What Way Out Is Awaiting The Mon People In The Future?

Regions

Amidst suffering and conflict, the Mon people are at a precarious crossroads in Myanmar. Following the 2021 coup by the military SAC, the New Mon State Party tried to stay neutral by its 1995 ceasefire. But Mon communities have continued to suffer the same repression, hardship and sometime violence as other nationalities across the country where resistance to military rule has deepened and spread. Last year, this led to a split in the NMSP movement with a pro-federal grouping returning to armed struggle. In this commentary, Kun Wood describes the plight of the Mon people, highlighting the difficult challenges they face. As she argues, unity is the key answer and the greatest defence in protection of the Mon people and cause.

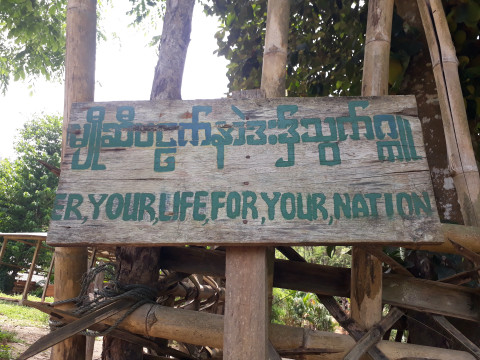

Photo credit TZ

The Mon population are struggling in daily lives for their next meal

The end of this winter will mark the fourth year of the attempted coup by the military State Administration Council. The ongoing brutality, violence and oppression of the SAC are still rampant in different shapes and form every day across the country whilst the winter, summer and rainy seasons have taken their turn. Mon society is also among the populations that are suffering. We have grieved and mourned for over three years already, but the suffering shows no sign of cessation yet. The majority of the people are barely surviving under endless difficulties and hardships. The future is precarious, and hope is nowhere to be found. For ordinary people, the challenges are still ambiguous: “where are we heading and where are we right now?”

We wake up every day with the same questions: when will we get our liberation, when will we get our freedom, why is liberation is still a faraway dream, and why are we trapped with wars and grievance while other countries seem to be moving towards a better future? Who will answer these questions for us? Why is it like a vicious circle? Our days always start and end with these uncertainties. People are facing multiple pressures and crises, although some changes in the dynamics occur from time to time. In general, the crises vary depending on the different locality.

Mon people are proud to claim themselves Mon. For the first time since the collapse of the Hanthawaddy dynasty of the Mon kingdom, a new dream of a better future recently emerged after centuries of repression and neglect along with the current popular struggle for change. The new dream of the Mon people is to build a future federal democratic union together with other ethnic nationality peoples living across Myanmar. The political forces leading the Mon cause, including the New Mon State Party, have again mobilised with the goal of greater self-determination, national equality and an end to all forms of dictatorship.

In these tasks, the NMSP has historically demonstrated its ability to mobilize sympathetic forces and build alliances, always being involved in political actions and movement. For these reasons, the NMSP has been regarded as a dependable organisation by the Mon people when we talk about the Mon national cause. The question, then, is why the underlying problems have never been solved even though the political dynamics change from time to time?

In answering these questions, it is important to generate lessons learned from mistakes made in the past instead of simply blaming the past for errors. In this respect, our recurring political crises could be explained as a “political trap’’ or a “conflict trap” that has become protracted throughout history. In essence, the political crisis has remained in the same conflict trap though generations have passed. Initiatives have been tried but similar obstructions and disappointments always occur.

The evidence is worrying. In 1995, the NMSP signed a ceasefire agreement with the military government. But this change brought benefit for just a few while the majority of Mon people were left out. Subsequently, the Myanmar military, known as the Sit-Tat (Tatmadaw), also tried to force the NMSP to transform into a Border Guard Force. Then again the NMSP entered into political dialogue with the quasi-civilian government of President Thein, through the joint representation of the United Nationalities Federal Council, after a new peace process was started in 2011. This, however, was also disrupted. But in 2018, after facing various kinds of pressures, the NMSP became a signatory to the 2015 Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement as a means to try and silence the gunfire which was still afflicting Mon society. But, with the SAC coup in 2021, all these processes and efforts at political dialogue and reform are once again at an end.

