Green hydrogen in Tunisia A new mechanism of plunder and exploitation

Tunisia's Green Hydrogen Strategy, developed with Germany's GIZ, plans to export over 6 million tonnes to Europe by 2050. While praised, it overlooks the significant costs to Tunisia's vital sectors, prioritizing EU needs over local interests.

Illustration by Othman Selmi | www.behance.net/othmanselmi

In September 2023, the Tunisian Ministry of Industry, Energy and Mines issued the National Strategy for the Development of Green Hydrogen and its Derivatives in Tunisia, which it had developed in partnership with the German Agency for International Cooperation (GIZ).1 The National Strategy includes an action plan for exporting more than 6 million tonnes of green hydrogen to Europe by 2050. This plan, along with a number of statements by Tunisian officials in charge of the country’s energy transition, has been met with a number of positive articles, which hail it as a potential boost for the country’s development. However, the Strategy’s aim of meeting the European Union’s (EU’s) needs and complying with its dictates will undoubtedly come at a great cost to a number of important sectors in Tunisia – a fact that seems to have been ignored in the general applause the Strategy has received. Against this background, the present article, developed by the Working Group for Energy Democracy in Tunisia, seeks to unveil elements of this major project that have previously remained undiscussed.

Green Hydrogen: why and who truly benefits?

The EU is striving to make major investments in renewable energy, and green hydrogen in particular, in order to alleviate its dependence on Russian gas and to profit from a new market for which it aims to be a pioneering force. In addition, the EU aims to decrease its carbon emissions by 55% by 2030, and to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. These ambitions are set out in the EU’s Hydrogen Strategy,2 adopted in June 2020, and are also mirrored in Germany’s National Hydrogen Strategy3, as well as the REPowerEU Plan4, which sets the target of 10 million tonnes of hydrogen produced within the EU by 2030, alongside the importation of an additional 10 million tonnes.

Figure 1: The colors of Hydrogen - source: Corporate Europe Observatory and Transnational Institute (2022) Assessing EU plans to import hydrogen from North Africa

Illustration by Othman Selmi | www.behance.net/othmanselmi

The True Cost – and the Illusion – of Development

The Tunisian Government is selling the idea that producing green hydrogen in Tunisia will yield substantial financial revenues for the country and allow it to gain a foothold in the European market. However, it is ignoring the fact that these projects will further enhance the already unbalanced scale of power between Tunisia and the EU. This imbalance is due to the fact that, like most countries in the South, Tunisia suffers from some major structural deficiencies, the most important of which are the following12:

- Tunisia is highly energy dependent, due to its inability to process raw materials owing to its lack of the necessary technology. The country has only one refinery for processing raw petroleum, which is located in the north (Zarzouna, Bizerte). This has a refinery capacity of 34,000 barrels per day: as against Tunisia’s production of 50,000 barrels per day. Refinery capacity thus does not even meet the volume of raw petroleum produced in Tunisia, let alone meeting the overall national demand. Tunisia is thus obligated to export its raw materials (unrefined petroleum in this case) and to pay the difference in the cost between raw petroleum and its derivatives, which exacerbates the deficiency in its trade balance. In regard to electricity, due to Tunisia’s total reliance on natural gas for electricity production, more than half of its internal demand is met by importation from Algeria13.

- Tunisia also faces a high level of food dependency. The importation rate of soft wheat (which is an essential component of Tunisians’ diet) stood at 94% in 202014. At the same time, the country exports water-intensive produce such as strawberries, tomatoes, dates and olive oil, in addition to a number of other agricultural products sought by European and Western consumers. The production of all of these products has serious environmental costs for Tunisia. To these costs are added the fact that agricultural lands can now be used for renewable energy projects, without changing their land tenure status and without needing to obtain a permission from the Ministry of Agriculture (as required by Decree No. 2022-68). This will further aggravate the agricultural crisis in the country15.

- Tunisia specialises in low added-value industries, such as assembly and textiles, which work as subcontractors for multinational conglomerates that are drawn by the country’s cheap labour, raw materials, and low costs of water and electricity, in comparison with their countries of origin. Here, it is important to note the pattern of relocating polluting industries that have a heavy ecological toll from Global North countries to those of the Global South. It is in this context that green hydrogen export projects should be seen, especially in relation to the issue of water.

