Power switch Building a just energy transition in an age of corporate and imperial power

Energy based on fossil fuels is at the heart of a capitalist system that has concentrated power and wealth and threatens life on Earth. For our opening essay, TNI brought together an expert on Big Oil in the Middle East, an academic and activist working for a just energy transition, and a leading labour organiser in the oil industry in Trinidad and Tobago to discuss the dynamics of power in our current energy system and how to transition to a democratic, just and sustainable energy future.

Illustration by Matt Rota©

Nick: We have examined power relations in the global economy now for 12 years through this report, State of Power. It was interesting to me in this edition on energy that the word power had a very much a double meaning, who has power over our systems, but also the power that energy gives us and the global economy. And so the first question I wanted to pose initially to Tim was how do you feel our fossil-fuel-based energy system since the nineteenth century has shaped the way power is distributed today. And, in turn, how has power shaped our energy system?

Tim: In my book, Carbon Democracy, I made an argument that I can summarise in one sentence, that coal made possible mass democracy and oil set its limits. The argument is that in the nineteenth century when industrialised states became highly dependent on coal as a single source of energy, workers had an unprecedented political power because for the first time, they could shut down a country's energy system, in what came to be known as the general strike, where coal workers, rail workers, and dock workers could interrupt that supply of energy.

This power was critical to the emergence of mass democracy in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Oil undid this, partly because it provided an alternative, so it was easier to weaken that force of organised labour, but also because oil was different, being liquid that came out of the ground under its own pressure. So, you didn't have to send workers underground and you could route it very easily through pipelines and oil tankers in more flexible ways that were more difficult to disrupt.

Even so, oil workers in the Middle East were just as determined as coal workers in Europe to win political and economic rights. In Iran, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia, the three main Middle Eastern oil states, workers organised strikes, such as the general strike in Iran that led to the 1951 nationalisation of oil. But the kind of power that workers had acquired over the energy and political system in earlier decades was lost, especially because oil production was developed in other parts of the world than the centres of capitalist industrial life. That meant a distance opened up between those who were involved in the consumption and those involved in the production of energy, making it difficult for oil workers in a place like Iran to forge links with political struggles in the West.

So, I think oil had a profound effect on the emergence of political forms in the twentieth century through its capacity to undermine democratic politics everywhere.

The structure of our fossil capitalism is tightly interconnected with the structure of global power, economically and geopolitically. It's also true that the tightly connected systems of global power and fossil capitalism have also created important challenges to that system that have exposed its vulnerabilities, chokepoints or weaknesses... So energy is not just a site of hegemony, but also a site of contestation.

Nick: Thank you, Tim. Perhaps I could bring in Ozzi because you, of course, have both worked and organised in the oil and gas sector. So how do you see this interplay of energy in the distribution of power through your own experiences?

Ozzi: Well in the case of Trinidad and Tobago, it was a little different from say the UK. Trinidad and Tobago did not have a coal industry and was mainly agricultural until the emergence of oil, which then began to drive the energy system. The emergence of an oil-based fossil-fuel industry was coupled with the emergence of one of the most powerful unions in our country, which is the Oilfields Workers Trade Union. So, it did build worker power. And that the union was instrumental in bringing about universal adult suffrage and independence.

It was oil workers coming out of the labour riots in the 1930s that gave rise to a sense of nationalism and laid the foundations for what would be an independent Trinidad and Tobago, which we declared in 1962. This showed that the broader energy system can give rise to mass democracy.

When I reflect or think about the energy systems, I immediately think of imperialism and the fact that the architecture of the energy system is very similar to colonialism and empire, where you have a small concentration of people or organisations that control it.