The conclusions to be drawn from this appear very clear. Although many attempts have been made, the country is still trapped in a vicious circle of conflict up until today. At the root of this, the lack of political will by the Myanmar military to resolve problems that should be solved by political dialogue is the main reason why the challenges remain unsolved. With decades of experience, the Myanmar military has become very good at playing “divide and rule” tactics between the peoples, both neglecting the causes of conflict and turning allies into enemies – or vice versa – to fulfil their agendas. In the light of the 2021 coup attempt, opinion is widespread across the country that the SAC has behaved like a terrorist organisation, that it is the underlying cause of all the crises, and that the peoples will only be liberated after the SAC is brought down once and for all.

Mon society still far away from the dream of federalism

For these reasons, the NMSP should carefully reassess whether the path that they have been taking is moving forwards or backwards to achieve the Mon people’s dream of a federal democratic union. The Mon revolution started in 1948, more than 75 years ago, and has also witnessed a ceasefire period of over 30 years that started from 1995. In establishing this truce, the NMSP made an agreement with the military regime to negotiate about political affairs at the table to resolve political problems, without further bloodshed, through the agreement of reforms that will guarantee self-determination, national equality and federal union-building.

Regrettably, history showed the ceasefire to be a showcase of rhetoric during which the Myanmar military sought to strengthen its position, and the dream of Mon people has yet to be achieved. Across the decades, successive dictators have shown no will to resolve the political crises. And now, the whole country has witnessed the brutal atrocities and human rights violations by the Myanmar military since the attempt to seize power in the 2021 coup.

The current situation on the ground therefore raises many questions for the position of the NMSP. Why does the party keep talking with a military dictator destroying their political goals? What do they expect to achieve? Or have they given up their goal of revolution? Will the Mon people be oppressed forever? The NMSP has to take account of many issues. Many lives and many territories have been lost along the way during the past 30 years of ceasefire, and the people who own the land have become guests on their own lands. How does the NMSP feel about that? Are they ready to give up the dream of federal democratic union? Are they going to just forget and ignore the lessons learnt during the previous 30 years? Which political direction are they heading in? Are they going to submit themselves as puppets to the military leader Min Aung Hlaing? What will happen for the future of Mon generations to come?

In considering these questions, it is right to say that the NMSP has been considered a legitimate representative of the Mon people whom the whole Mon population is counting on. This commentary has no intention to blame. Rather, it seeks to be an encouragement to learn from the past and walk together with other ethnic nationalities in building a federal democratic union in the future. In doing this, the NMSP – along with every Mon – have the responsibilities to share in achieving the goals of the long Mon struggle.

Photo credit Kun Wood

Differences of opinion and the importance of unity

On 14 February 2024, a faction split from the NMSP called the New Mon State Party Anti-Dictatorship (NMSP-AD), choosing a different path. Disputes over joining hands – whether with the SAC or not – was the main trigger among NMSP members leading to the separation. The NMSP-AD has established five political goals:

(a) to fight against all forms of authoritative regimes including military dictatorship

(b) to abolish the 2008 constitution

(c) to establish a federal democratic union which fully recognises the right to self-determination of ethnic nationalities

(d) to build solidarity among the Mon people and social cohesion with all ethnic nationalities

(e) to establish a Mon State that fully respects the equal rights and self-determination of all ethnic nationalities including the Mon people.1

At the same time, other new resistance forces have emerged among the younger generation with the goal of defeating the military dictatorship. In theory, there is no problem in having so many groups when there is a common political goal. Nevertheless it will be wiser to ensure that there is a synchronized unity of efforts in place rather than taking diverse and dispersed positions.

As these events warn, complacency and seeking to sit on the fence in the midst of conflict will no longer be enough. The resilience of the local population has nearly reached its limits while the resistance tide is gaining stronger momentum across the country. Some revolutionary forces have already seized townships in several areas, and this kind of political juncture is unprecedented in the long years of struggle since the country’s independence in 1948. For this reason, the justification made by NMSP leaders that “we are concerned about the impact on people” is no longer considered sufficient explanation for their inaction and apparent submission to the SAC. Mon communities are also suffering from the nationwide warfare – as are all nationality peoples in the country. Eventually, it could become too difficult to move in any direction if Mon leaders seek to stay in their “comfort zone” too long.

For this reason, the NMSP should no longer be daydreaming about a sham union of Myanmar under the control of the SAC when it is clearly the best time to build a genuine union together with other ethnic nationalities in alliance as they all truly want. They will never be able to get out of the conflict trap if they continue working together with the SAC. The whole Mon population are likely to be enslaved forever by the military regime unless the NMSP decides to break free themselves. The regime’s proposal for another general election is illegitimate, and the peace process has also proven fake. Military regimes in Myanmar have no history of keeping their promises, and they are the most deceitful organisation that the people have witnessed along the way. The SAC have a complete lack of will for political reform, and regime officials only focus on their own interests above others.

The NMSP leadership now have many issues to consider. The movement suffered great losses in human resources and military strength after the 1995 ceasefire agreement. There were many reasons behind this cause. As Mons, the people do believe that NMSP decisions are well intended to keep the lives and wellbeing of civilians safe. On the other hand, NMSP leaders know very well that negotiations with the Myanmar military over 30 years have brought no successful result. There can be no doubt that the NMSP is an organisation with impressive experiences in revolutionary history, overcoming many battles in the past while joining with alliance forces. But, to date, it is also recognised that the different alliance movements have also fallen short in achieving their intended outcomes and political results.

In summary, the NMSP is more like a priceless ruby for the Mon people. But the real value of that ruby has slipped away in the mud by cooperating with the regime. It is therefore vital to consider, revise and make our own decisions if we are to revive our own values.

In the meantime, independent travel is very difficult within Mon State and the surrounding region, but concerned people have many questions. The following are responses to subjects that frequently attract attention.

Public concerns over the rapid increase in so-called “development projects” across the Mon region while armed conflicts are rampant after the 2021 coup

Investment projects in the name of development have increased rapidly across Mon State after the SAC’s attempt at the seizure of power. According to U Thin Tun Aung, director of Investment and Company Administration: “There were 93 investments between 2021 to 2024 in Mon State. 37 out of 93 were foreign investments and the remaining 57 were businesses owned by Myanmar nationals.”2

Mon State is a coastal region with open sea entrances. It is therefore time to raise serious questions. What benefits have these investments in Mon State brought for the NMSP and Mon communities? Who owns these projects? Which stakeholder plays what role? Who receives what benefit and how are those revenues being shared? But, for the moment, demands for federalism and peace to resolve these issues are being concealed by the SAC while it is the civilian populations who face the suffering.

There are also special questions relating to such larger business projects as rubber factories, the deep-sea port and airport. At the same time, natural resource extraction is finite and irreversible. But if so-called development projects under the SAC are indeed beneficial to the Mon people, does that mean that they no longer need to go outside the country to seek work? Does the SAC’s peace process only mean for their own business interests? What percentage of these investments belong to the Mon people? Satisfactory answers are essential for it is the local Mon communities who must bear the potentially negative consequences in the end.

In another development, local communities are also witnessing the sudden rise in Chinese people across Mon State lately. Many of them do not speak Burmese, although they apparently hold Myanmar identity cards. It is unclear why they migrate to Mon State, where they come from and for what reasons. At the same time, the outgoing number of Mon people departing to other countries for work has increased while Chinese arrivals are moving in. It feels like the hosts are leaving their beloved homeland for guests and newcomers to take over. What benefits do the Chinese expect to generate in Mon State? How would Chinese businesses contribute to the struggle and future of the Mon people? A similar trend is also being noted in adjoining Karen State where many Mon people live.3

Against this uncertain backdrop, Mon communities are continuing to suffer immense pressures and difficulties with no end in sight. Illegal taxation, displacement, and insecurity of homes and livelihoods have increased across the region, with those living in rural areas especially vulnerable. Naing Htaw Aung, for example, runs a private transportation service from Mawlamyine to Ye town, and he shared his daily struggles as a driver:

“It is very difficult for me, although I am transporting passengers, as there is no security and we have nowhere to file our complaints. The number of passengers travelling have greatly reduced amidst rising prices of fuel. There are also more than ten checkpoints with bamboo poles along the journey from Ye to Mawlamyine demanding informal taxes. You have no right to bargain with the fees they have imposed at some checkpoints, and some checkpoints even demand to hand over certain commodities as a custom fee. Only a few checkpoints are flexible to negotiate with, and it makes our lives very difficult. Lives are so cheap in Myanmar and I would want all armed conflicts to end immediately if it is possible.”

