophrenic character to Israel’s political and cultural life which every Israeli knows at some level. This tension must be forced into the open [by] … systematic and persistent political agitation.’21

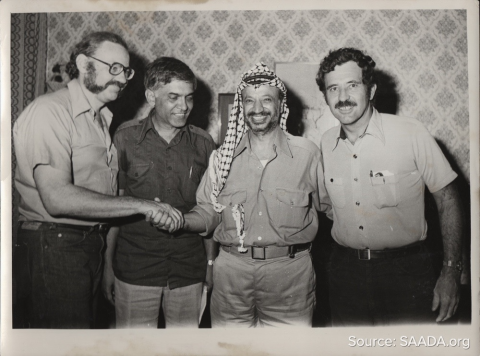

Courtesy of Julie Diamond and SAADA / https://www.saada.org/item/20170128-4933

Ahmad and the PLO

In the 1970s and 1980s, Ahmad hoped the PLO could develop into ‘an organization complex and disciplined enough’ to carry out the kind of resistance he envisaged. To this end, Ahmad travelled regularly to the Middle East to meet with the PLO leadership, including Arafat, and make the case for widening its strategy beyond military and diplomatic methods. Ahmad was often accompanied by his friend Edward Said, the famous Columbia University scholar and, from 1977, an independent member of the Palestine National Council, the Palestinian parliament in exile. In one meeting, Ahmad advocated a massive march on Israel by unarmed Palestinians, carrying banners that said ‘we want to go home’. The idea was met with ‘disbelief and mild panic’, recalled Said. At another meeting in Beirut, Ahmad recommended the PLO create an organisation in the US to lobby for the Palestinian cause, on the model of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC). When PLO delegates attended the United Nations in New York in 1975, Ahmad met them and argued they should start a campaign to win support from US civil society, including Jewish elements who were beginning to question Israel. Through the 1980s, Ahmad continued to argue that the PLO ought to build a stronger political operation within the US to weaken support for Israel. ‘I have spoken to Arafat about this line in great detail probably five or six times’, Ahmad later recalled. ‘He always took notes, always promised to do things, always did nothing.’22

Arafat, it turned out, was ready to accept a role as an administrator of Palestinian enclaves without any plausible prospect of a sovereign state, a fatal mistake that only prolonged the occupation. Said privately concluded in 1989 that the Palestinian leadership was ‘not up to the caliber of the people’s stubborn and resourceful will to resist’. For Ahmad, the PLO ‘built an apparently opulent quasi-state before it had matured as a liberation movement’. The combination of lavish funding by Arab states, a distance from everyday life in the Occupied Territories and the absence of a broader political strategy made the PLO leadership vulnerable to being co-opted. The Oslo process of the 1990s was the means by which that happened. When Ahmad and Said publicly criticised the Oslo Accords as a capitulation, they were frozen out by Arafat.23

Hamas first emerged in the 1980s with financing from Israel, which hoped it would be a counterweight to Fateh.24 But a decade later Hamas filled the vacuum left by Arafat’s entry into the Oslo process. The more that Fateh’s leaders appeared to be complicit with the occupation and corrupt in their administration of the external funding that propped up the Oslo-created Palestinian Authority, the greater Hamas’ popularity among Palestinians. With its campaign of suicide bombing during the second intifada from 2000, western policymakers and self-styled terrorism experts described Hamas as an expression of ‘radical Islam’ and associated with al-Qaeda. The argument was that, unlike earlier national liberation formations, such as Fateh, the FLN in Algeria, or the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) in Northern Ireland, retrospectively labelled as secular, Hamas was fanatical and unsparing in its violence because its motivation was a millenarian, antisemitic hatred, seeded by religious extremism. That view was certainly encouraged by the group’s antisemitic founding charter of 1988, which called for the creation of an Islamic state over the entirety of the land of historic Palestine. But the most plausible interpretation of Hamas since then is that it has adopted the PLO’s former strategy of attempting to weaken Israel’s occupation through a sustained war of attrition. At the same time, its participation in the Palestinian Authority’s municipal and legislative elections in 2006, in which it emerged the largest party, demonstrated a willingness to play a governing role within the Oslo structures. The US and Israel subsequently organised a coup to prevent this, leading to Fateh retaining control of the Palestinian Authority in the West Bank enclaves and a Hamas administration circumscribed to Gaza and subject to an Israeli blockade. Thereafter was what Tareq Baconi calls a ‘violent equilibrium’, with Hamas using missile attacks to pressure Israel to ease its blockade and Israel deploying overwhelming force to collectively punish the people of Gaza.25

Popular resistance

The political separation of Gaza from the West Bank added to the divisions of the Palestinian movement. Palestinians were ‘closed off in separate geographic enclaves’, wrote Walid Daqqah from an Israeli prison in 2011, in order to shatter ‘the system of collective values that embodies the concept of one unified people’ and thereby ‘to mold Palestinian consciousness’ into passivity and individualism. But in the 2000s, new hopes for overcoming that fragmentation arose from a flourishing of Palestinian popular mobilisation outside the armed struggle paradigm. Eqbal Ahmad was no longer alive to see it but something closer to his vision of resistance was taking shape. One example was a broad range of Palestinian political parties, unions and other organisations calling for BDS initiatives against Israel, similar to the trade and sports embargoes applied to South Africa in the apartheid era. The three BDS demands were designed to cover all segments of the Palestinian people – refugees, those under occupation, and citizens of Israel. In viewing these as ‘the three integral parts of the people of Palestine’, the call moved beyond the partitionist framework and the Oslo focus on a state in the Occupied Territories. Another example was the March of Return in 2018. Weekly demonstrations began along the fence between the Gaza Strip and Israel that were both against the siege and for the right of Palestinians to return to homes in historical Palestine from which they had been forced out, an idea echoing Ahmad’s earlier proposal for unarmed Palestinians to march on Israel with banners proclaiming ‘we want to go home’. On Nakba Day that year, Israeli forces killed over 59 unarmed participants in the marches, prompting more protests across Palestine.26