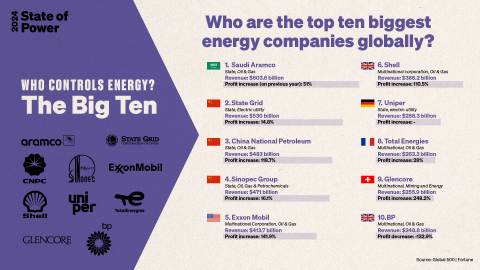

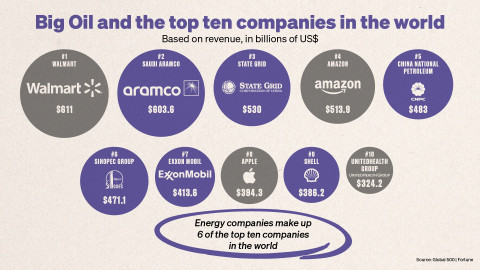

One of the first modern multinational corporations was an oil company, Standard Oil, in the late 1800s. After World War l, it was oil consortia that made agreements with the British and French empires as they carved up the former Ottoman Empire. And even today of the ten oil giants, seven of them are US and Anglo-European. Of the other three, there are two Chinese and one Saudi firm. So, you can’t talk about the energy system without talking about power. And that relates to global capitalism, which is driven by commodity production, energy production and consumption.

Thea: Once you think about it, it's quite obvious that the structure of our fossil capitalism is tightly interconnected with the structure of global power, economically and geopolitically. It’s also true that the tightly connected systems of global power and fossil capitalism have also created important challenges to that system that have exposed its vulnerabilities, chokepoints or weaknesses.

We can see that the late 1960s and early 1970s when what was then called the ‘Third World’ started to organise. For example, the Organization of Petrol Exporting countries, OPEC, emerged at a time when Third World resource producers were seeking to take control over these resources and for which they didn’t receive the benefits. OPEC was one inspiration or even model for a broader proposal for a New International Economic Order (NIEO), which was never fulfilled but still resonates as an idea today.

So, energy is not just a site of hegemony, but also a site of contestation. I've researched Ecuador, Chile and other Latin American countries and around the region where there continues to be a powerful idea of resource nationalism, which emanates from workers’ unions as well as social movements and popular coalitions. The idea is that ‘we, the people’ should own the resources and the global North should not keep extracting from us. It is a form of contestation that is also present in our energy transition moment.

Nick: Big Oil’s rise particularly in the last few decades has paralleled a massive financialisation of the economy. How are they interrelated? And what’s the situation now in terms of the power of Big Oil, both state-owned and private firms?

Tim: In terms of oil and finance, the two grew up together. The large multinational oil companies were also the largest publicly owned shareholder firms and associated with some of the largest banks. One reason for this intersection is first, energy production is enormously expensive and so requires vast amounts of capital. The second is its capacity to generate extraordinary profits that attracts finance.

This is not just because of the world’s dependence on energy, but because structures of energy production are relatively durable, so once built they are going to produce revenue for decades, which is not often the case with other industrial processes. And it's the ability to capitalise that future revenue that explains the extraordinary capitalised value of large oil companies. Ensuring that money flow is why you get an entire politics of energy security.

Ozzi: In terms of the interplay of energy and finance, if we go back to the 1970s’ energy crisis, it was really a financial crisis. Indeed, that crisis played a critical role in the renewal of the United States power over global finance, because it resulted in the convertibility of US dollars to gold, and it led to the reproduction of the petrodollar, which enabled the flow of money from USs multinational banks to non-oil producers and less developed countries. It led to this shift from institutional borrowing to commercial borrowing that repositioned US private banks which would then go on to dominate the global finance sector in the same way US oil companies dominate the global energy sector.

This led to the serious debt crisis among many countries in the global South and enabled neoliberal advocates and imperial power to impose structural adjustment programmes which consolidated imperial and neo-colonial power relations and entrenched these vast unequal relations of power.

Thea: It's a very contradictory moment to ask this question, because we're in this early but still uncertain and very uneven energy transition. On the one hand, the International Energy Agency (IEA) forecasts that demand – not supply – for fossil fuels is going to peak in a few years. There are also forecasts of upwards of $1 trillion in stranded assets if the energy transition happens – which would be an enormous hit to energy firms and the financial system.