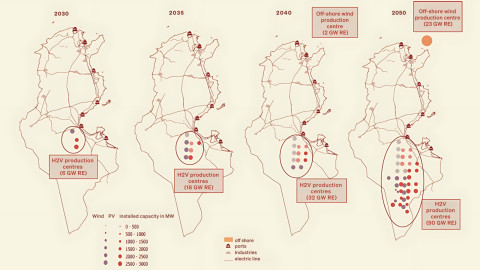

In order to achieve the goal set by the National Strategy for the Development of Green Hydrogen and its Derivatives in Tunisia of exporting 6 million tonnes of green hydrogen by 2050, more than 90 Gigawatts of renewable energies must be mobilised16(both aeolian and photovoltaic) in order to power the process of extracting hydrogen gas (H2) from desalinated sea water (H2O). This is 15 times the current power capacities – of all types (renewable and non-renewables) – in the country. To achieve this level of renewable energy production, more than 500,000 hectares of land (approximately 3% of Tunisia’s total surface)17 will be allocated for renewable energy projects. These lands will include seized community lands (as in the case of Segdoud in Gafsa)18 and state-owned lands, which will be offered on a silver plate to investors.

In addition to the energy requirement, to provide the desalinated water needed for the production process, it will be necessary to establish water desalination stations with a capacity of 160 million cubic metres per year. This is equivalent to the annual consumption of 400,000 Tunisians (based on an average of 400 cubic metres per capita) in a country that faces recurrent droughts and that experiences increasing difficulties in providing drinking water for its own citizens. Indeed, civil society bodies working in the water sector have recently sounded the alarm about the water situation in the country and the measures that need to be taken to resolve it, the most important of which is to immediately put an end to the depletion of water resources in the service of lucrative business at the expense of the people and the environment19.

Figure 2: The distribution of lands producing renewable energies allocated to the green hydrogen production process | source: Ministry of Industry, Energy and Mines and GIZ (2023). op.cit.

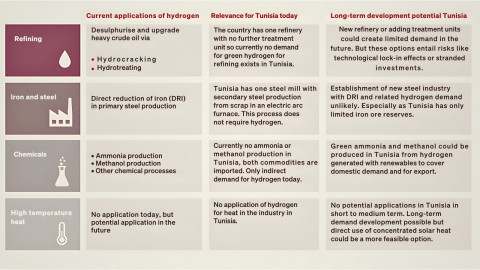

In addition to the risks to the environment set out above, it is worth underlining how Europe, rather than Tunisia, will be the big winner from the unequal and asymmetrical relationship set out in the National Strategy for the Development of Green Hydrogen and its Derivatives in Tunisia. A study published by GIZ in 202120 evaluating the economic opportunities of, and various challenges facing, investments in green hydrogen in Tunisia points out that the Tunisian industrial landscape is not currently adapted to benefit from green hydrogen in sectors such as transportation and steel. The only benefit the study identifies is the use of green hydrogen to produce certain derivatives that Tunisia currently imports (see Figure 2). Thus, the approach set out by the National Strategy exclusively revolves around exporting raw materials to the EU (both in the medium term and long term) so that European countries can meet their targets for reducing their industrial carbon emissions.

Figure 3: The potential uses of green hydrogen derivatives in Tunisia | source: The figure is taken from GIZ (2021) ‘Study on the Opportunities of “Power- to – X” in Tunisia’.

‘A homeland… is when none of that happens’*: Our alternatives

* Kanafani, Ghassan. (1969) Returning to Haifa. Lynne Rienner Publishers

Before the war in Ukraine broke out in February 2022, the Tunisian Electricity and Gas Company (STEG) issued the document ‘Managing the Volatility of Renewable Energies using Hydrogen’21. This document argues that green hydrogen can enhance the resilience of, and ensure the optimal management of, Tunisia’s renewable energy sector, which is currently plagued by recurrent cuts due to the inability to control production rates throughout the year. As shown in a graph in the document, in those seasons in which the local consumption of electricity drops, it is currently unfeasible to exploit all of the electricity produced by renewable energy sources. The document argues therefore that adopting green hydrogen can provide an energy reserve to overcome this problem and it sets out necessary measures (albeit without detail) to be taken in order to reach the set goals, such as preparing a national strategic programme for green hydrogen and an action plan to identify how produced green hydrogen can best serve the national interest.

Thus, as also indicated in the STEG document, the main aim of producing green hydrogen, as initially stated, was to overcome the problems of intermittence and fluctuations created by the Tunisian Solar Plan22. However, due to the energy crisis in Europe (Germany in particular) over the last two years, as a result of the war in Ukraine, the aforementioned aim was abandoned as GIZ lobbied to steer the hydrogen plans towards exporting the majority of Tunisia’s green hydrogen production. GIZ achieved this through overseeing development of the National Strategy for the Development of Green Hydrogen and its Derivatives in Tunisia.

What alternative approaches could be applied to overcome the challenges set out in the National Strategy in a manner that benefits Tunisia, rather than fulfilling the EU’s neocolonial ambitions?