Conscription law and young Mons: why are large numbers of young Mons leaving the country?

It has traditionally been quite common for Mon people to go abroad for better job opportunities. But the number of Mon leaving the country nowadays is at unprecedented levels, through both legal and illegal means, unlike before the 2021 coup. Only a few of them are going out for further study and the majority are destined for hard labour and precarious jobs. But, as the SAC now steps up forced conscription as the Sit-Tat declines in strength, the numbers of young people of military age who are seeking to depart has accelerated rapidly, and it is uncertain when they can ever return.4

Why are the problems presently so difficult to resolve?

For the moment, a major struggle is underway across the country with the people determined to achieve political change while the SAC wants to return to a regressive past under military domination. In the process, control of many townships in northern Shan State has been taken under the administration of anti-SAC resistance forces following "operation 1027" and the capture of several towns. Meanwhile a similar advance by anti-SAC movements has been witnessed in other parts of the country, such as Karenni (Kayah) State where “operation 1111” was launched.

To strengthen civilian administration, new governance institutions have been established in ethnic nationality territories, such as the Karenni State Interim Executive Council and Chinland Council. Similar initiatives are also continuing in Bamar-majority areas, including Magway and Sagaing Regions. In response, the SAC is responding with ever greater violence against civilian populations, including aerial and artillery attacks, causing major loss of life and displacement. Despite this, nationalities across the country are continuing to build momentum towards their goal of a future federal democratic union.

How the suffering of other states has affected the Mon population

To answer this question in short, we are also facing the same magnitude of difficulties which are coming against the people from every direction like others. Civilians are being shot dead. The number of landmine victims has increased. Indiscriminate aerial bombardments have burnt down the homes of many civilians. The houses and properties of those displaced are being looted. Against this backdrop, travelling is no longer safe or secure, and burdensome fees are being imposed on movement and traffic.

What has the Mon political party, the Mon Unity Party, been doing and where is it standing now?

The electoral Mon Unity Party made a public statement last year that they have been working together with the SAC to keep the Mon national cause safe and alive. But the time is passing and it is now four years since the coup. So the public are asking many questions. What has the Mon Unity Party achieved during these years? What contribution have they made to address the social, economic and political causes behind conflict in support of the Mon people and the public interest so far?

Like other displaced peoples, Mon civilians are also running for their lives and have left behind their properties. So the question for the MUP is: how does the Mon situation look different in your eyes since you decided to work together with the SAC? Mon civilians are facing enormous difficulties and multiple crises. On the one hand, they are trying to overcome such challenges as the rise in commodity prices due to inflation, while on the other they face the day-to-day occurrence of grave human rights violations. Many are living in impossible conditions for long-term survival.

Following the NMSP-AD split, what political direction do the Mon people want to see from the NMSP ‘mother party’?

We, the Mon people, must step up the struggle for greater self-determination alongside other nationalities resisting the SAC for different reasons. Everyone must make their own efforts for liberation. The era of military rule will only be prolonged if Mon parties are still thinking to take a free ride without any political motivation. Unity is the strength of the Mon people. In unity we can see the true strength of the Mon people no matter what our differences are. And the unity of the Mon people is the biggest nightmare for our opponents. We therefore need to have common goals, although we may take different paths to reach our destination.

The rights of other ethnic nationalities living in Mon State are also our strength since we must build a future federal union together. To achieve this, we need to have a better strategy for the future ahead of us. Enemies and opponents may set you traps in their game unless you come up with comprehensive and meaningful strategies to counter this.

The present times are dark. But, after many decades of experience, the NMSP has – until now – been the most reliable political entity for the Mon people. We thus need to be mindful that one wrong political move at this time may lead to failure in eternity. The population in Mon State has been scattered to the extent that there seems no land left to sow our seeds. Where shall the Mon people then go? Are we going to end up as migrant workers in other countries forever? These are the questions that we now urgently need to answer.