This might suggest the fossil-fuel industry is in its death throes. But that’s obviously not the case because they have also had record profits, due to geopolitical instability and still growing energy demand and a lot of that demand is still fulfilled by fossil fuels.

There are also new dynamics, such as the rise of private equity investors in fossil-fuel production, outfits that are more opaque, more difficult to govern even than a multinational shareholder-owned firm.

As Brett Christopher has shown, these equity firms are moving into energy and infrastructure, which means they increasingly own central social infrastructure. They are often turning over these assets in a vulture fund kind of way, seeking to eke out value and then sell it off. Ironically, they have moved to acquire more dirty energy infrastructure in part because of the divestment of some pension funds and other institutional investments from fossil fuels, which might make it harder to phase out the sector. So, it's a perverse outcome of an otherwise admirable move on the part of some institutions and investors.

Nick: And how are the shifts in energy systems intersecting with the geopolitical shifts with the rise of economic powers such as China and India?

Tim: Well one of the elements of change is certainly the rise of China and India, both as consumers of energy and particularly in the case of China, as enormous producers of energy. But the US too, which had been the world's largest producer for many decades and after the 1970s had gone into decline, with the rise of so-called tight oil, or oil produced by fracking, has had an entire second life as an energy producer. This has been disruptive because it is not controlled by the large oil multinationals who control the price but is increasingly in the hands of new or smaller oil companies, with nobody controlling the price.

The result of that has been this extraordinary volatility of oil prices, and the rise of private equity firms is partly because they are able to use that volatility to make money.

Nick: And Ozzi, what about non-US players, such as Venezuela or China? Perhaps you could share a little about the conflict between Venezuela and Guyana that is taking place in your region? What do they reveal about the energy system and geopolitical jostling that's going on right now?

Ozzi: The first thing to note is that US Big Oil, ExxonMobil in this case, remains centre stage. But first to explain the land dispute, which goes back over 100 years to the colonial era when Guyana was British Guyana and Britain was trying to expand its imperialist influence and Venezuela was an independent nation. This dispute was more or less laid to rest when Chávez visited Guyana in 2004 and announced that he considered the issue finished.

Things began to change in 2006, when the Chávez government began a series of nationalisations and regulation of the oil sector. Most multinational oil companies had accepted the new terms, except for two, ConocoPhillips and, of course, ExxonMobil. They had demanded tens of billions of US dollars in compensation through the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID).

However, in 2014, the ICSID ruled that Venezuela pay ExxonMobil only $1.6 billion, which infuriated the then Chairman and CEO Rex Tillerson. A year later Exxon announced that they had found, all of a sudden, 295 feet of high-quality oil, and when you look at the production-sharing agreement between Guyana and ExxonMobil, they were given 75% of the oil revenue towards cost recovery and the rest shared 50:50 with Guyana. They also had an Article 32, Stability of Agreement that says that the government shall ‘not amend, modify, rescind, terminate, declare invalid or unenforceable, require renegotiation of compel replacement or substitution, or otherwise seek to avoid, alter or limit’ this agreement.

In other words, neither the people of Venezuela nor the people of Guyana will benefit from ExxonMobil's political intervention in our region. So, this is not a conflict between the two populations, but rather a conflict between ExxonMobil and the people of these two South American countries. In fact, just after Guyana signed the Argyle Declaration for dialogue and peace with Venezuela on 14 December 2023, declaring that neither party will use force, a British warship visited Guyana on 29 December 2023.

It should also be noted that in July 2023 President Xi Jinping met with the Guyanese President, Mohammed Irfan Ali. At that meeting Xi Jinping emphasised the relationship between China and Guyana and the important role of China in Guyana. Mr Ali reaffirmed that point and stated his admiration for China’s leadership and global influence. It is clear that Guyana is fast becoming a battleground for global geopolitical positioning. This is another clear example of the inextricable link between the global energy system and imperial competition.

Nick: Tim, in your book, Carbon Democracy, you also looked at how oil politics had shaped militarism, particularly in the Middle East, and in relation to Israel and the 1967 war. Does the war directly or indirectly have its roots with the carbon authoritarianism or carbon militarism that you talk about in the book?

