Smoke Screen How states are using the war in Ukraine to drive a new arms race

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, western governments have pledged unprecedented financial support to militarism, citing the threat posed by the war as justification. Political leaders have repeatedly deemed this response to be reasonable, proportionate, and necessary to support Ukraine’s war effort and to deter Russia from advancing further westward.

Downloads

About smoke screen

Authors

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, western governments have pledged unprecedented financial support to militarism, citing the threat posed by the war as justification. Political leaders have repeatedly deemed this response to be reasonable, proportionate, and necessary to support Ukraine’s war effort and to deter Russia from advancing further westward. As well as sending weapons to Ukraine, states have simultaneously used the war as a smoke screen to justify replenishing, expanding and modernising their own stockpiles of armament and to bend and reshape existing arms trade regulations. This is driving unbridled militarism and a new arms race.

The rationale used to justify increased military spending and the stockpiling of arms is that this is necessary to boost defence capacity, which in turn makes us safer. It completely overlooks the fact that western nations are already extremely over-armed. If we interrogate the claim that militarism makes us safer, we will find that it is far more likely to stoke tension and fear, generate instability and insecurity, to provoke and prolong armed conflict, and to fuel current and future wars.

Furthermore, vast sums that could otherwise be invested in health, education, and other essential social services, as well as to offset the consequences of global heating and to tackle the rising cost of energy – measures that would undoubtedly contribute to collective safety and well-being – are instead being diverted to military expenditure lining the pockets of the already highly lucrative arms industry. This research looks at the funds injected into militarism by western governments in the wake of the war in Ukraine challenging the logic that is driving this response, as well as highlighting its futility in bringing about peace, not just in ending this particular war but in preventing future wars from occurring.

Although there is now a war on Western Europe's doorstep, the trend towards militarism did not begin as a consequence of the Ukraine war, though it has been exacerbated by it. Global military spending was already at an all-time high with the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) revealing that in 2021 it surpassed US$2.1 trillion. Year on year governments have increased military spending and intensified public policy that relies on securitisation and military means to tackle political and social discontent and unrest.

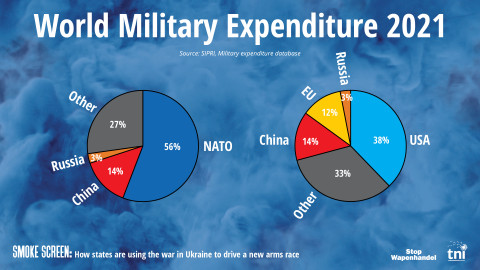

The countries discussed in this research, the vast majority of whom are NATO members, have been steadily increasing their military budgets for years and their collective military strength is vastly superior to that of other major military powers, including rival nations. Even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the combined military expenditure of NATO members was more than 17 times that of Russia and roughly four times that of China - a fact that did not deter Russia from invading Ukraine.

Although militarism fuels rather than dissipates geopolitical tensions with rival powers, since February 2022 governments have continued along this trajectory, ratcheting up military budgets and deploying war-frenzy rhetoric. Instead of pausing, reassessing militarised strategies and concluding that they have not achieved greater political stability, quite the opposite, western governments have doubled down on an approach where there is virtually no space left for diplomacy that isn't overshadowed by the threat of militarism, and scant political will to engage in truly carving out pathways to achieving an enduring peace. How one chooses to spend their money is a good indication of where their priorities lie, and as this research shows, western governments have overwhelmingly prioritised militarism over diplomacy for many years and are continuing to do so despite mounting evidence that this strategy does nothing to curb geopolitical tension.

With regard to the war in Ukraine, conflict analysts have concurred that whilst fully acknowledging the massive upheaval and significant loss of life that has occurred there since February 2022, on purely militaristic terms, Russia’s forces are performing poorly and that the west vastly overestimated its strategic capacity. This underscores the point that Russia does not pose a serious military threat to western nations, the vast majority of whom are NATO members with a far superior military capacity. Yet western governments have nevertheless continued to adopt military strategies, demonstrating a stubborn tunnel vision and a failure to step outside the current paradigm and explore alternative solutions, including promoting military neutrality, diplomacy, de-escalation, and demilitarisation.

Moreover, this war has revived the terrifying prospect of nuclear war, with Russia putting its nuclear deterrent forces on high alert from early on in 2022. The US and Russia possess the vast majority of the world’s nuclear warheads. Although western leaders may argue that ramping up military spending will serve to deter Russia from deploying ‘tactical’ nuclear (or chemical) weapons, the west’s military superiority has arguably had no impact on its military conduct in Ukraine, in particular by recklessly occupying Europe’s largest nuclear power plant at Zaporizhzhia for many months making it a military target. Arming states with sophisticated military weapons systems, even to enable them to defend themselves against a crime of aggression, has no impact on curbing the nuclear threat. The threat posed by nuclear weapons will be countered only through global nuclear disarmament.

By autumn 2022, independent atomic energy experts were in situ at Zaporizhzhia and at the time of writing the immediate threat of a nuclear accident at the plant had somewhat dissipated. However, Ukraine has 15 nuclear reactors, which means that the threat of a catastrophic nuclear incident, either from a deliberate attack or an unintended accident, remains extremely high. This threat will only be countered through diplomacy, as evidenced in the deployment of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), which required agreement from the warring parties, and not through militarism. Indeed, the war in Ukraine serves as a reminder that unless diplomatic relations are nurtured and prioritised, energy infrastructure, in particular nuclear power, which is inherently dangerous, may be weaponised in times of war, placing the greater population, as well as the environment, at high risk.

Another question related to the Ukraine war, which poses a direct and very real threat to vast swathes of Europe's broader population, and which will not be overcome militarily, is with regard to energy supply across Europe heading into winter. EU member states have been tardy in agreeing upon a uniform strategy to offset the energy crisis and have, with few exceptions, passed the price for energy instability on to the consumer rather than addressing massive corporate profit. Public money that could be used to tackle energy price hikes will instead be invested in militarism. At every turn, be it with military spending or the energy crisis, the interests of profit-driven corporations take primacy over the most basic needs of the people.

The drivers of militarised policies, and the real winners once they are rolled out, are the arms companies. In May 2022, Alessandro Profumo and Jan Pie, President and Secretary General respectively, of Aerospace and Defence Industries Association of Europe, said in an interview on Euractiv: 'We are at a historical moment where we – as Europeans – must stand up for our security and our values and principles. We need armed forces that are capable of defending our homes, our territory, and we need an industry that is capable of providing these forces with the equipment they need’.

The message is clear – Europe needs a strong arms industry to guarantee its security at the expense of other areas that critically need financial support. At a time when across Europe the cost of living is increasing exorbitantly and people are struggling to make ends meet, governments are investing shameful amounts of public money in militarism. French President Emmanuel Macron argued that ‘Europe must agree to pay the price for peace, democracy and freedom’, a message echoed by other European leaders. Investing in arms however is futile, counter-productive, and detrimental to building peace and strengthening democracy.

For years, peace activists and the peace movement have warned of the dangers of the military industrial complex and sounded the alarm on how fuelling militarism fuels war. The outbreak of war in Europe has seen the emergence of a deeply troubling public narrative where those who are relentless in their demand for a ceasefire and peace negotiations are framed as part of the problem. They have been ridiculed as idealists devoid of realistic solutions at best, or demonised as pro-Russian war advocates at worst. The fact remains that today's world is significantly over-armed and that the military expenditure of today, outlined in this briefing, and justified as a necessary and proportionate response to the war in Ukraine, will prolong this war and fuel the wars of tomorrow.

Related

At what cost? Funding the EU’s security, defence, and border policies, 2021–2027

- Chris Jones

- Jane Kilpatrick

- Yasha Maccanico

This research reveals the following key points:

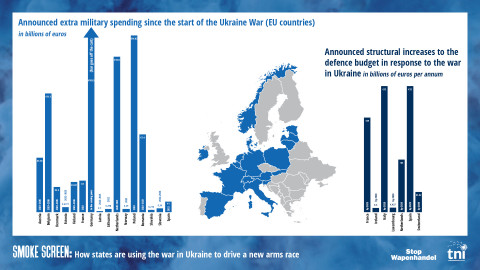

- According to the European Commission, by mid-May 2022, EU member states had announced a total of close to €200 billion in increased military spending for the coming years. This is higher than the entire spending in 2020. Eighteen out of 27 countries in the EU announced increased defence expenditure in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

- In absolute terms, Germany’s pledged military spending is, to date, by far the highest. In February 2022, four days into the Ukraine war, the new German Chancellor Olaf Scholz announced that Germany would both send arms to Ukraine and invest an extra €100 billion in defence over the coming years.

- According to SIPRI, even before the 2022 invasion, military expenditure in NATO countries was 17 times more than in Russia (55.7% of world military spending compared to 3.2%) and NATO is already far superior to Russia in terms of equipment, infrastructure, and overall military strength. The US, by far the most significant NATO member, is responsible for 38% of global military spending; the 27 EU countries combined spend almost four times as much as Russia. The UK alone spends slightly more than Russia.

- In 2014 three of the 30 NATO member states were above the target of spending 2% of their GDP on the military. By the end of 2022 this number is expected to rise to 9, with another 9 countries expected to hit the target by 2025, bringing the total to 18. However, the 2% target has long been criticised as neither being an arbitrary and subjective criterion for judging the adequacy of defence spending. Thus it is more about being seen to do something rather than doing something effectively: it is about symbolism rather than substance, yet while trying to hit this arbitrary target, funds that are vitally needed in other sectors such as health or education are diverted to militarism.

- The European Commission suggested an increase of the European Defence Fund (EDF) budget (now at €8 billion), to be decided in the mid-term review for the current Multiannual Financial Framework (2021–2027), and proposed €500 million (2022–2024) for a short-term instrument to incentivise joint arms procurement. This short-term instrument will be followed by a framework for the longer term: a European Defence Investment Programme (EDIP).

- The largest beneficiaries of the increased spending are arms companies, which profit in several ways: through direct procurement of arms for Ukraine, as well as from other countries wishing to replenish their arsenals after existing stocks are exported or deployed, and through dedicated programmes to support research and development (R&D) activities that invest public money to subsidise private, profit-driven companies. A number of countries set up dedicated state funded programmes to facilitate arms exports to Ukraine, however if such structural changes within state departments become permanent fixtures, they may allow for a fast-track process of more easily exporting arms to other war zones once weapons are no longer being shipped to Ukraine.

- The war in Ukraine has helped the arms industry boost its image and position itself as necessary to keep the public safe. They use this image in their lobbying efforts, for example to be included in the list of socially responsible sectors in the EU taxonomy for investors, which means more access to private funding.

- The war has revived the threat of nuclear annihilation and arms companies producing or maintaining nuclear weapons are pushing for lower restrictions on investment in them, while the energy crisis prompted by the war has put the option of nuclear energy back on the agenda.

- The war has been used to legitimise the position of the arms industry in several other debates, including regarding the easing of restrictions on arms exports for jointly produced arms and military technologies, in particular where this involves EDF funding, and VAT exemptions for transfers of arms in certain circumstances.

Related

Fanning the Flames How the European Union is fuelling a new arms race

- Border Wars

- EU Militarism and War Policies

- Mark Akkerman

- Pere Brunet

- Andrew Feinstein

- Tony Fortin

- Angela Hegarty

- Niamh Ní Bhriain

- Joaquín Rodriguez Alvarez

- Laëtitia Sédou

- Alix Smidman

- Josephine Solanki

Credits

Editors

In collaboration with

Downloads

Publication: Newsletter banner

Did you enjoy reading this content?

Sign up for the newsletter to receive monthly updates on TNI’s research, events, and publications.

Newsletter Subscribe to our newsletter

More like this

-

At what cost? Funding the EU’s security, defence, and border policies, 2021–2027

EU Militarism and War PoliciesReport byPublication date:- Chris Jones

- Jane Kilpatrick

- Yasha Maccanico

-

Fanning the Flames How the European Union is fuelling a new arms race

- Border Wars

- EU Militarism and War Policies

Report byPublication date:- Mark Akkerman

- Pere Brunet

- Andrew Feinstein

- Tony Fortin

- Angela Hegarty

- Niamh Ní Bhriain

- Joaquín Rodriguez Alvarez

- Laëtitia Sédou

- Alix Smidman

- Josephine Solanki