AI wars in a new age of Great Power rivalry Interview with Tica Font, Centre Delàs d’Estudis per la Pau, Barcelona

Topics

The contest for world hegemony has prompted a global arms race, focused on achieving technological supremacy on the battlefield.

Illustration by Shehzil Malik

How is this new rivalry shaping military spending globally?

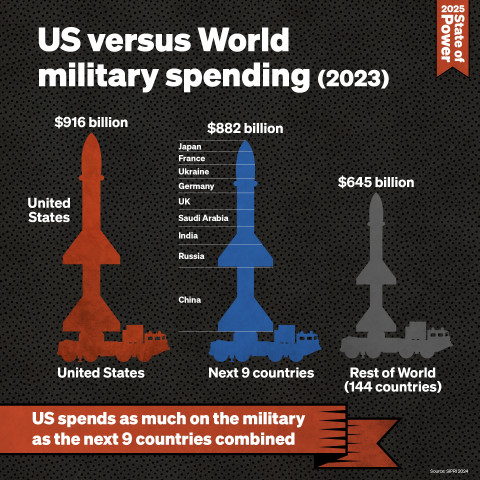

Increased competition for global hegemony, heightened tensions and numerous wars and conflicts have led to a rise in military spending. In 2023, global military expenditure reached a record $2,440 billion, a 6.8% increase from 2022. There had not been such a steep annual rise for more than 15 years.

Source: SIPRI, 2024. https://www.sipri.org/publications/2024/sipri-fact-sheets/trends-world-military-expenditure-2023 https://www.nationalpriorities.org/blog/2024/04/30/us-military-spends-more-next-10-countries-2023/

Military spending has shot up in the US and China, but Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 has also led to a huge rise in military expenditure in various member states of the European Union (EU) as well as other European countries such as Norway and the UK, and also Russia. European governments have fostered fear of a possible Russian invasion of some European country in order to win public support for increases in defence spending.

Military budgets are spent in two main ways. The first is to increase the quantity of conventional armaments such as tanks, missiles or munitions; the second is investment in developing and producing new types of weapons equipped with new technologies or AI. The industrialised countries are racing to develop and acquire these new weapons.

| Year | World Total | USA | EU + UK + Norway | China | Russia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 1,894,251.40 | 772,175.86 | 272,586.11 | 234,421.63 | 75,353.78 |

| 2018 | 1,949,141.27 | 795,416.28 | 279,893.40 | 248,153.16 | 72,514.63 |

| 2019 | 2,023,265.59 | 840,614.81 | 292,349.01 | 260,242.52 | 75,764.91 |

| 2020 | 2,099,061.45 | 880,185.24 | 310,527.81 | 272,509.05 | 77,544.91 |

| 2021 | 2,123,720.29 | 870,751.19 | 319,477.15 | 279,605.78 | 79,081.15 |

| 2022 | 2,201,715.42 | 860,692.20 | 330,572.37 | 291,958.43 | 102,366.64 |

| 2023 | 2,332,719.43 | 880,070.56 | 364,033.13 | 309,484.32 | 126,473.35 |

Source: SIPRI

NATO’s new Strategic Concept updates its deterrence strategy to demonstrate its power to destroy any potential adversary in order to discourage any attack on NATO allies. Its deterrence is based on a mix of nuclear, conventional and missile defence capabilities, complemented by space and cyber capabilities. This focus on deterrence implies accumulating larger quantities of more destructive weaponry.

US analysts have therefore developed scenarios of what a war with China might look like, assuming it could be either a simmering conflict, or victory without a shot being fired or a lightning fait accompli. For each scenario they are convinced that technology will be the deciding factor. Thus researchers from the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) have identified seven critical technologies that could be the key to US success in a war against China. Three of these are ‘sprint’ technologies, in which the advances made by the private sector are not fast enough or not tailored to military interests. These are biotechnology, secure communications networks and quantum computing. The other four are ‘follow’ technologies, in which the private sector is heavily investing and all the public sector has to do is to provide support. These are high-performance batteries, space-based sensors, robotics and AI/machine learning.

NATO allies share the idea that the world is in a new age of disruptive technologies, and have moved to invest in technological innovation and new military capabilities and support for the arms industry to produce them.

What impact has Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and Israel’s war on Gaza had on militarisation, especially in Europe?

At the 2014 NATO summit, during Obama’s presidency, there was tacit agreement that its members would increase their defence budgets to 2% of gross domestic product (GDP), but until recently this had been largely ignored by European Alliance members. At the 2024 NATO summit, the Secretary General Mark Rutte warned that allocating 2% of GDP was not enough and asked citizens to ‘accept to make sacrifices’ such as cuts to their pensions and health and social security systems in order to boost defence spending. He called on the Alliance’s governments to ‘shift to a wartime mindset’.