Three years later, popular resistance continued when Palestinian residents of the Sheikh Jarrah neighbourhood in East Jerusalem, many of them refugees from the displacements of 1948, were ordered to be evicted and their homes handed over to Israeli settlers. Palestinians mobilised in the West Bank, within the Green Line, and at the Lebanese and Jordanian borders, uniting the different segments of the Palestinian nation in a shared protest that implicated all the violently enforced expulsions of Zionist settler colonialism. This was followed by a general strike of Palestinian workers on both sides of the Green Line. Its leaders issued a manifesto that referred to a new chapter of united struggle against settler colonialism:

We are one people and one society throughout Palestine. Zionist mobs forcefully displaced most of our people, stole our homes and demolished our villages. Zionism was determined to tear apart those who remained in Palestine, isolate us in sectional geographical areas, and transform us into different and dispersed societies, so that each group lives in a separate large prison. This is how Zionism controls us, disperses our political will and prevents us from a united struggle against the racist settler colonial system throughout Palestine.

Encompassing all Palestinians irrespective of their location within the structures of Zionist colonialism, these grassroots initiatives reached beyond Oslo’s partitionist framework. Their emergence was a pivotal moment in the Palestinian national struggle, wrote Mouin Rabbani, co-editor of Jadaliyya, because it meant ‘the municipal model of Palestinian politics has been shattered’. Though they were not sustained long enough to fully set in motion a new politics, they did generate a vision of future possibilities.27

The popular mobilisations of 2018 and 2021 were also supported by Hamas. Fearing it would end up no more than a service provider in a blockaded Gaza, upholding a colonial status quo, Hamas decided the popular protests offered ways to alter the ‘violent equilibrium’ in which it found itself. In 2021, it issued an ultimatum stating it would fire rockets if Israeli forces did not leave Sheikh Jarrah. Israel did not withdraw and responded by bombing Gaza, killing 256 Palestinians and injuring nearly 2,000.28

Moving beyond a suffocating status quo was perhaps also the motivation for Hamas and other armed groups to launch Operation Al-Aqsa Flood on 7 October 2023. During the surprise attack that breached the siege of Gaza, around 1,200 people were killed in Israeli communities and military bases, and 250 hostages taken. ‘The choice, as Hamas saw it’, writes Baconi, ‘was between dying a slow death – as many in Gaza say – and fundamentally disrupting the entire equation’. Today, much of progressive western opinion hopes for a Palestinian resistance without Hamas. While Palestinians vary in their opinion of Hamas’ policies, there is broad acceptance that the faction is an integral part of their liberation struggle – for good reason: a people suffering genocide can hardly be expected to abandon the most significant armed group operating in their defence.29

Paradoxes of the present

Since the Hamas offensive, there has so far been no ideological fragmentation in the Zionist camp or substantial isolation of Israel from supporting governments elsewhere. Israeli society has for the time being united around Netanyahu’s government. Support from the Biden administration is solid, despite extensive demonstrations within the US and large numbers of Democrat supporters threatening to withdraw their vote for Biden in this year’s presidential election. In France and Germany, solidarity with the Palestinian cause is vehemently suppressed. In the UK, new legislation is being introduced to bar local authorities and universities from introducing BDS policies, and ministers are discussing whether to include support for Palestine in the official definition of extremism. The prevailing view among both the liberal and conservative wings of western leaders and governments is that support for Israel is an absolute commitment.30

At the same time, outside the ruling elites, solidarity with Palestine has surged to the forefront of global consciousness. This is not only a spontaneous reaction to the horrifying images of suffering in Gaza but also the result of over two decades of strong, grassroots organising, especially in the US, some countries in Europe, and South Africa. In recent months, millions of people spanning every continent have participated in demonstrations to call for Israel to end its military assault on Gaza and vacate its military occupation of the West Bank. The groundwork for this flowering of worldwide opposition to Zionism was laid in large part with the BDS campaign.

Israel is now losing the propaganda war. Attempts to present Palestinian resistance as ‘just like ISIS and Al Qaeda’, as Israeli president Isaac Herzog put it in the New York Times, have not been persuasive. Increasingly, victories are being won in the US and Europe at the level of public opinion, trade unions, professional organisations, and other elements of civil society. While support for Palestine can still get you fired from a US academic job, the extent of that support is far wider than it has ever been before. Despite the universally pro-Israeli appearance cultivated by the major Jewish organisations in the US, American Jews are now sharply divided in their views. The ‘shift to a small number of ultra-wealthy donors’, writes journalist Peter Beinart, ‘has insulated American Jewish organizations from political trends among American Jews as a whole’. Unlike two decades ago, today it is Israeli leaders rather than Palestinians who are described in the US media as rejecting the Oslo peace plan.31

Above all, the partitionist framework that for decades dominated understanding of the Palestine question has crumbled. While it is still proclaimed by government officials in the US and most European countries, over 20 years of organising has made mainstream an understanding of Israel as a settler colonial apartheid state. Eqbal Ahmad would have despaired at the current Israeli mass slaughter taking place in Gaza and lamented the absence of a Palestinian governing body able to effectively organise a multi-faceted resistance; despite its limitations, the PLO of the 1970s and 1980s was still a vehicle for national representation and mobilisation. But he would have drawn some optimism from the unprecedented recent surge in global solidarity and its embrace of a settler colonial analysis of Zionism. And today, just as before, suggests Nubar Hovsepian, ‘Eqbal would probably still be saying we need to be more creative in outmaneuvering the enemy’.32