Tim: Yes and no. And indirectly rather than directly. The war on Gaza has its causes in an Israeli state that wants to completely dominate the area of historic Palestine and not tolerate any kind of Palestinian demand for national rights. Where those larger connections to the geopolitics of oil come in is that Israel couldn't get away with this without US financial, military and political support.

The influence and the propaganda system that Israel is able to organise to maintain the support of the US government is related to US militarism, which is very much tied to the history of oil. The US spends more on its armed forces than the next ten largest military powers in the world.

This is sometimes explained too simplistically in terms of the US need to defend vital resources such as oil. A better view is that the misleading idea that oil supplies are somehow vulnerable –rather than a cause of our vulnerability to climate collapse – is used to generate the sense that somehow US security in general is at risk. This language of vulnerability is essential to the diversion of such vast public resources into the hands of the weapons and security industries.

So, it's not directly to defend oil that the US has got to be on Israel's side, but because, like Israel, and with Israel’s help, it is defending the myths of insecurity on which its own militarism depends.

Nick: I want to take the conversation from the military to the ecological sides of this question. Our energy system is clearly destructive to our planet with its impacts on climate, the environment and health, so why has it proved so difficult to change course?

Thea: This gets into deeper questions of politics and power and also the mechanics of the capitalist system. I mentioned the phenomenon of stranded assets. This is an issue as fossil fuels like any extractive sector have a lot of high upfront, fixed and even sunk capital costs. And so you're making the bet that over time, sometimes decades, you are going to get a return on that investment and before that it's just a cost. It’s not hard to imagine why owners of fossil-fuel assets are incredibly resistant to transitioning the energy system, even if there are opportunities for them to profit in the new energy system.

And given how politically influential and connected the industry is, it are very well positioned to coordinate and delay and deny and do all of the things that we know that they have done. The other issue is that the industry is deeply implicated in the materiality of capitalist life, if we consider petrochemicals or the plastics industry. It’s why some people then say it's hard to imagine the end of oil without imagining the end of capitalism.

But there are also reasons that it's hard to change our energy system beyond the interests of the most powerful, for example for low- and middle-income oil-exporting countries like Ecuador. I continue to be surprised that there is absolutely no plan and no discussion in centres of institutional power about what's going to happen with countries whose entire fiscal basis is tied to oil revenues and who cannot provide social services, public infrastructure, or the basics of governance without those revenues. We can’t avoid dealing with the difficult reality that transitioning away from oil would deny a crucial revenue stream to a number of poor, low- and middle-income states.

Oil has very much shaped our entire modes of economic thought that in turn shape energy and the transition. There is a relationship between the history of oil in particular and conceptions of growth, in which apparently limitless reservoirs of oil were seen to justify an economy based on growth. We can see that today in the continued expansion in the use of fossil fuels that is predicted to continue to at least 2030.

Nick: And that, of course, very much relates also to Trinidad and Tobago. So, I was wondering Ozzi about your thoughts on the ecological impacts and why it's been so hard to transition from this form of energy?

Ozzi: Thea has raised a concern that is critical for small oil and gas-exporting countries like ours. Our entire economy has been based on oil and gas for many decades and still accounts for almost 40% of our GDP and 80% of exports. In fact, the energy sector contribution accounted for 58.2% of the government total revenue. Without those revenues, we are faced with a National Insurance, which is the entire national social security safety net, under threat of collapse. So, it becomes a real challenge to transition.

We are engaged right now in a struggle for a progressive just transition in Trinidad and Tobago, mobilising our membership to steer the government away from a neoliberal transition. They call it a just transition, but it's not. It's nothing more than a cloak to conceal a new wave of structural adjustment programmes. We've had thousands of job losses and still no new promised jobs. What they are doing is actually commodifying and privatising ever more public utilities like water and electricity.

And they are not even changing energy sources, as they are signing new gas deals. They are also signing agreements with the same multinational firms for any renewable projects – for example, Trinidad and Tobago is working with BP on solar energy projects. So, we have to protect ourselves from green imperialism and green capitalism.