The EU and its member states are slowly doing this. In 2017 the EU Foreign Affairs Council approved a document setting out the need to launch Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) and agreed the European Defence Action Plan (EDAP), whereby for the first time the EU budget would have an allocation for security and defence. In the same year, the European Council also adopted Decision 2017/971 creating the Military Planning and Conduct Capability (MPCC) within the EU Military Staff (EUMS). The decision establishes a military command and control structure. So, the groundwork for developing and funding a European defence capability was laid in 2017, which has been followed by a series of policies along with the budgets to sustain them.

These include EU policies to: help member states to meet their commitment to increase defence spending, make military expenditure more efficient by promoting joint procurement and purchases, provide credit and financial support for the arms industry and invest in research.

The European Commission has approved the first-ever European Defence Industrial Strategy. This sets several targets: by 2030, 40% of defence equipment should be joint purchases by member states, and the proportion of the defence procurement budget spent on products made by EU industries should be 50% by 2030 and 60% by 2050. In other words, it seeks to ensure that the increase in military expenditure across the 27 EU member states should support European rather than US industries.

To support the arms industry, the EU is seeking to increase credit and to agree multi-year contracts to secure production. It is even considering issuing Eurobonds and modifying the statutes of the European Investment Bank (EIB) so that credit lines can be provided to the arms industry.

Funding for the ‘research window’ on new military capabilities is provided through the European Defence Research Programme (EDRP), whose purpose is to promote new research on innovative security and defence technologies in the areas of electronics, metamaterials, encryption software, and drones or robotics. This funding proposes to finance the defence industry to conduct joint research on innovative technologies, covering up to 100% of direct costs plus 25% towards indirect costs.

As mentioned earlier, NATO's own Secretary General has said that the increase in defence spending must come at the expense of spending on pensions, health and social spending. So we are likely to see social spending either stagnate or decrease, an increase in poverty and a decline in the quality of public services. In short, we may see the dismantling of the welfare wtate that emerged from World War II

What are the new industries – besides the traditional arms firms - that will benefit from this surge in military spending?

We are at the start of a new era, and can already see that there will be considerable funding available for developing products that have a military application. In Ukraine, we’ve also seen civilian companies putting their technologies to military service. US companies such as Capella Space, Maxar Technologies, Microsoft, Palantir, Planet Labs and SpaceX have played an important role by providing the latest technology and cyber support, and have also enabled Ukraine to upload data to the cloud and digitise the battlefield. Let’s look at a few examples.

Ukraine does not have satellites of its own, but it has been able to make use of civilian and military satellite images as well as automated analysis tools, and thus anticipate and block Russian attacks. These images include high-resolution all-weather images from synthetic aperture radars (SAR) from companies such as Maxar in the US or ICEYE in Finland. These images alerted Ukraine to the likelihood of a full-scale Russian invasion in February 2022 by detecting troop movements near the border before the invasion started.

The Meta Constellation tool that Palantir has provided to Ukraine can aggregate data from commercial satellites to create a digital model of battlefields. This system can analyse information from sensors to identify enemy positions, work out which weapons are most suitable for destroying them and assess the damage following an attack, thus improving the reliability and accuracy of forecasts. The US company Primer’s algorithms have been used to capture, transcribe, translate and analyse Russian military communications intercepted from insecure or unencrypted channels.

AI has also been used in Ukraine in drones, kamikaze drones, drone swarms, marauding drones, hypersonic missiles, guided torpedoes and anti-drone systems.

Another type of battlefield is already in raging in the arena of (dis)information, often using civilian technologies. The internet and social media are extensively used to publicise, justify and legitimise actions by particular actors, as well as to win converts to their cause. These media are also used for disinformation campaigns, publishing fake news or distorting the facts, in order to destroy trust in public information and institutions, sow confusion and discredit adversaries and their allies.

These civilian technologies can also be weaponised to disable key infrastructure on which citizens rely. When Russia had just embarked on its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, for example, Apple and Google deactivated the Maps function, which shows road traffic in real time. They also blocked the news channels of Russian media such as Russia Today, Sputnik and others, and withdrew the apps from their app stores. They restricted the ability of Russian banks to make payments. Microsoft has collaborated with the Ukrainian authorities to stop and mitigate cyber-attacks coming from Russia. Just hours before the invasion began, Microsoft’s Threat Intelligence Center detected a new form of ‘malware’, called FoxBlade, aimed at Ukraine’s financial institutions and ministries.

