The Limits of Law Why ‘corporate accountability’ will not change the corporation

Temas

Law is fundamentally limited in its potential to challenge corporations' power and their harm, because the law has been created to facilitate capitalist accumulation and therefore the rights of the property-owning class to force others to submit to its will. It cannot, therefore, be expected to have any emancipatory potential.

Autores

From their beginnings three centuries ago, corporations have encountered resistance. As the corporation became the key legal means through which to create and extract profit, this resistance has taken many forms. Enslaved people have led revolts, workers have formed unions, withheld their labour and gone on strike, wildcat strikes have sabotaged the industrial process, reformers have passed legislation to curb the worst abuses, ordinary people have boycotted products, and human rights lawyers have brought cases against companies, mainly in Western countries.

In the last 20 years, legal action and legislation have become the principal means used to establish corporate accountability. Many efforts to bring lawsuits have been made in the hope that judges will recognise corporate complicity in human rights violations and environmental damage, and order reparations. There is also a growing movement seeking a binding treaty on business and human rights.1

Such hopes rest on the belief that it is possible to control corporate activity by legal means. This essay will argue that it is impossible for the law to be the route to achieving justice for victims or democratically controlled corporations, for two main reasons.

First, because capitalism can readily recover from and incorporate or co-opt (legal) claims in a way that both makes it stronger and also disables resistance. Second, and more importantly, because the law and legal systems exist to facilitate capitalism, not to restrain it.

Legal action and legislative reforms are by their very nature unable to address the fundamental parameters of capitalism, and therefore will only ever amount to ‘rearranging the deckchairs on the Titanic’. In order to be effective in fighting against corporate harm, there is a need to move beyond the law, and towards a structurally different system.

In this essay, I highlight some of the legal struggles to achieve corporate accountability and show the limits of using the law to curb corporate power. These limits are rooted in the fundamental nature of corporate capitalism as a legally structured system.

In this context, efforts to achieve corporate accountability in law and governance ultimately serve an ideological function, allowing the effects of corporate capitalism to be seen merely as excesses to be curtailed rather than being inherent in the system. Corporations respond to challenges to their power by foregrounding ‘doing good’, ‘citizenship’ and ‘sustainability’ by presenting themselves as part of the solution – never as part of the problem.

Such moves sustain popular faith in the possibility of eventually achieving corporate accountability – a powerful promise, forever deferred. The world is changing, though, and the cracks in corporate ideology are starting to show. We need to redouble the work needed to come up with new strategies to resist and subvert corporate capitalism beyond making legal challenges to it, and to start imagining, and building, real practical alternatives.

Corporate ideology and the normalisation of corporate power

On the back of British imperialism, the so-called Anglo-Saxon model of the ‘joint stock corporation’ – today best known as the limited liability corporation (LLC or Ltd.) – became the key legal means to facilitate the profit-extracting function of global capitalism. Its main characteristics – since adopted in virtually every jurisdiction worldwide – include the separate legal personality (of the corporation), limited liability (of shareholders for losses incurred by the corporation or company), an indefinite lifespan, and in most countries, the legal obligation to prioritise shareholder returns over everything else (the profit mandate).

Michael Hanke/Commons Wikmedia

Companies are designed to make profits for a limited number of people – their investors), so their purpose has never been primarily to benefit society. They accumulate profit and externalise risk: essentially, a ‘structure of irresponsibility’. The corporate structure has been used to orchestrate, or participate in, some of history’s worst atrocities, including the Great Bengal famine in 1770, the massacres in King Leopold’s Congo2, the enslavement of an estimated 13 million Africans, the holocaust in Europe, military coups across Latin America and the Middle East and elsewhere, as well as environmental destruction on a massive scale. Moreover, corporations are responsible for the relentless exploitation of workers, suppliers and tenants – and, at the other end of the spectrum, consumers – affecting every part of our lives.

Corporations now rule our lives to such an extent that we work for them, shop with them, are treated by them when we are sick, are educated by them, incarcerated by them, and even have our personal and most intimate relations mediated by them through social media and dating apps. With the rapid ‘privatisation’ of every aspect of what we previously understood as public services (and public space) we have come to depend on corporations to an unprecedented degree.

Corporate ideology works to conceal both the corporate legal form and corporate power – in other words, to make us accept the corporation as a natural and inevitable part of our everyday lives and the wider economic landscape. Corporate ideology is the collection of stories that corporations have created to legitimise their existence, form, operations and growth. These stories focus on the importance of corporations for trade and employment, on ‘serving’ a public purpose by pursuing private interest, and of being aware of their ‘social responsibility’. These stories help justify corporations’ ‘rule’, whereby citizens and governments accept corporate power.

The main achievement of corporate ideology has been to frame any kind of violation as ‘corporate excess’ rather than as a result of something inherent in the corporate form, and in the legally structured corporate capitalist system, as such. This means we are kept busy seeking to limit and control such corporate excess, and thus fighting the symptoms rather than the disease itself. We mop the floor, but we don’t turn off the tap. Much work goes into advocating for, creating, and strengthening such control mechanisms. Better mops mean less flooding, and corporations manage to make the taps look inevitable, normal, and ‘here to stay’.

We can see the effects of these contradictions when we scrutinise legal reforms and legal actions, whether in the form of ‘legalised Corporate Social Responsibility’ measures or litigation to seek corporate accountability. Such work – which can have meaningful positive effects, also has the very real potential to exacerbate the racializing and class-based oppression inherent in capitalism.

These tendencies are the warning signs that should alert us to the limits of using legal means to restrict corporate power, and cause us to consider the deeper, fundamentally symbiotic, facilitative relationship between law and capitalism. Law and capital are two sides of the same coin, and taken as a whole, and despite small victories and some positive effects, corporate legal accountability is an illusion: legal systems cannot but generate capitalism-compliant outcomes.3

Corporate Social Responsibility and the move to ‘legalise CSR’

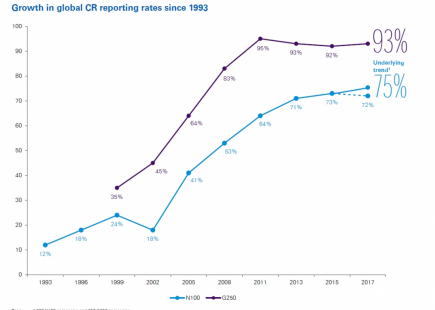

The Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) industry and proposals for corporate legal accountability are expressions of corporate ideology created in response to the backlash against the legitimacy of the corporate form and profit-making activities.

Corporate Social Responsibility – and its younger sibling, ‘Corporate Citizenship’ (CC) – have in recent years lost much of their ideological purchase, however, and are frequently exposed as whitewashing or greenwashing efforts. While there may be concrete local benefits from schools and clinics built by corporates in remote areas (and there are real reasons for non-governmental organisations (NGOs) or indeed Market-NGOs (MaNGOs)4 to support such programmes), activists and corporate strategists alike largely recognise that CSR and CC are regimes of corporate ideology designed to make (mainly Western) consumers (and, to a lesser extent, institutional investors) feel better about buying their products or services.

While the adoption of non-binding CSR ‘commitments’ may have marginally improved corporate behaviour, it is also clear that CSR does not fundamentally change the parameters within which companies operate. For instance, BP’s massive ‘green’ makeover did not bring an end to environmental controversy or change its economic model built on destroying the Earth’s climate. This is because CSR does not fundamentally alter the fact that corporate directors are bound (by law in most countries) to serve the financial interests of shareholders over all others. Corporations can only ‘do good’ if this translates into shareholder returns.

One of the main problems that progressive business and human rights activists therefore see with CSR and regimes such as the United Nations Guiding Principles (UNGPs), developed by Professor John Ruggie, is that they are not enforceable; they have no ‘teeth’. It is too easy for corporations to pledge allegiance to them in principle and then ‘forget’ all about them in practice.

Moreover, if companies do ‘forget’, there is no appropriate forum (other than the media) to hold them to account for failing to live up to their promises. This – and charges of ‘corporate impunity’ following several corporate scandals in recent years – has given rise to a move to ‘legalise CSR’, and to create binding legal rules and enforcement mechanisms and instruments. Frustrated with what they perceive as CSR’s ‘lack of teeth’, activists have moved in two main directions.

One direction being taken by progressive NGOs, social movements and human rights lawyers is the push to ‘legalise CSR’ by encouraging states and the international community to adopt binding instruments setting out corporate obligations with regard to human rights and the environment. One such movement is the push for legislation on the transparency of supply chains, such as France and the US state of California have recently enacted, or for binding human rights ‘due diligence’ requirements. At the international level, the main efforts to legalise CSR globally are led by a movement that is currently working with the United Nations Human Rights Council on a binding ‘Business and Human Rights Treaty’.

The other main direction has been led by business and human rights (BHR) lawyers, who have engaged in increasingly creative litigation in order to seek the enforcement of human rights and environmental principles via the courts. These include examples such as the Urgenda case, in which a Dutch court condemned the Dutch government for its failure to protect public health by failing to curb climate change. They also include other civil and criminal claims and complaints filed with various regulatory and judicial bodies.

Best known of these are the compensation suits brought against corporations (usually as legal persons, sometimes in conjunction with key corporate officers) under the Alien Tort Statute (ATS) and other provisions of US law, which have been numerous and highly publicised. The latest form of ‘weaponised CSR’ involves filing complaints at the International Criminal Court (ICC) against corporate actors. There are also many local and national campaigns to sue and prosecute corporate actors that have not been so highly publicised.

The dark side of (legal) corporate accountability struggles

The efforts to achieve corporate accountability discussed above – voluntary CSR, legalised CSR and BHR litigation – have had many positive effects, not least the vastly greater public awareness of corporate activities worldwide. Litigation often involves courts forcing companies to disclose details of their operations that were not previously in the public domain. This (negative) publicity may result in corporations losing potential contracts or customers and thus generate a financial incentive to change their operations.

Corporate accountability campaigns stimulate public debates and discussions that were not taking place before, and educate the general public as well as policy-makers. Moreover, the collaboration between communities and progressive lawyers during the time it may take to prepare a case or a campaign can be empowering in itself. The movement for a binding Business and Human Rights Treaty, for example, has brought together social movements from various parts of the world, and generated knowledge-sharing and empowerment on other issues well beyond the main campaign.

Nevertheless, counter-intuitively and despite activists’ best efforts, these strategies suffer the same defects as other legal strategies, in that they fail to challenge the corporate structure of irresponsibility in and of itself, as well as the broader system of corporate capitalism. In addition, these strategies play into the inherent dynamics of capitalism that unequally distribute violence along gendered, racialised and class lines at the global level.

These are not just the ‘side effects’ of legal corporate accountability methods, but reveal them as part of the problem. They show that even when one makes a pragmatic choice to engage in reformist work, capital will manage to co-opt or sabotage any progressive intentions to its own ends. Ultimately, rather than tipping the balance in favour of gradual improvement, such legal methods will be follow the capitalist logic and create a ‘market for responsibility’ – whereby responsibility is commodified, and harm is paid off. Human rights work, therefore, becomes part of the problem.5

Compliance and Class

When legal systems focus on corporations, they overwhelmingly seek to achieve compliance rather than to prioritise enforcement and punishment. Compliance focuses on incentivising actors to comply with particular rules rather than on sanctioning transgressions. This differential treatment – if you compare business with ordinary individuals accused of a crime – is the result of the economic power of business and the common class interest of business and the legal and political elites.

When activists express concern that CSR rules have no teeth, it is worth noting that the difference between existing voluntary and any new legally binding norms in a compliance-focused approach is likely to be semantic. Legally binding rules in a compliance model do have teeth, but they aren’t used. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Guidelines illustrate a compliance model.

So, when the international NGO Global Witness lodged an official complaint under OECD Guidelines against mining company, Afrimex’s trade in minerals that had contributed directly to the brutal conflict and large-scale human rights abuses in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), the company, by promising to adopt a CSR policy document, avoided being sanctioned after a finding of violation of the Guidelines.6 Like voluntary guidelines, compliance-based approaches seek to achieve adherence to rules through persuasion and incentives rather than by the threat of enforcement. At the same time, the mere existence of binding CSR rules, in combination with a ‘compliance culture’, has the power to deflate the charge of ‘corporate impunity’. ‘Something is being done’, after all.

Given that the UNGPs follow a compliance model, it is likely that domestic-level ‘legalised CSR’ laws implementing them would do likewise. The UN Special Rapporteur on Business and Human Rights has defined the ‘responsibility to respect’ human rights as ‘in essence mean[ing] to act with due diligence to avoid infringing on the rights of others’.7 ‘Due diligence’ here means to show efforts towards achieving compliance. There are currently high hopes that several countries, and possibly the European Union (EU), will adopt mandatory Human Rights Due Diligence laws.8

The trouble is that building and invoking a compliance culture in which all employees exercise due diligence has two main effects that undermine its potential for achieving justice.

The first is that a corporation can shield itself from liability by adopting programmes that provide compliance in technical terms while not actually reducing the incidence of ‘violation’. If a company is charged with failure to exercise due diligence, a so-called ‘due diligence defence’ can then be invoked, which allows the company to argue that managers had followed protocol.

The second is that it has a class-based effect as it can shift blame from directors and managers to the workers. This is because due diligence in a corporate compliance programme works through the senior manager’s delegation of responsibility, in which all employees have a specific task list, receive training on compliance, and have to sign off on the accomplishment of their tasks. Essentially, aberrant outcomes are considered to be the result of workers’ deviation from the norms.

This means that, even in countries that have enacted a corporate criminal law, the most likely target of enforcement action (if any) is a low-ranking individual employee. As such, ‘legal’ corporate responsibility immunises the corporation itself.

The same process can of course be replicated internationally. Lead firms ‘delegate’ responsibility for certain issues to suppliers – an issue which campaigns and legislation on supply chain transparency and liability seek to counteract9 – but which the certification industry compounds.10 Compliance, especially when it is strengthened by an inspection and certification scheme, avoids top-level responsibility. For instance, it allows corporations to require low-level managers not to overwork their subordinates, while setting quotas that cannot be met without enforced overtime. An excruciating example of this was revealed in the ATS litigation against Firestone’s operating rubber plantations in Liberia. Their daily quotas for tappers were so high that to avoid being sacked, adult workers had no choice but to bring their children to work.11

At the same time, it is very hard for outsiders to investigate such claims because only someone who thoroughly understands a specific business could tell whether such quotas were unrealistic. Researchers from the Sheffield Political Economy Research Institute (SPERI) at the University of Sheffield in the UK have found that compliance audits – including those on supply chain transparency – reinforce the labour and environmental problems that NGOs are striving to improve. They conclude, ‘The audit regime, with the involvement and support of NGOs, is reducing the role of states in regulating corporate behaviour and re-orientating global corporate governance towards the interests of private business and away from social goods’.12

In the unlikely scenario that a court of law does manage to enforce a legalised CSR norm on a company (such as a new regulation on health and safety), a financial penalty or revocation of a licence to operate are not incurred by those most responsible at the top of the company. Rather, they are paid by increasing the cost to the consumer of purchasing its products or services; cutting the workforce or reducing their pay or conditions; or slashing expenditure in other areas, possibly including measures to reduce the corporation’s negative environmental impact. This means that punishment of the corporation is ‘socialised’ like any other risk, and can lead to the (collective) punishment of workers. Back in 1970, Ralph Nader famously described how corporations can, and often do, opt to pay a fine rather than adopt technology to conform to safety or environmental regulations if to do so is costlier.13

Rather than constraining corporate capitalism, then, measures such as compliance that aim to achieve corporate accountability, serve to maintain and reproduce – with renewed legitimacy – the profit-extracting rationale of the corporation and corporate capitalism, while the burden of compliance is disproportionately borne by workers and the environment.

Enforcement and imperialism

Most business and human rights (BHR) litigation takes place in Western jurisdictions – often in the corporates’ home country – but focuses on corporate violations in countries in the Global South. This is for two main reasons. First, the mostly low-level corporate violations in the home country remain invisible or appear normal; and second, that many ‘cause lawyers’ are often NGOs receiving development aid to assist countries in the Global South. The language used by many of these lawyers reveals the inherent imperialist nature of such activity.

Suing companies in countries in the Global North for their actions in the Global South is described by ‘experts’ as ‘necessary’ because low-income countries with ‘underdeveloped legal systems’ are simply not able to draft and enforce their own legislation to regulate corporate behaviour. In addition, in the Global North it is commonly held that such countries tend to have ‘oppressive leaders’, making it even more necessary for multinationals headquartered in the Global North (voluntarily) to set standards of good behaviour. We can easily recognise this as continuing a pattern of racist, neo-colonial thinking and behaviour.

It is well known that the shift of most manufacturing and extractive industries to the Global South suits business because they incur lower costs and can make ‘crimes’ less visible to their end consumers. With increased public scrutiny, however, there is a real risk of brand-name damage as a result of a ‘scandal’. Corporate ideology ensures that the blame for scandals is attributed to ‘badly chosen’ sub-contractors rather than a result of power relations down the supply chain and of price squeezing. Moreover, as we saw in the case of the Rana Plaza disaster in Bangladesh, lead companies can deny all knowledge of an ‘illegal sub-contract’ with a local firm.

Thus, BHR litigation can serve to create a distinction between ‘civilised’ multinational corporations (MNCs) based in the Global North on the one hand, and ‘cowboy’ companies in the host state on the other. Legalised CSR creates the possibility (or threat) of selective enforcement against ‘uncivilised’ corporations, to ‘level the playing field’,14 and to ensure their bad reputation does not affect all corporations.

An example of potentially ‘imperialist human rights litigation’ could be the recent case brought against tech giants including Apple, Google and Microsoft for the maiming and deaths of child labourers in cobalt mines in DRC. This class-action law suit concerns the (mainly) African context of conflict-related resources.15 This could become the paragon of the pro-business use of corporate accountability law, if it activates proposals aimed at regulating the market for natural resources in conflict-affected parts of the African continent in order to facilitate the prosecution of ‘rogue’ traders and ‘artisanal’ miners connected to armed groups – thus enabling international corporations to mine and trade without the risk of being stuck with the (costly) ‘conflict mineral’ or ‘child labour’ labels.16

Julian Harneis/Flickr Child Mining in Congo (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/)

‘Cause lawyers’ as the reproduction of white privilege

The romantic ideal of the civil rights movement, of ‘little people and landmark decisions’17, of ‘speaking law to power’, has led some lawyers to invoke traditionally statist claims for order and control through criminal law. International criminal law prosecutions in the early 2000s, operating under the doctrine of universal jurisdiction (which holds that certain very grave crimes can be prosecuted in any country regardless of where they were committed and by whom), is a prime example, but this trend is spilling over to BHR legal cases, as we have seen in the complaints against corporations filed with the ICC, such as the submission by the Global Legal Action Network (GLAN) against Australia’s network of offshore migrant detention centres. These legal actions could be seen as a form of resistance or class struggle, as tactical ‘principled opportunism’18 that may be successful when it coincides with ‘judicial activism’.19

This type of legal action on corporate accountability, however, ‘lifts’ corporate behaviour out of local (usually low-income country) jurisdictions and potential local control (the location of the harm and the people affected by it) into the Western-controlled sphere of international law.

BHR lawyers in such cases create a relation between someone who becomes ‘the victim’ and the corporation. The role of lawyers in persuading people to bring cases in Western jurisdictions is in some way the equivalent of ‘spreading capitalist law’ (as part of the civilising or capitalising mission) as the corporate colonisers did in the nineteenth century. In order for a claim to be valid and recognised, human beings must become legal subjects, articulate their needs, grievances and wishes in legal vocabulary and in a foreign (usually Western) courtroom, through (usually) a white male lawyer. They must ‘join the system’ in the same way that ‘decolonised’ peoples had to join the Western state system and European international law.

As a Western BHR lawyer, I may believe I am the enabler, the empowering medium in this equation, but in fact produce (constitute) the ‘victims’20 and demand their surrender to my expertise. I then become a rights-entrepreneur, claiming to speak for the oppressed, for justice, but in reality speaking as the enforcer of capitalism. Thus, unwittingly, BHR lawyers create value for the corporation/corporate capitalism – extracted from those on whom the suffering has been inflicted as well as (often) the natural environment – with the ‘victims’ barely ‘compensated’, if at all. We may wish to see an MNC hung out to dry in court, but it is not going to happen, not even ‘one day’, the legal-capitalist system will not allow it.

Law and capital: creating a market for responsibility

Through Western corporate accountability ‘cause lawyers’, the affected individuals (usually in the Global South) are labelled as victims in a legal relationship in which they are treated as formal equals with the corporation – a relationship that erases the obvious inequalities of power between the parties. Here the victims must negotiate the ‘price’ of the harm done to them.21 The corporate decision-maker gets to calculate the benefit of the violation (e.g. conflict diamonds are likely to be cheaper than ‘clean’ diamonds) and the likely outcomes of any legal process to determine whether to come to an eventual settlement.

There are many factors at play that shape that decision – the chance that those affected will speak out or find (or be found by) a human rights organisation or UN-appointed expert, the chance that they will commence litigation, the chance a court will keep the case going for a few years while the human rights NGO publicises the issue, the expected drop in sales and or share price, and legal fees. The decision on whether to cause the harm has a calculable price tag. For the ‘victim’, the need and wish to be free of injury becomes a ‘right’ which can be worth investing in through, for example, lawyers’ fees and time away from regular productive labour, in return for a calculable chance of success. What is my price, for what sum will I relinquish all further claims?

It makes sense to ask why businesses (such as Shell facing the litigation by Ogoni in US courts) would settle such cases if the record shows that the likelihood of the petitioners winning in court is next to nil. The reason is that even if they pay, such settlements are beneficial to the corporation as it allows it to look generous and recover from bad press, as well as to get claimants to sign statements relinquishing future claims. Most importantly, as the human rights lawyer Michael Sfard argues in a comparable context, it ‘supplies the oxygen’ of the system itself, helping to render it sustainable and legitimate.22

Such corporate accountability cases, therefore, turn the ‘crime’ from a problem that concerns international society into a problem between the individual victim (or group) and a powerful ‘fictional’ economic entity in a powerful state. This makes it a quantifiable problem if it is ‘settled’ or the company receives a financial penalty.23 In December 2011, Trafigura, for example, was convicted in a Dutch court of concealing the dangerous nature of the waste aboard the Probo Koala ship. The company’s fine was reduced by the court to €1m because the company had set up a compensation fund for victims.24 This ‘solution’ serves to take the ‘victim’ out of the picture as an agent and merely positions her as a recipient of goodwill gestures from the corporation.25

Christian Aslund, Greenpeace

Subsequent cases, filed in France, The Netherlands and the UK, seeking compensation for the harm to thousands of citizens of Côte d’Ivoire affected by toxic waste dumped from Trafigura’s ship, led to dismissals and out-of-court settlements.26 The affected individuals are forced to sell their right to remain free from harm. I say ‘forced’, because the situation is comparable to ‘free’ labour – it may be necessary for survival just as any worker in a low-income job cannot walk out of a situation where their rights are abused. As such, the rights vs crimes paradigm is uniquely neoliberal: it is each individual’s own responsibility to ‘valorise’ or to claim (negotiate, exchange) her right: claim your prize! Responsibility for violating a right (causing harm) exists only insofar as (and to the value of) the right that is claimed.

The result of legalised CSR thus supports the corporate ideology of ‘canned morality’ – the dispensing of commodified moral disapproval in order to conceal the corporate structure and its broader effects on society and the natural environment. The most important transaction is paying off the existing or potential victims and placing them in a relation of exchange, which results in a return to a balanced account, and to innocence. Thus, liability is socialised and the corporation legitimised.

The above examples show that while we may seek to improve legal instruments, or arguments, the underlying reason for the failure to curb corporate harm is not the lack of law but law itself. Capitalism is ‘baked into’ law and the law lies at the origin of capitalist accumulation – most of all the core norm of private property, which permits exchange in the market, and is inherently violent and hierarchical as it includes the right to exclude others from ‘my’ property. Contract law, criminal law and trade law, and company law, exist to protect private property rights and capitalist accumulation – and therefore the rights of the property-owning class to force others to submit to its will. It cannot, therefore, be expected to have any emancipatory potential.

Building Counterpower and Alternatives

The broader danger of focusing on legal accountability mechanisms is that it absorbs both a critique of capitalism as well as grassroots anti-capitalist resistance. It replaces them with a struggle in which the inherent violence of capitalism is reduced to ‘corporate wrongdoing’ and an illusion whereby, once there are accountability mechanisms in place, the corporation and thus capitalism can be ‘fixed’.

What we need is to redirect that energy, skill and commitment to a better world into strategies of resistance against corporate power that transcend reformism. We can look at the pre-figurative power of cooperatives as alternatives to for-profit corporations, to tactics of strike, sabotage and more generally labour struggles in the changing economy. We can learn from movements such as Cooperation Jackson in Mississippi – and similar ones around the world – seeking to transform their productive economy from the ground up – for direct pointers on how (not) to strive for another world beyond corporate capitalism. To transcend corporate capitalism, we must scale up existing collective counter-power and, en masse, build viable long-term models of production that provide for daily needs and do not rely on extracting surplus profit for the few.

We might ask why we cannot do both – continue reformist work while also building alternatives. The first reason is that, as shown above, efforts to achieve corporate accountability supply oxygen to capitalism, make it seem legitimate, inevitable, and largely under control. Such efforts often end up being co-opted or subverted, and become ineffective at best, or at worst counterproductive. Most of all they sustain a system that harms the poorest, racialised and gendered people of the Global South, and which currently threatens the survival of the human race and of all species.

The world is in a state of flux, and there is greater awareness than ever before of the nature and form of corporate power, and the suffering that it causes to workers and to the environment. Most would now agree that it is beyond the capability of states to regulate corporate power, and many would recognise that state and corporate elites are just not interested in change. At the same time, labour and social justice activists are realising that the old methods of advocacy and campaigning are not sufficient. We cannot dismantle the master’s house by using the master’s tools, however much we hope we can. New ways to resist are emerging and old forms of struggle against corporate capitalism are making a come-back. We are going to need all the imagination, creativity, courage we can muster to fight for a world that can survive beyond tomorrow.

TNI is keen to promote debate and discussion among progressive movements on critical issues and are glad to include this essay on the important question of what mechanisms can best control, transform or replace the corporation. In State of Power 2020, we also have essays by Adoración Guamán and Brid Brennan/Gonzalo Berrón arguing in support of using international human rights law as part of a broader strategy of mobilisation and struggle to address corporate impunity and access to justice for affected communities. Let us know what you think!

Notes

1 For the full argument see Baars, G. (2019) The Corporation, Law and Capitalism: A Radical Perspective on the Role of Law in the Global Political Economy. Leiden: Brill, and for a shorter version Baars, G. (2016) ‘It’s not me, it’s the corporation’: the value of corporate accountability in the global political economy’. London Review of International Law, 4(1). This essay draws closely on these works.

2 Leopold II of Belgium (1835–1909), who created and was the sole owner of Congo Free State (now DRC), and inflicted unspeakable cruelty on native peoples he forced to work in the rubber industry, inspiring Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1902).

3 See Baars (2019) and also, Miéville, C.: Between Equal Rights: A Marxist Theory of International Law, Pluto Press, 2006.

4 See Shamir, R. (2004) ‘The de-radicalization of Corporate Social Responsibility’. Critical Sociology, 30(3), 669–689; see also: Shamir, R. (2008).’The age of responsibilization: On market-embedded morality. Economy and Society, 37 (1): 1–19.

5 Kennedy, D. (2005) The Dark Sides of Virtue: Reassessing International Humanitarianism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

6 Final Statement by the UK National Contact Point for the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises: Afrimex (UK) Ltd.

7 Report of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on the issue of human rights and transnational corporations and other business enterprises, 22 April 2009 (UN Doc. A/HRC/11/12)page 2

8 https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/mandatory-due-diligence

9 See, for example, the recent French laws

10 http://speri.dept.shef.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Global-Brief-1-Ethical-Audits-and-the-Supply-Chains-of-Global-Corporations.pdf

11 https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/firestone-lawsuit-re-liberia-0

12 http://speri.dept.shef.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Global-Brief-1-Ethical-Audits-and-the-Supply-Chains-of-Global-Corporations.pdf

13 Ralph Nader (1965) Unsafe at Any Speed: The Designed-In Dangers of the American Automobile. New York: Grossman Publishers.

14 Traidcraft refers to ‘cowboys’ who ‘act … as if they are above the law’ and ‘[i]n doing so … also damage the reputation of responsible British companies’, echoing David Cameron’s 2013 speech to the World Economic Forum. Traidcraft (2015) Above the Law: Time to hold irresponsible companies to account, 27 November.

15 https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/usa-apple-google-dell-microsoft-tesla-face-lawsuit-over-forced-child-labour-in-drc-cobalt-mines

16 See https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/glencore-congo-cobalt-mining-lawsuit/45446800

17 Raz, H. (2008) ‘Of Little People and Landmark Decisions’, Haaretz, 28 November. The subtitle reads, ‘Sometimes all it takes to right a wrong is for one person to stand up and make his or her voice heard’. See

18 See Knox R., (2009) ‘Marxism, international law, and political strategy’ , 22 Leiden Journal of International Law, p. 413.

19 See Marks, S. (2007) ‘International judicial activism and the commodity-form theory of international law’, European Journal of International Law, 18(1), p. 199.

20 Madlingozi, T. (2010) ‘On Transitional justice entrepreneurs and the production of victims’. Journal of Human Rights Practice 2(2) p. 208.

21 An example is Shell’s activities in the Ogoni Valley in Nigeria: Shell has already agreed a number of compensation deals with those affected, yet continues its activities with the same claimed effect on local communities. For another example, see Day, Leigh (2015) ‘Shell agrees £55m compensation deal for Niger Delta community’, 7 January; and Day, Leigh (2016) ‘40,000 Nigerians take Shell to the UK High Court following oil spills’, 21 November.

22 Sfard, M. (2009) ‘The price of internal legal opposition of human rights abuses’. Journal of International Criminal Justice 1(1), p. 45 by analogy.

23 For the current ‘enforcers’ such as CCR and other private cause lawyers, it is not financially feasible to file criminal cases (aside from whether criminal cases can be brought/initiated by private parties) because they normally also rely on settlement deals for their own funding.

24 Trafigura, LJN: BU9237, Gerechtshof Amsterdam, 23 December 2011, Case No. 23-003334-10.

25 Shamir, R. (2010) ‘Capitalism, governance and authority: The case of Corporate Social Responsibility’. Annual Review of Law and Social Sciences (6), pp. 531⎼53.

26 ‘Trafigura lawsuits (re Côte d’Ivoire)’, Business and Human Rights Resource Centre; ‘Ivory Coast Toxic Waste Victims Still Await Payments’, VOANEWS, 12 November 2015.