Tim: Oil has very much shaped our entire modes of economic thought that in turn shape energy and the transition. There is a relationship between the history of oil in particular and conceptions of growth, in which apparently limitless reservoirs of oil were seen to justify an economy based on growth. We can see that today in the continued expansion in the use of fossil fuels that is predicted to continue to at least 2030.

And the nature of green imperialism means that transition is uneven too. In most European industrialised countries, possibly even the US, fossil-fuel consumption is lower today than it was in 1990. The continued expansion is mostly happening elsewhere, reflecting the fact that for certain countries finding the capital to invest in offshore wind and utility-scale solar is expensive. There are tipping points, such as the relative cost of renewables becoming cheaper than fossil-fuel sources of energy, but it takes a while for those tipping points to work their way through the system and it's not happening fast enough.

Thea: To add to Tim’s reflections, as well as the high capital costs for renewables, the actual profit of these sectors is low and still uncertain compared to fossil fuels. What that means concretely is that government subsidy is very important – which takes the form of de-risking (underwriting the risk), active tax credits, tax abatements, offsetting of capital costs, cheap loans and so on. Most global South countries cannot do that and are constrained by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), its loans and its creditors in providing public investment. And countries like the US, that can do this, do not do enough to get an energy transition going.

Putting aside whether we think states should be underwriting private profits, it’s a big issue in terms of why the transition has slowed and why China and the US, for different reasons, stand out in their ability to underwrite any kind of transition.

Nick: As well as addressing the exclusion of countries from this transition, how can we also address ways that the transition can exclude workers or have negative impacts on communities, for example with the extraction of transition minerals in the global South?

Thea: As we look upstream at the mineral inputs of the renewable energy technologies, there’s a whole periodic table of elements considered critical or essential, such as cobalt, lithium, rare earths, graphite and so on. And they raise a lot of concerns and dilemmas for global South producers.

First because in comparison to oil, it’s hard to imagine sustaining a country on lithium revenues, because the size of the market does not compare and they're much more dispersed. So, the question of producer leverage, such as we have seen with OPEC, becomes more difficult.

They also come with a lot of ecological and social impacts and also labour exploitation. So, while it doesn't have the same carbon footprint as the fossil-fuel industry, mining has a tremendous amount of local environmental and social harm associated with it and one of the worst records in terms of human rights violations. Agribusiness and the mining sector compete for that nefarious title in terms of where people get killed or where workers get repressed.

So, expanding renewable energy technologies as necessary as they are for solar panels, lithium batteries, etc., is concerning from a human rights, governance and ecosocial perspective. We can see a lot of reproduction of neo-colonial relations in terms of their impacts.

So that's a familiar story. But there's also something else happening at the same time, which is a process of onshoring, where the US government, for example, is saying they don't want to rely on these volatile supply chains and want to have lithium and cobalt extracted in the US. On the one hand, we could say that's globally just because the US should pay the ecological social price for all of its extractive needs, but in reality it’s not replacing extractivism in the global South as the whole demand pie is growing. And the mines in the US are also mostly affecting Indigenous peoples and rural Latino communities, in other words the same vulnerable populations which are most affected in the low and middle-income countries.

It has also fuelled a race to the bottom as global South mineral producers seek to compete with the US for investment, even though the US government is offsetting capital costs and providing tax breaks to mining companies.

History has made it clear that the current energy expansion is inseparable from capitalist expansion. This is what is driving the climate crisis and the breakdown of the world's ecosystem. So, any viable and effective means of curtailing the energy expansion and mitigating the climate impact must involve taking control of how energy is generated and used.

Nick: Ozzi, I know you're involved in movements of workers experiencing the transition and seeking to build a just transition. What’s your experience?

Ozzi: As I mentioned, in Trinidad and Tobago we are experiencing an unjust transition. We are still signing new oil production contracts with BHP Billiton, Shell, BP, while the jobs that are left are jobs that no longer have decent terms and conditions. It's almost as though there is a reversal back to the 1930s and 1940s, when workers had absolutely no rights in the energy sector.

Our union is working with Trade Unions for Energy Democracy to present an alternative, framed along what is called ‘the public pathway approach’. This looks to lay out a path that would extend public ownership of energy and build a new political economy consistent with the hopes and aspirations of many of us working in trade unions and social movements. This would mean the complete nationalisation of both the energy and power sectors.

History has made it clear that the current energy expansion is inseparable from capitalist expansion. This is what is driving the climate crisis and the breakdown of the world's ecosystem.

So, any viable and effective means of curtailing the energy expansion and mitigating the climate impact must involve taking control of how energy is generated and used. Control of energy is critical given technical realities and also from the perspective of political strategy. So, the struggle for energy can provide a clear focus for us in movements to strive for radical, systemic change.

Nick: Tim and Thea, as we push for a citizen-led, a worker-led, more democratic just energy system what do we need to grapple with? What do we need to change about the energy system?

Tim: I can’t add to what Ozzi says. He shows us so well that energy is not just a technical question of providing a certain number of gigawatts, but it is where our politics is being organised and where questions of justice and social justice are at stake. And that political awareness has not been there in various moments in the past and therefore its re-emergence is quite promising given the scale of the transition that we've got to go through.

Thea: I want to circle back to something I was saying earlier, which is about the hesitance of capitalist investors to invest in renewable energy, which leads to public subsidies of privately owned infrastructures. This raises the question of why not cut out the intermediary. If the public purse is already subsidising and passing major legislation like the Inflation Reduction Act in the US, in order to get any of this transition going, why don't we think about direct public ownership of generation capacity, ownership of the wires and cables of distribution?

In New York State, for example, I've worked on research that supported the Democratic Socialist of America’s (DSA) campaign that succeeded in passing legislation that empowered a state-owned entity that owns generation capacity to buy more renewable capacity and to help decarbonise public buildings. The question of ownership is critical now because it's very apparent that we can't rely on the profit motive to decarbonise as quickly as the climate science demands.

A second answer lies with labour unions and labour militancy. In the US, a few years ago, we had an important development when the United Mine Workers that represents coal miners finally officially endorsed a just transition. This is critical, because a just transition requires organising workers who want a transition and to organise around it so that they benefit from it, rather than delaying a transition, being fearful of it and allying with their bosses.

Recently we also had this major, important, very militant and creative strike organised by the UAW, United Auto Workers that sought to make sure that workers are in the driver's seat, pun intended, of the Electric Vehicle (EV) transition, because the EV transition can work out in all sorts of ways for workers. There are fears of layoffs, of automation, precarisation. But the UAW decided to be a protagonist, and won tons of amazing contracts that ensure that battery workers and EV workers will have the same kind of standards as traditional auto work.

It’s an example of what can happen when unions organise less on the defence of protecting jobs and dirty industries and more on the offence of shaping the kind of renewable energy transition they want. This is not to say that it's not still a very asymmetric battle with corporations and bosses, but I think it lends itself ultimately to more power for workers.

Nick: Ozzi, I wanted to give you the final word. We have a lot of readers of this publication who are involved in energy struggles, up against very entrenched systems of power. What is your message to them?

Ozzi: Well recently, OWTU with other unions of the global South launched TUED South, to show that there is a plausible and legitimate alternative of a public pathway to the existing and failing privatised decarbonise approach. My message is that we must never stop demanding system change.

The demands for system change are the only just responses to tackling the climate crisis. When we transitioned to capitalism, it had a negative impact on the environment. So, what is required is to transition out of capitalism for the vast majority of countries, and especially in the global South.

Without strong and progressive interventions from the public sector, many of the interventions to reduce emissions will not be possible. An effective progressive just transition will require a well-resourced public service sector. Struggles around the world have shown that it is still possible to make a difference, that human society can transition and be reorganised to protect our planet, and at the same time protect the livelihood of those who inhabit it. That's my message.