Over the past years, migration has been increasingly at the center of national and international tragedies, from the thousands of Rohingya fleeing persecution in Myanmar to West African migrants being sold at auction by smugglers in Libya, or migrants’ children being separated from their parents at the Mexico border in the United States.

Beyond the intermittent media focus on these tragedies, migration is far from being a new phenomenon. Today, an estimated 250 million people around the world live in a country different from their place of birth. According to the United Nations High-Commissioner from refugees, more people were forcibly displaced around the world in 2017 than ever before. And this trend is not going to reverse. In the next couple of decades, movements of people are expected to keep increasing, caused by a variety of factors, not least climate change.

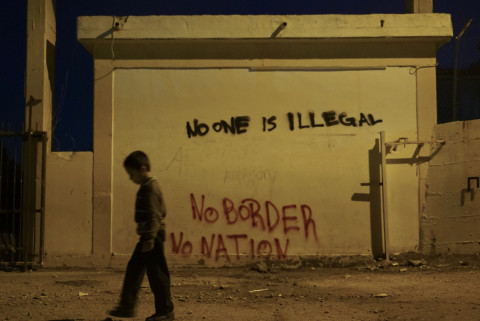

Yet, State’s reaction to migration has often been driven by distrust, nationalism, or xenophobia. People on the move are frequently used as scapegoats by political leaders who blame them for economic and social problems. As a result, migration has essentially been framed as a national security issue, leading to the militarisation of border control, strict visa requirement policies and increased surveillance, criminalisation and detention of migrants. Movements of people have recently been reduced to a « migration crisis », calling for emergency and extraordinary measures.

This environment is key to understand not only the threats faced by people on the move, but also by those who act to defend their rights. Earlier this year, I decided to dedicate my report to the UN Human Rights Council to those human rights defenders. I have chosen to use the expression « people on the move » to include, without distinction, documented and undocumented migrants, asylum seekers, refugees or migrant workers, internationally and internally displaced people.

The countless people who act to defend the rights of people on the move often come from very different backgrounds. Many of them decided to act out of solidarity and humanity, as a spontaneous reaction to the suffering and despair of newcomers. Some also see their actions as a way to alleviate the indifference or cynicism of public authorities. They give tea and biscuits to a family sleeping in their street. They give them shelter for a night. They help them charge their phone. They give them a ride on a very cold day. They try to grasp their own country’s immigration law to help them seek asylum.

For doing so, many face intimidations, threats, arbitrary arrest and judicial harassment.

We live in a time when people are being criminalised for helping those in need. In many parts of the world, including in Europe, assisting undocumented migrants is a criminal offence, and the law fails to clearly articulate humanitarian exceptions. This is, at times, part of a more general trend of increased pressure over civil society, like in Hungary, where the law known as « Stop Soros » has been issued along with other measures aimed at obstructing the work of human rights organisations. But it goes well beyond that.

Some human rights defenders are being charged with smuggling or human trafficking after saving the lives of migrants at sea or at the border, and bringing them to a safe place. The actions of NGOs rescuing migrants at sea have been obstructed in plenty of ways, including attacks by extremists, port authorities seising their ships, and smuggling charges brought against their staff. Helena Maleno, a Spanish activist, has been judicially harassed because of phone calls she made to request assistance for drifting vessels off the coast of Morocco.

Other human rights defenders are being accused of defamation because they have voiced concern and drawn attention to abuses committed by the police, or by private companies managing detention facilities. In some countries such as Australia, human rights defenders hardly dare to speak out at all about these abuses: the laws makes it a criminal offence to disclose certain protected information, which dissuades anyone from sharing information about human rights violations committed in off-shore detention centers. Advocating for the rights of people on the move has, to many extents, become perilous.

Even when only applied sporadically, all these criminal provisions have a chilling effect on civil society. They instill fear and intolerance. They stigmatize people on the move, and the human rights defenders who seek to help them, as criminals. They incite everyone to turn a blind eye on violations, instead of encouraging the protection and promotion of human rights.

Those who suffer the most from this hostile environment are people on the move. Many of them are human rights defenders themselves: many refugees have to leave their countries due to the threats and persecution they underwent precisely because of their actions in favour of human rights.

Yet, because of their precarious administrative situation, it is often excessively difficult for migrants to defend their own rights and the rights of others. They fear being deported if they complain about human rights violations committed by the authorities. They fear being arrested if they dare to protest through peaceful assembly. They risk losing their job - and many times their residence permit - if they report their employer’s abuses, when local labour laws recognise their rights at all.