Before answering this question in regard to green hydrogen, it is necessary to first address the issues that have led Tunisia to adopt the approach set out in the GIZ-shaped National Strategy, and to allow foreign agencies to interfere in its energy policies. Perhaps the starkest example of this dynamic is the current Tunisian Solar Plan. The plan, which the government considers the optimal solution to the country’s energy crisis, has itself become a problem. It does not meet Tunisia’s actual requirements, but rather merely echoes the recommendations and dictates of the West (especially the EU). It is thus necessary to amend the plan by, first, reviewing the distribution of renewable energy projects to be implemented. The over-estimated amounts of wind power in the plan do not align with the specificities of Tunisia’s electricity consumption, notably, peak consumption during summer (when wind availability is limited) remains unaddressed. This means the country remains dependent on imported natural gas, especially in the summer (a peak period for demand), which poses problems with regard to access to electricity. As an alternative to wind and gas it is essential to rely on solar power, either thermal or photovoltaic, which allows for a relatively stable amount of electrical power throughout the year despite fluctuations in the summer, considering the country’s high levels of solar radiation. This will help reduce the consumption of natural gas and will ensure greater reliability of electricity supply when compared to wind power.

Moreover, it is also necessary to establish hydroelectric power plants (like Project Oued el Melah in the northwest). With a capacity exceeding 1,000 megawatts (according to a study conducted by the Ministry of Agriculture for the country’s 2050 Water Strategic Vision)23, such plants can serve as energy reservoirs, storing electricity when the demand is low, for use when such demand increases (in the summer). This can help reduce recourse to electricity production from natural gas at such times.

Instead of pursuing the illusory prospects of exportation, it is vital to focus on the country’s needs, in both the short and long term: which means meeting the demand for personal and local consumption. This can be done through mobilising Tunisia’s available resources, reviving public investments, and promoting citizen initiatives that involve the collective exploitation of renewable energy projects.

The foregoing suggestions are initial sketches of potential alternatives that Tunisia can pursue. Further details on these alternatives are available in previous publications by the Working Group for Energy Democracy24. Moving forward, the focus will be on practical ways to tackle Tunisia’s energy deficiency and to boost development, especially in historically marginalised regions.

Turning to green hydrogen specifically, the priority here should be to review the National Strategy for the Development of Green Hydrogen and its Derivatives in Tunisia by reference to the national interest and the aim of meeting national demand, rather than following the dictates of foreign agencies whose sole purpose is to protect their countries’ interests. If such a review finds that investing in green hydrogen is indeed a necessity – due to the national interest, prevailing facts and global developments – then a national, comprehensive and multisectoral approach (that goes beyond the vision of just the Ministry of Industry, Energy and Mines) should be applied that will enhance the country’s development.

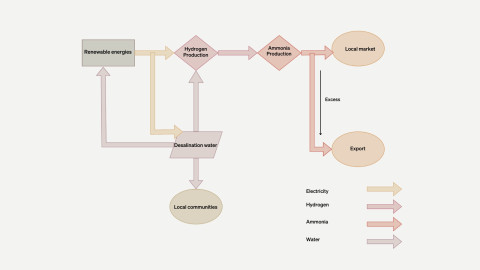

One possible use of green hydrogen produced in Tunisia would be in the manufacture of ammonia, a substance that Tunisia currently imports25, and which is used in the production of fertilisers. This could take place within the framework of a public–public partnership between the Tunisian Chemical Group, the Tunisian Company of Electricity and Gas, and the National Company for the Exploitation and Distribution of Waters. At the level of funding and exploitation, such a partnership could be facilitated by the Ministry of the Environment and the Ministry of State Domains and Land Affairs, under the supervision of the Tunisian Government. As part of this envisaged process, the Tunisian Chemical Group would receive energy (generated through renewable energies) from the Tunisian Company of Electricity and Gas, and desalinated water from the National Company for the Exploitation and Distribution of Waters. Any potential surplus ammonia would be exported.

In regard to the lands used for the production of renewable energies within this process: partnerships could be established with the local populations living on or near these lands, involving them in energy production through new formulas such as cooperatives and community enterprises. Alternatively, local populations could be provided with plots of land for agricultural purposes, alongside receiving desalinated water that will allow them to engage in farming that is aligned with the local climate. Such projects, particularly in the south of the country, would yield economic and developmental returns with a sovereign, national dimension, and would be one way to invest natural resources for the collective interest (Desalination stations could also produce drinking water.) It is hoped that such an approach could keep the so-called Hydrogen Valley26 from becoming an unproductive valley.

The following diagram depicts this potential alternative to the hegemonic and neocolonial projects outlined by the National Strategy.

Figure 4: A national project to produce ‘green’ ammonia through a public–public partnership involving local communities