As for the use of AI in weapons systems, Israel has used its extensive database on the Palestinian population to design the Lavender system, which identifies people as members of Hamas or Islamic Jihad and draws up lists of such targets; and the Gospel system, which identifies buildings or other structures from where members of Hamas or Islamic Jihad might be operating. These two systems have played a key role in the unprecedented bombing of Palestinian civilian structures and populations, especially in the first phases of the invasion. Indeed, they had such an influence on military operations that the results produced by the AI system were essentially treated as though they were based on a decision taken by a human being. The military usually only took 20 seconds to authorise the bombing of a target generated by the system, despite knowing that is mistaken in about 10% of cases.

How do you see geopolitics shaping militarisation in the near future?

I see the future as grey. I think tensions will increase between the major global powers and between countries that aspire to become a regional power. In the short term, we can foresee tension related to trade, and tension in supply chains, as US tariffs are introduced alongside a ban on exporting certain high-tech components.

Globalisation involved the creation of lengthy and complex supply chains based only on economic criteria. This entailed major traffic in resources and merchandise, predominantly by sea. Today, half of world trade is directly related to major value chains and it is difficult to find industrial products entirely made in just one territory.

The United States argues that China could weaponise supply chains as it has a huge network of ports all over the world that will assure access to minerals, energy or food. These ports controlled by Chinese state enterprises are also equipped with Chinese cybersurveillance systems. China uses this technology to send information to buyers, sellers, regulators, financial institutions and transport firms. We should recall that China has also laid cables all over the world, so it has no need to use western cables or servers. Added to this is the significant network of ships and containers under Chinese ownership.

In short, ports and maritime transport have become a source of power and conflict: over exports and imports, economic development policies, the transport of merchandise, and the digital information needed to move merchandise through global supply chains.

With the decarbonisation of the economy we will see oil losing geopolitical importance and certain minerals that are essential to the new technologies becoming more important. The European Commission has been working on this: it produced the Critical Raw Materials Act, and in 2020 published an action plan called Critical Raw Materials Resilience: Charting a Path towards greater Security and Sustainability, which seeks to move towards greater ‘strategic autonomy’ in certain minerals. The document lists the critical minerals that will be required, and maps the suppliers of these raw materials and who controls. A report entitled Critical Raw Materials for Strategic Technologies and Sectors in the EU - A Foresight Study was also published in September 2020. It looks at nine technologies considered key for achieving EU targets on climate change and the digital transformation and defines the four key industrial sectors: renewable energy, e-mobility, defence and aerospace.

To conclude, I don’t foresee a war in the classical form of military attacks between the major powers, but rather what is known as ‘grey zone warfare’. This does not involve hybrid acts of war, as there is no direct military confrontation between these powers, although military deterrence will be critical. The clashes will take place by way of large TNCs, which will play a key role and set the political agenda worldwide. Internet companies may come to be seen as ‘a natural resource’ (user data) just as valuable as hydrocarbons and certain minerals, if not more so.

The objectives of these hostile acts will include eroding citizens’ trust in their institutions or corporations, creating distrust in the democratic, political and administrative system, undermining social cohesion or the social models of states and political communities such as the EU or the United Nations, weakening the system of government or public administration so that it has fewer capabilities, and convincing the public – both the target population and the attacker’s own – that the political or corporate system is in decline.

The future is not set in stone, however. Social organisations can and must engage in public debate and push for a change in direction. We may not be able to challenge technological change, but we must speak out if we want technologies to be at the service of life and the common good and to increase human dignity and help to protect the environment.

The EU has defined four industrial sectors as strategic, based on security criteria: transport, renewable energy, the military and space. We will need to engage in debate on questions such as: Whose security? That of the state, of elites, or of citizens? Security against what? What situations do we want to feel safe and protected against?

We will need to focus on the strategic sectors of food, health and the environment as they are critical to sustaining life. It is up to civil society to formulate these questions, identify our priorities and work to make them possible. Social organisations will also need to forge new alliances. The green movement and especially the movements against climate change, the pacifist and feminist movements, and the movements that defend pensions, health or housing must unite in order to fully engage in this new age of technology and militarism.

Other essays

State of Power 2025Read other essays from Geopolitics of Capitalism in State of Power 2025, or explore the full report online here.

-

A fractured world Reflections on power, polarity and polycrisis

Publication date:

-

The new frontline The US-China battle for control of global networks

Publication date:

-

Geopolitics of genocide

Publication date:

-

Building BRICS Challenges and opportunities for South-South collaboration in a multipolar world

Publication date:

-

Can China challenge the US empire?

Publication date:

-

China and the geopolitics of the green transition

Publication date:

-

Beyond Big Tech Geopolitics Moving towards local and people-centred artificial intelligence

Publication date:

-

The emerging sub-imperial role of the United Arab Emirates in Africa

Publication date:

-

A transatlantic bargain Europe’s ultimate submission to US empire

Publication date:

-

In search of alternatives Strategies for social movements to counter imperialism and authoritarianism

Publication date: