A transatlantic bargain Europe’s ultimate submission to US empire

Topics

Regions

Why has the EU remained largely subservient to US interests even when it has not been beneficial to its elites? It is important to explore the structural ties that bind the EU to the US in order to push for a Europe based on principles of solidarity and cooperation rather than competition and exploitation.

Illustration by Shehzil Malik

Post-war finances and how Western Europe and the US became interdependent

US domination in Western Europe dates from the end of World War I (1914-1918), when it played a crucial role in financing the Triple Entente powers, also known as the Allies (Britain, France, and Russia),1,2 shifting the global financial centre from London to New York. By lending $ 1.7 billion to Britain and France, the US established itself as a key economic power.

| Year | Shell Cases (%) | Aeroengines (%) | Grain (%) | Oil (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1914 | 0 | 28 | 65 | 91 |

| 1915 | 49 | 42 | 67 | 92 |

| 1916 | 55 | 26 | 67 | 94 |

| 1917 | 33 | 29 | 62 | 95 |

| 1918 | 22 | 30 | 45 | 97 |

With the end of World War I, the US attempted to disengage from Europe, but then re-entered in 1941 on the side of the Allies in World War II 1939-1945), reinforcing the integration of the US and Western European economies. The Marshall Plan, which began in 1948, signalled a new phase in transatlantic economic integration. This aid programme was intended to counter Soviet influence and promote capitalist and free-trade economics. By injecting significant volumes of financial assistance, the US sought both to reconstruct the post-war European economies and create conditions favourable to its own commercial expansion. By conditioning aid on trade liberalisation, the Marshall Plan excluded alternative development paths for Western Europe and ensured the dominance of US capital. Initially boosting US commercial exports, the Plan later saw US capital focusing on direct investment in European markets.

The Marshall Plan was also a means to push for European integration. Under US influence, France moved away from its anti-German foreign policy, which resulted in its support for the proposed European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), the first step in the process of European integration. Initially, the Marshall Plan had a universalist design that aimed at including the former Soviet Union the global capitalist system. However, as the Cold War intensified, and as it became clear that the Soviet Union would not abandon socialism, this universalist approach was abandoned.3 In the late 1940s and early 1950s, anti-communism became a unifying factor for European and US capital. This process combined maintenance of the status quo in the (former) colonies, to placate colonial powers such as Britain and France, with anti-communism, which was rapidly becoming the main focus of US foreign policy.

Security guarantees and liberal interventionism: NATO

Parallel to economic integration, the US established a new security architecture centred on NATO. Created in 1949, it was essentially anti-communist in its intention, providing security guarantees against the former Soviet Union and a means to maintain the status quo. France was initially sceptical of NATO, and in 1966 withdrew from the NATO Military Command Structure in order to establish its strategic autonomy by developing its own nuclear weapons programme. Although France re-joined the Command Structure in 2009 and carved out its special status within NATO, this did not change the anti-communist security motivations that led to France and other countries across Western Europe to join in the first place.

In 1962, President Kennedy stated that the US ‘does not regard a strong and united Europe as a rival but as a partner. To aid its progress has been the basic object of our foreign policy for 17 years’. NATO became the central institution binding Europe militarily to the US and was not at odds with European integration. This does not mean that there were no tensions within the alliance. The US resisted calls by European allies for greater sharing of responsibilities for nuclear defence, which was precisely one of the reasons that France decided to develop its own nuclear weapons programme. The US was also unhappy with the Ostpolitik of West Germany and France – their policy of seeking to normalise relations with the Soviet bloc. There were also some flashpoints related to decolonisation and the Non-Aligned Movement. The US opposition to the intervention of Britain, France, and Israel during the 1956 Suez Crisis is one such example.

Created during the Cold War, NATO transformed after the collapse of the Soviet Union, becoming a vehicle for the global projection of US power, expanding into Eastern Europe and adopting a broader security agenda regarding transnational threats. As we have seen, NATO was crucial in binding Europe to the US. Bilateral defence agreements between European governments and the US would have amounted to their admission of being US client states. NATO’s multilateral nature allowed European governments be bound to US domination without losing face. NATO thus became a vehicle for the projection of US power across the globe. Throughout this period, France again tried to acquire more strategic autonomy within the alliance, but the US kept a firm hold on the reins.

A constant issue in European–US relations was that NATO’s members should devote more of their gross domestic product (GDP) to defence spending, better known as NATO burden-sharing. With the end of the Cold War, most NATO members significantly reduced their defence budgets as part of the so-called peace dividend. Since EU countries were spending a lower percentage of their GDP than the US on defence, the US government – and the defence industry – believed that they were not paying their fair share. The US started to criticise the EU’s ‘underspending’ on defence under President Obama and this reached a fever pitch under President Trump.

The double shocks of Trump and Brexit

For many decades, Western Europe and the US have seemed committed to securing each other’s leading roles in international affairs, and in their economies, which had become ever more integrated. The 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) illustrated this, as the US sub-prime banking crisis reverberated almost immediately throughout Europe – and beyond – and caused a deep recession in some of the more US-leaning EU economies.4

Militarily, many European states were largely complicit in US actions through their active NATO membership. Notable examples include NATO’s International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), which occupied Afghanistan for 13 years, and the 2011 military intervention in Libya.

US domination over Europe in the military and economic realms seemed secure until 2016, when the combination of the UK’s narrow referendum result to leave the EU – Brexit – and the election of Donald Trump in the US exposed many cracks in European–US relations.

Brexit significantly affected the relationship between the EU and the US, acting as a catalyst for the EU’s pursuit of greater strategic autonomy. While not the sole factor, Brexit, in conjunction with the Trump presidency spurred the EU to reassess its global role and seek greater independence from the US. An important factor was that the UK had been a key intermediary between the US and the EU and before Brexit had played this role especially in negotiations over trade policy and security cooperation.

President Trump’s ‘America First’ agenda viewed both the EU and China as its economic competitors. This led to the 2018 tariffs on aluminium and steel products, which led the EU to retaliate with counter-tariffs. The Trump administration also rendered the World Trade Organization (WTO) dispute-settlement mechanism ineffective just when European countries would have wanted to dispute US tariffs.5 The US also withdrew unilaterally from the Iran nuclear deal and the Paris Agreement on climate change. Both the US and China were already adopting policies that contradicted some of the WTO’s key policies, which were the basis for how the EU has developed. This opened the door for new EU policies, especially concerning state support for corporations in securing raw materials.

In the sphere of security, the US withdrew troops from Germany and Afghanistan without consulting its European allies. It also threatened to pull out of NATO, mainly because the Trump administration believed that the Europeans were not paying their fair share. In 2018 Trump summarised the US position: The United States is paying close to 90% of the costs of protecting Europe. I think that is wonderful. I said to Europe, I said, “folks, NATO is better for you than it is for us.” Believe me. Small countries, big countries, all these countries we are supposed to protect them. I said, “look, it is very simple. You got to pay out. You got to pay your bill."

It is not surprising that after decades of economic integration, the EU would also develop some form of common defence policy. All that was necessary for that to materialise were the right political conditions. The Trump presidency and Brexit created those conditions and motivated the EU to pursue greater strategic autonomy.6 This concept remains poorly defined but can be understood as the EU’s need to develop the military capacity to act independently on the world stage, especially in situations where the interests of the US and the EU diverge. Another factor influencing this search for strategic autonomy was energy. The EU became more dependent on the US for its energy, especially since 2022 when it attempted to end its dependence on Russian gas supplies following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

In the years since Brexit and Trump’s first administration, the EU has made several moves to strengthen its sovereignty, particularly in the areas of security and defence. It has revitalised defence initiatives such as the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO), a treaty-based framework for the 26 participating member states (excluding Malta) to jointly plan, develop, and invest in collaborative capability development and enhance the operational readiness and contribution of the armed forces, and increase defence budgets.7 It also set up the European Defence Fund (EDF) in 2021. With a budget of €8 billion, it marks a significant shift because it enables the EU to directly fund military projects. The European Peace Facility (EPF), which provides funding for military operations and assistance in third countries, was also set up in 2021. It has been criticised as being a disguised subsidy for European arms exports, as it can be used to provide weapons and military training to foreign forces. Finally, the new Directorate-General for Defence Industry and Space (DG DEFIS) in the European Commission was created in 2019 and is responsible for promoting the competitiveness and innovation of the European arms industry.

Defence spending in the EU has risen steadily since 2014 and is expected to hit €326 billion in 2024. The defence industry was ready to profit from this increased spending, often with devastating consequences for people in non-EU countries. A TNI report established a link between weapons sold by European manufacturers and forced displacement in Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Iraq, Nagorno-Karabakh in Azerbaijan, and Syria. In its study of Libya, the Transnational Institute (TNI) found that European weapons are being used both as a means to displace populations and keep them from onward migration to the EU. But it also has major consequences European citizens. The billions of euros spent on defence are therefore not invested in health services, housing, education, infrastructure, and meeting other crucial needs.

Back together and better than ever? China, Ukraine and Gaza

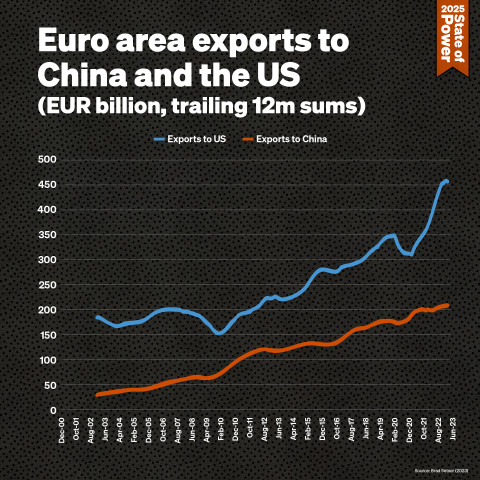

The EU and US economies have become even more integrated since the GFC and are now each other’s most significant trade and investment partners. Transatlantic trade accounted for € 1.2 trillion in 2021, although this is dwarfed by the investment relationship between them. The EU has € 2.1 trillion in outward foreign direct investment (FDI) stock and receives 2.3 trillion in inward FDI stock from the US. Total US investment in the EU is four times larger than its investment in the Asia-Pacific region. EU investments in the US are ten times larger than in India and China together. This translates into substantial affiliate sales – sales by an entity directly or indirectly controlled by a corporation – further consolidating economic interdependence. US foreign affiliate sales amounted to $3.1 trillion in 2021, more than global US exports.

Another important indicator of the interconnected economies is the high level of intra-firm trade. In 2020, 65% of US imports from the EU and UK were intra-firm and there is a similar pattern for exports. This is significantly higher than with other regions and shows the extent to which US and EU companies’ production processes are integrated. This economic intertwinement is the culmination of over half a century of transatlantic integration spurned on by governments of every stripe in both Europe and the US.

This economic integration significantly benefits transnational corporations, which can lobby for more liberalised trade rules, weakened regulations, and preferential access to public funds. Large financial actors, such as major banks and investment funds, also play a major role in shaping financial regulations and benefiting from an integration of financial markets. A clear example of this was ABN AMRO, which was part of an ‘expert group’ that shaped the liberalisation of financial markets. This liberalisation made financial markets in the EU more similar to those in the US, which reinforced integration. This is one of the reasons the GFC had such an impact on both sides of the Atlantic. A similar pattern is seen in the technology sector, where US companies such as Google, Microsoft and Meta (Facebook and WhatsApp) benefit from an EU Digital Markets Act that does not address their control of digital infrastructure and thus does not challenge their position.

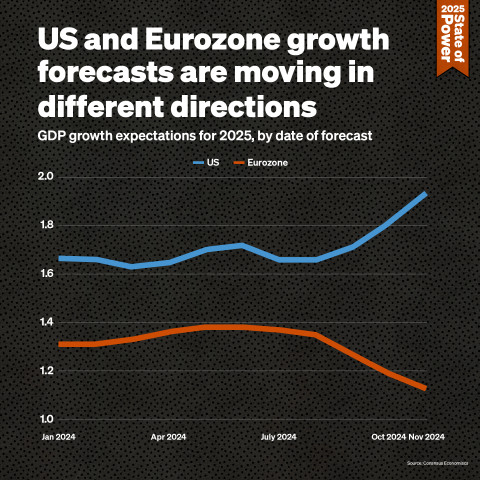

With the Biden administration restoring some normality to the White House after the first Trump presidency came a commitment to repairing the transatlantic relationship and ‘restoring US global leadership’. The hope was that US interventionism, supported by the EU, would once again shape the world according to its interests. However, some of Trump’s legacy remained. The EU continued to attempt to assert its strategic autonomy, while the Biden administration refused to fully repeal the tariffs implemented by the Trump administration, and issues regarding burden-sharing within NATO remained unresolved. Another source of divergence was the position on China. Whereas the US took an increasingly hostile stance, the EU was initially far more cautious in view of its significant economic ties with the country. The EU was generally slower to recover from the COVID-19 crisis than the US and was also hit by an energy crisis following the imposition of further fossil fuel sanctions on Russia after its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

However, as the New Cold War heats up, the EU has moved towards the US position by focusing on de-risking and decoupling from China. This does not benefit capital or working people across the EU as it entails a very complex economic transformation at a time when the effects of COVID-19 and Russia’s continuing war on Ukraine remain unresolved. European participation in the New Cold War is perhaps the best example of continued subservience to the US.

The EU has also continued its aggressive trade policy. Free-trade agreements (FTAs) are in effect neo-colonial arrangements that maintain the dependence of lower-income countries on supplying raw materials. In recent years, this free-trade agenda has been criticised as policymakers on the left highlighted that it often only benefited capital at the expense of the environment and working people. The competition between the US and China has put geopolitics above ideology and meant that the gap between the EU’s preaching of free trade abroad while practicing the opposite at home has become ever more visible. This is most evident in the revived industrial approaches that challenge free-trade dogma and practices. Following the US Inflation Reduction Act, the EU presented its own industrial policy in an attempt to counter US industrial policy. Yet the EU continues to aggresively push for new free trade deals, claiming that they need to be closed for fear of ‘losing’ a region or country to China. Furthermore, given the need for an energy transition, the EU has employed several trade tools to secure critical raw materials.

Russia’s continuing war on Ukraine also increased European dependence on the US, as for many countries it meant a break with the dependence on Russian gas they had developed since the end of the Cold War. Since Germany was among the countries most dependent on Russian gas, the resulting energy crisis sent much of the EU into an economic slump – with the only beneficiaries being companies involved in the infrastructure for liquefied natural gas (LNG).8 Not only did this result in much higher energy bills for citizens across the EU and the UK but it also increased dependence on the US, which became a net energy exporter in 2019. The relatively high price of energy in the EU also helps to explains the different economic performance between many EU member states and the US.

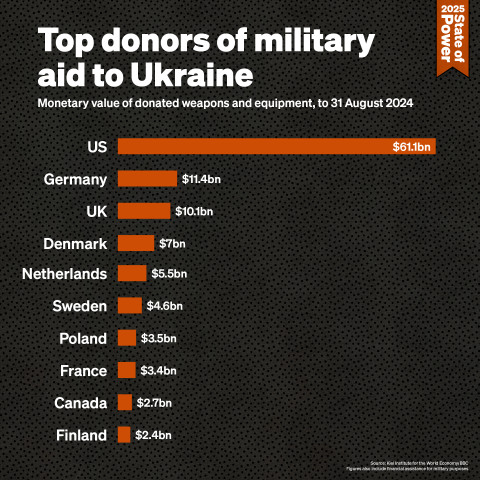

Transatlantic military dependence has also been strengthened in the process. Indeed, Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine might have saved NATO after the mistrust sown under Trump’s first presidency, and certainly aided Europe’s remilitarisation, with most European members of NATO currently spending more than the 2% GDP target on defence. By mid-May 2022, EU member states had announced almost €200 billion in increased military spending for the coming years. This is a bonanza for the military-industrial complexes on both sides of the Atlantic. NATO members have donated over €100 billion in weapons to Ukraine. Moreover, the conflict caused a spike in US arms sales, which in 2023 peaked at $238 billion.

The EU and the US are also complicit in the genocide being perpetrated by Israel in Gaza. While the US provides 65% of all weapons imports to Israel, Germany and Italy have also actively supported Israel with weapons in spite of a majority of their population opposing this. 9 The European Parliament has ritualistically condemned any criticism of unwavering support to Israel and fails to hold the country accountable. The reasons for most European governments’ loyalty to Israel are varied. In Germany, the complex interplay between incomplete denazification in West Germany and the idea of ‘redemption through remembrance’ partially explains why support for Israel was described as the country’s Staatsräson. In countries like Hungary, solidarity between reactionary conservatives and shared Islamophobic values weigh heavier than antisemitism in the bond between Netanyahu and Orban. But a unifying reason is that for the US and most European governments, Israel is a military outpost that, together with Saudi-Arabia and the Gulf monarchies, is crucial for controlling the Middle East, its energy resources, and its shipping lanes. Furthermore, Israeli aggression towards its neighbouring countries represents a boon to their respective military-industrial complexes. This has resulted in €426 million of European taxpayers’ money being used to fund companies arming Israel while members of the Israeli government have been formally accused by the International Criminal Court (ICC) of perpetrating crimes against humanity, war crimes and genocide.

The EU thus seems subservient to US interest even when these are not beneficial to its capital and their political allies. Nowhere is this clearer than in the Netherlands. Even though the US has passed a law to invade The Hague should any US military personnel ever be tried at the ICC or the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the Dutch government seems keen to be the EU member state most loyal to US interests. This means that the Dutch government happily agrees to store US nuclear weapons over which it has no control. This not only cedes Dutch sovereignty, but also makes the air force base at Volkel and the rest of the Netherlands a target for any countries that possess nuclear weapons and decide to deploy them. In a similar case of putting the interests of the US over those of their own citizens, the Dutch government blocked Schiphol Airport from downsizing after being pressured by the US and the European Union, although for years residents of the cities and towns surrounding the airport had demanded it.

Intellectual defeatism and daring to dream of a better future

On both sides of the Atlantic, the centre-left and centre-right have at times become almost indistinguishable in terms of political vision, economic policy and international relations. Both ends of the mainstream spectrum have, since the final years of the Soviet Union and the independence of the former Warsaw Pact countries, emphasised that there is no alternative to liberalisation and marketisation, ensuring the supremacy of private capital. Neoliberal thinking has dominated almost all mainstream political movements ever since.

This encapsulates the intellectual defeatism seen across the political spectrum in the EU, perhaps especially on the left. The European left has traditionally, more than the right, emphasised that a strong social contract with some safety nets is neeeded to address the constant crises of capitalism. Yet across the centre-left, it seems that there is no longer the will to address structural flaws or to dream of a better tomorrow. This is also in part why Western Europe remains in lockstep with the US regarding foreign policy. The Social Democrats were after all the prime architects of Germany’s remilitarisation, a downstream effect of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. On the centre-right, capitalism has never been the subject of real discussion. Liberal and Christian Democrat parties in Western Europe were instrumental in propagating (neo)liberal thought and interventionism.

Recently, the centre-right have tended to become more explicitly nativist and xenophobic. This must also be seen in the context of the rise of the far-right. Neoliberal policies destroyed the welfare state and without it and redistributive policies, liberal and parties drifted farther right. This meant that these liberal parties, such as the VVD in the Netherlands, started to advocate for far-right policies and increased their repressive apparatus that polices working class neighbourhoods and international borders. With liberal parties drawing on far-right policies, the far-right became more mainstream. This has resulted in liberal parties and the far-right joining forces to exclude the left from institutional power. Liberal parties and the far-right have almost the same class politics and, in Western Europe and the US, there is also a high degree of consensus on maintaining US hegemony. The whole political spectrum seems to be moving rightward, with reactionary right-wing politics becoming ever more mainstream.

Some of the core US and European institutions have encouraged such defeatism. The EU and the Maastricht Treaty, for instance, are neoliberal institutions that were designed in opposition to the previous Keynesian, social democratic consensus.10 In relation to foreign policy, thinktanks like the Atlantic Council, the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), and Chatham House in the UK , tend to push the US and EU governments towards a similar foreign policy, their ‘expert opinions’ reinforcing the foreign policy consensus of a Europe that follows the US. Universities have also played an important role in breaking down the old consensus. In the US, Chicago University was the most notorious example but most countries in the EU and UK have at least one university fulfilling a similar role. At the annual meetings of the World Economic Forum in Davos, representatives of these institutions along with corporate leaders meet with politicians, creating a nexus where power and ideas converge. With the demise of the old Keynesian consensus, it has been replaced by a new ostensibly depoliticised consensus that is presented as pragmatic and rational.

There is simply no will and no creativity to imagine a different foreign policy across the political mainstream. European capital has internalised US exceptionalism and fails to or fears imagining a world where the US is no longer the dominant global power. This idea is also influential among citizens in Europe and the US, who see the world as a zero-sum game where they will lose privileges if their global status diminishes. This status quo is partially the result of the participation of European governments in US empire, and the resources and influence that this hands to Europe. With the nomination of Mark Rutte as NATO’s Secretary General, the loyalty of the Netherlands to US empire will be rewarded by hosting the next NATO summit scheduled for 22–25 June 2025 in The Hague.

Herbivores and carnivores

In a 2022 speech made in Madrid, Josep Borrell, Vice President of the European Commission and EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, reacted to the impact of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on Europe. He stressed that the war ‘is an awakening of our initial project, a peace project that put aside the struggle for power and used soft power, trade and law, as our weapons’. He concluded that ‘we must become aware that this is not enough, because we Europeans cannot be herbivores in a world of carnivores’.

Who are these ‘carnivores’ to which Borrell refers? The US and China loom large. With Trump’s second presidency from January 2025, it is by no means certain that the EU will want to hitch itself to an ever more crisis-ridden US global project. Following the dual crises of Brexit and the first Trump presidency, the EU has been increasing its own capabilities as a global actor. But now the dynamic has fundamentally changed. The US focus on Asia leaves the EU to deal with the consequences of US policy in Eastern Europe and the Middle East.

But has this changed the interdependence between the EU and the US? The US–EU trade relationship is the largest of its kind, with transatlantic trade reaching € 1.2 trillion in 2021, making them the world’s two most integrated economies. Joint defence interests are justified by an interventionist bloc organised in NATO and military-industrial complexes on both sides of the Atlantic are currently making record profits through the support for Ukraine against Russian aggression and the genocide in Gaza. Regarding the ‘intellectual defeatism’ of the European political class, politicians at both ends of the political spectrum have failed to paint a new future for Europe. Rather, they have promised a return to a mythologised past, social democratic on the left, and ethnically homogeneous on the right.

For the EU to break with US foreign policy it first needs to have the creativity to shape a new future. This is not a plea for the EU to become a ‘carnivore’. An independent EU policy could be just as damaging as that of the US. Migration ‘deals’ and EU interventions in African countries and around the Mediterranean are evidence of this. The further militarisation will drag it into an arms race that can only produce losers. Rather, the EU should strive to be a force of solidarity, for a foreign policy based on cooperation over competition – which can happen only if it breaks free of its subservience to the US.

Other essays

State of Power 2025Read other essays from Geopolitics of Capitalism in State of Power 2025, or explore the full report online here.

-

A fractured world Reflections on power, polarity and polycrisis

Publication date:

-

The new frontline The US-China battle for control of global networks

Publication date:

-

AI wars in a new age of Great Power rivalry Interview with Tica Font, Centre Delàs d’Estudis per la Pau, Barcelona

Publication date:

-

Geopolitics of genocide

Publication date:

-

Building BRICS Challenges and opportunities for South-South collaboration in a multipolar world

Publication date:

-

Can China challenge the US empire?

Publication date:

-

China and the geopolitics of the green transition

Publication date:

-

Beyond Big Tech Geopolitics Moving towards local and people-centred artificial intelligence

Publication date:

-

The emerging sub-imperial role of the United Arab Emirates in Africa

Publication date:

-

In search of alternatives Strategies for social movements to counter imperialism and authoritarianism

Publication date: