Beating the Climate Clock Workers, citizens and state action in the UK

Topics

Regions

This article explores how organised labor, citizens, and the state can play a transformative role in shaping a low-carbon future.

Philip McMaster/Flickr/CC BY-NC 2.0 DEED

It’s April 2020. In the UK, the COVID-19 pandemic was at its height. Ventilators were running out. Prime Minister Boris Johnson was calling for ‘Our Great British Companies’ to come to the rescue and manufacture emergency supplies. Apart from existing producers of ventilators, there was little response. But at the Airbus factory in North Wales, the well-organised Unite branch representing over 4,000 workers, took matters into their own hands and, in a matter of weeks, led the conversion of the factory’s research and development facility into an assembly line producing components for up to 15,000 ventilators for the National Health Service (NHS).

‘Without the union’, commented the Unite convenor, Darren Reynolds, ‘it would have been chaos, lots of problems without any procedure to resolve them. We’ve built up a tried and tested organisation and established procedures for solving them’. He cites the all-important role of workers’ elected health and safety representatives in turning the Welsh government-funded Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre (part of the Airbus site) into an adapted sterile environment. ‘Our 60 health and safety reps have been able to pre-empt the problems and solve them in advance’, he explains.

In this way, 500 Airbus workers, previously producing aircraft wings, turned their skills to producing ventilator parts, meeting social needs, securing jobs, and strengthening their union organisation in the process.

The organisation of the conversion process, the speed at which it was achieved, and the capacity of the workforce to collaborate to meet the challenge, were impressive. This was largely due to the role of the union branch and its shop stewards who organised the aircraft-turned-ventilator workers and their determination to extend collective bargaining beyond wages and conditions to change the product on which they worked.

Moreover, in the context of a crisis in the supply of ventilators to meet the needs of COVID patients, and a call from a Conservative Prime Minister for companies to make them, management could hardly resist the union’s public-spirited efforts to find a solution. Finally, and especially significant for today’s climate emergency, this worker-led experience of successful industrial conversion also offers a glimpse of the potential role of workplace trade unions in moving from a high-carbon to low-carbon economy without job losses. At the very least, the experience points to the importance of a well-unionised workplace for the achieving such a transition.

Efforts to extend collective bargaining to include the purpose of production

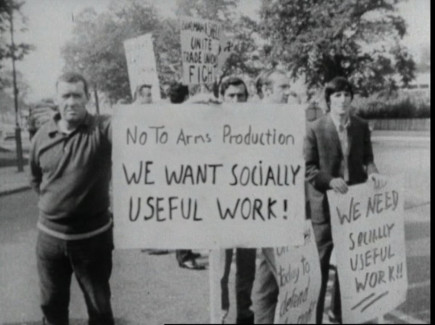

a) The Lucas Aerospace workers’ plan for ‘socially useful production’

A workplace of unionised workers, able to extend the function of collective bargaining, is the exception to the rule in neoliberal post-industrial Britain, after some 40 years of attacks on employment rights and on the very existence of trade unions. In the late 1970s, however, shop floor trade union power, in engineering especially, had gained sufficient strength to question management’s investment decisions, especially those involving factory closures and major redundancies. When corporate management were ‘rationalising’ investments and consequently threatening job cuts and factory closures, they met with organised resistance from workers in the regions and industries most under threat.

‘Don’t Let the North East Die’ was the slogan of a strong regional movement of trade unions and community organisations. Workers from factories along the Tyne – Vickers Engineering, Scott Hunter Ship Building, NEI Parsons – came together with alternative proposals, demonstrating that their skills, far from being ‘redundant’, had socially useful purposes. A similar movement emerged in Coventry, supported by an influential Trades Council, while a group of labour movement researchers brought together shop stewards from the main workplaces of this once thriving industrial city. Here, too, shop stewards’ committees – Chryslers, Alfred Herbert’s Machine Tools, Jaguar, and many more – were defending jobs with positive proposals for the future of their employment. At that time, decarbonisation was seldom, if ever, a consideration. However, energy-saving and pollution-avoiding products were high on the list of their proposals.

These campaigns of the 1970s may only have delayed closures and job losses. But their efforts established a precedent and a collective memory – which can, decades on still be an inspiration, especially when there are few alternatives in current mainstream political debate.

In the aftermath of the pandemic, manufacturing industries, such as aerospace, were slow to recover their pre-COVID levels. But many trade union and green activists drew on the memory of ‘the Lucas plan’ as an inspiration for what could be done and contacted the remaining Lucas Aerospace shop stewards to tell their story. ‘The Lucas Aerospace workers’ alternative corporate plan for socially useful production’ (to give it its full name) was a notably coherent initiative in the 1970s that still reverberates, especially for those attempting change in priorities of production.

Thatcher’s victory and the destruction that it wrought

Before exploring this experience in more depth, we need to stand back for moment. The 1970s was fifty years ago. Fifty years which has been no mere passing of time. Since 1979 the conditions under which workers have struggled simply for their livelihood, let aside control over the product of their work, has become very tough indeed. In 1970s trade unions were at the historic height of their collective strength. Since then they have declined, at least in terms of membership numbers, to the levels of the 1930’s, the decade of poverty and despair.

Thatcher’s government used the might of the state – both its violence and its legal apparatus to wage a determined, ideologically driven class war, against organised labour, the welfare state and local government. Bonds of solidarity and mutuality were pulverised beyond recognition. Today with manufacturing companies controlled by international hedge funds, however, the balance of power between highly mobile capital and fragmented localised labour is overwhelmingly unfavourable. Workers cannot replicate an initiative from the 1970s’ but they can learn from it; it gives them a glimpse of what might be possible.

www.socialistparty.ie

The Lucas Plan: A laboratory for transforming production

In 1978, the Lucas Aerospace Shop Stewards’ Combine Committee produced its ‘alternative plan for socially useful production’. The Combine Committee was the organisation through which shop stewards of different plants of Lucas Aerospace came together to share information and coordinate campaigns for the transformation of production.

The 1970s was a period when UK-based engineering corporations – Lucas Aerospace, Vickers, British Leyland, Chrysler – were attempting to rationalise their sprawling assets with factory closures and ‘redundancies’. Self-confident shop stewards’ committees, increasingly organised on a company-wide basis and with considerable bargaining power – built up during the post-war boom – refused to accept that they and their members, mainly skilled engineers and creative designers, were ‘redundant’. To resist management plans, they not only took industrial action but also proposed alternatives, insisting that management should consider other ways to deploy their skills for public benefit.

Tony Benn, the Secretary of State for Industry in the 1974 Labour government, asked the Lucas Aerospace shop stewards what they thought about bringing the aerospace industry into public ownership. At first, the members of the Combine Committee were doubtful. The experience of previously nationalised industries, like coal and the railways, made them question whether public ownership would necessarily lead to secure employment. They responded instead by drawing up their own plan – in effect, their autonomous terms on which any form of state intervention in the company should take place.

Their plan was based on ideas put forward by union members across the company’s offices and factories and included around 150 medical, environmental, and transport products that these workers believed they could design and manufacture to save jobs – as alternatives to the military components that were the core business of Lucas Aerospace. The shop stewards intended that these proposals should be included in their collective bargaining with management. They hoped, moreover, that, following their discussions with Tony Benn, the Labour government would support their plan, make state funding for Lucas Aerospace Ltd conditional on negotiations on the plan, and shift contracts for military aerospace to contracts for medical and environmental equipment. The Lucas Aerospace shop stewards were, in the words of Karl Marx, demanding that collective bargaining go beyond ‘exchange-value’ (wages and working conditions) to use-value’ (the purpose and products of their labour).

The management declined to consider the alternative plan in labour negotiations. Lucas Aerospace CEO James Blyth, speaking to MPs who had been impressed by the plan and wanted to know why the company refused to engage with it, was obdurate: ‘We do not need the combine committee to tell us to diversify’, he said. The shop stewards had challenged managerial prerogatives. Plus, Tony Benn, contrary to the procedures of the civil service, had made direct contact with and met engineer and designer trade union representatives, on the frontline of production, rather than go through national trade union officials.

Management eventually succeeded in sacking Mike Cooley and Ernie Scarborough, two of the leading Combine members. The Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson moved Benn from the Department of Industry to become the Secretary of State for Energy, and the government finally sided with Lucas Aerospace management, though the union campaign did win a minor reduction in the number of redundancies.

Although the Combine Committee failed in its main objective, its efforts can be seen now as an early attempt at ‘transition bargaining’ or ‘bargaining for public benefit’. The development of the plan and the failure to be able to bargain over its implementation, contain important lessons for today’s challenge of moving to a low-carbon economy.

The final section of this essay asks how trade unions can turn limited industrial power (but advanced practical know-how) into an effective force for decarbonisation.

b) 2020–2024. Rolls Royce aerospace factories: shop stewards’ campaign to produce mechanisms for wind turbines to be in the company’s diversification plans

The decline in aerospace markets during and after the pandemic coincided with increased public awareness of the immediacy of the threat of climate change, in part stimulated by the strikes led by Greta Thunberg and the movement of school students whose futures are at stake. In this context, shop stewards understood themselves as citizens and parents as well as workers and when redundancies were announced at the Rolls Royce aerospace factories, they contacted the local Green New Deal campaign group associated with the Coventry Trades Council. They were eager to learn from the Lucas alternative plan to resist job losses with proposals for alternative, low-carbon, products.

Their company-wide union coordination was not as strong as the Lucas Aerospace shop stewards’ Combine Committee, but they too were confident in the usefulness of their skills and believed that they could and should shift their work from high-carbon aerospace to low-carbon alternatives. The Rolls Royce shop stewards insisted that ‘there is an alternative’ to redundancies, based on the usefulness of their skills to wider society.

As with Lucas Aerospace, management at Rolls Royce were resistant to what they consider to be their right to decide unilaterally on products and investment and the future of the company. But there is a contrast with the Lucas Aerospace experience: the movement for climate action has reached the point where the management realises that the brand’s reputation will be jeopardised if Rolls Royce is not at least seen to be reducing carbon emissions. This vulnerability has given the shop stewards an additional source of strength: the dependence of corporate profits on the reputation of the company brand. The unions were thus able to win a commitment from management, in a written Memorandum of Agreement, to explore products of benefit to the environment if existing employment opportunities came to an end.

Growing anger, most dramatically among young people at the failure of the elites to take action to reduce carbon emissions has also had an impact on workers’ own awareness of their responsibility to future generations, leading some to question their complicity in high-carbon production.

Regional and national strategies

At the same time, although these trade union-led conversion initiatives were emerging in only a handful of manufacturing workplaces, other trade unionists have been working at a regional and national level to create an industrial and political momentum towards a low-carbon economy. The Climate Commissions of Yorkshire and Humberside and of Scotland are among the most notable examples. These two approaches are being linked through the Trades Union Council (TUC), which has appointed staff across the UK (in Scotland, Wales, Yorkshire and Humberside and the East Midlands) to support workplace collective bargaining to reduce carbon emissions.

Thus, a growing minority of trade unionists share an intensifying sense of urgency on climate breakdown. There are also similar tendencies, albeit taking different forms, in France, Germany, Italy and several other European countries. For now, management tend to use their prerogative to block such initiatives, but with the pressing reality of climate breakdown interest continues to grow.

The power of shared practical knowledge, the limits of individual examples

Workers’ collective capacity to control and redirect production makes workplace and regional trade union unionism a vital potential ally for the wider movement to reduce carbon emissions. Simultaneously, this is also what makes these trade union initiatives a threat to management. The transformative potential stems from the power of workers’ practical knowledge of production.

This knowledge tends to be tacit, evident in workers’ skills in making things rather than the codified, written, generalising or ‘scientific’ knowledge that is conventionally – at least in principle and aspiration – the basis of public policy. There is a need for trade-union organising to facilitate the sharing of this tacit social knowledge in order to create a comprehensive ‘under view’ of the production process which can then generate bargaining demands that challenge managements’ overview.

The initiatives referred to so far are at the company level, but the necessary systemic transformation of production to overcome the climate crisis is unlikely to come factory by factory or company by company, especially in today’s global market and financialised capitalism. Moreover, in the UK, the climate crisis has converged with a cost-of-living crisis to a point where workplace unions are overwhelmed by struggles to defend their livelihoods. In such conditions of general austerity, management has the upper hand – which is very different from the post-war boom years during which the trade unions developed their strength.

Even so, there are indications that public opinion in support of extraordinary measures to address either the public health or climate crisis has weakened management’s ability to ensure that collective bargaining remains restricted to wages and conditions. Rolls Royce’s unions resisting redundancies were able to make use of the company’s need to appear ‘green’ to gain a commitment at least to explore low-carbon alternatives.

Beyond telling individual stories: the tools to theorise, generalise and plan beyond existing limits

Thinking theoretically about the obstacles faced by innovative trade unionists helps us to break the repeated cycles of failure and to widen the horizons of our vision. One source of trade unionists’ failure to realise the potential of their leverage over production is that they tend to pass responsibility for issues beyond the workplace to electoral politics, to those they consider to be the representatives of organised labour in parliament.

This abrogation is now particularly evident in the environmental crisis. All too often, trade unions, especially in the UK, pass policy resolutions at their conferences on what the national government could do to mitigate the climate crisis. And, at the same time, they limit their own industrial bargaining to the terms and conditions on which their members sell their capacity to work, regardless of the nature or the purpose of the product.

In order to rethink the relation between workplace trade unionism and economy-wide change (and the potential role of the state in this process) it helps to understand the importance of fossil fuels to the character of capitalist development, especially in the global North. Andreas Malm’s work on the origins of contemporary capitalism is useful here. His study of the Industrial Revolution, Fossil Capital, aims to explain why its entrepreneurial pioneers chose fossil fuel (coal) as the source of the energy to drive production and capital accumulation rather than other sources of energy, most notably water.

Britain’s embrace of coal came relatively late, argues Malm. Water power remained dominant for decades after James Watt’s invention of the steam engine. Fossil capitalism arose from a desire to concentrate industry in cities, thereby avoiding the complex and costly engineering needed to sustain water-powered production in an urban setting. Moreover, the engineering required would have necessitated cooperation and coordination among mill-owners – inimical to most of these early capitalists at a time of intense competition. Coal as a source of energy also allowed for a greater concentration of labour, more easily disciplined, and exploited, before trade unions become established.

Malm’s detailed historical analysis points to the vested interests which protect the fossil-driven energy of the past two centuries of capitalist development with all its cumulative damage to the planet. Whereas Marx’s Capital analysed the exploitation of workers’ capacity to work (that is, to sell their capacity to labour) that lies at the heart of capitalism’s dynamic of accumulation, Fossil Capital analyses the choice of energy and extractive systems to provide the mechanical energy activated by human labour to produce surplus value. In combination, these relationships of class antagonism and Promethean domination of nature led to the carbon-intensive industrial system – and patterns of consumption and habits of everyday life that have built on it for the last 300 years.

A halt and, preferably a reversal, of this process requires transformative action by an actor based in production itself, with a vested interest in or commitment to, cutting carbon emissions, and with a practical knowledge of potential technology of alternatives. Corporate owners and controllers of production are unlikely candidates for such a role (though there are important exceptions). For many shareholder driven corporations the long-term shift to low-carbon production is perceived to jeopardise their profitable assets due to the risks of a shift into unknown (to them) markets, for which they lack easy access to the expertise and sources of sufficiently cheap labour. Moreover, they have made it their business to occupy the key decision-making processes in the state, where they exert their considerable power to weaken the impact of any regulation that might erode their ability to accumulate profit.

Another possible agent, and a constant scourge of fossil-fuel corporations, is the strong activist movement with an explicit, angry and determined desire to end the extraction of fossil fuels – whether the Fridays for the Future school-students’ movement or Extinction Rebellion and its offspring influenced by Malm’s work: Just Stop Oil. These movements have sparked citizens’ awareness and concern on the disaster of climate overheating and he urgent the need for collective action.

The problem with this important ‘end fossil fuel’ movement, however, is that it fails to take adequate account of the large numbers of people whose livelihoods depend on their work in these carbon-intensive industries. Without this, the potential base of a citizens’ movement is divided, with significant numbers having a material vested interest n a high-carbon economy.

To develop a widely shared positive vested interest in a low-carbon economy, we need to consider the transformative potential of the main active, creative agent of production: organised labour. This does not rule out the importance of Extinction Rebellion, Just Stop Oil, Fridays for the Future and other ‘end fossil fuel ‘climate movements and initiatives. On the contrary, these movements and the direct action (however controversial) have helped alert the labour movement to the urgency to reduce carbon emissions and, as we saw in the case of Rolls Royce, have ed them to think critically about what they produce and to act on their obligations to future generations.

The transformative potential of currently alienated labour

According to Marx, labour power is ‘the aggregate of those mental and physical capabilities existing in a human being, which they exercise whenever they produce a use value of any description’. He highlighted the fact that under capitalism, workers ‘alienate’ (or sell) their labour power or capacity to work in exchange for a wage or salary. Workers therefore lose control over their labour power. How their capacity for labour is deployed – to what uses and for what purposes – is the prerogative of capital, responding to the pressures of the market and competition with other capitalists. Trade unions have historically won the right to organise over the terms on which workers sell their capacity to work, that is over the exchange value of labour. They rarely challenge capital’s control over a worker’s capacity to work, the use value of what is produced. The question is how can civic economic actors develop the means by which they control and direct the market to meet social needs?

Beyond exchange value; bargaining over use value

Workers’ initiatives, of the sort with which we began this essay, that aim to convert existing high-carbon production to low-carbon products/ production processes, are challenging this deeply entrenched restriction of trade unionism to bargaining over exchange value. They remain though isolated ‘one-off’ initiatives. Any effective and sustained challenge to commodity production requires such workers’ initiatives to be part of a society-wide alliance able to challenge and replace the market at different levels.

Traditionally the left would have looked to the state to replace the market. And indeed, given the climate crisis, state action will be essential to move society away from fossil fuels. The state though has, as we know been taken over or ‘occupied’ by private capital including fossil capital, especially the oil companies.[1] The strategic problem then becomes how to work both within production (and consumption) the home base for corporations – while also transforming the state so that it breaks from capital and supports organised labour to extend collective bargaining to questions of use value and purpose.

There have been several experiences – albeit local and short-lived – of state institutions led by politicians with a commitment to radical transformation and gaining office in the context of strong and radical social movements. Some of these are international, most notably in cities of Latin America – Porto Alegre in Brazil,[2] led by a radical regional grouping of the Workers’ Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores (PT)), and in Montevideo led by an equally visionary group of activists and intellectuals of the Frente Amplio. We also had an experience in London of which I had direct experience: the four years of the Greater London Council (GLC) 1982-1986 (and its abolition by Margaret Thatcher) at a time when the trade union movement was still confident, and community, feminist, Black and gay liberation movements were hungry for a taste of power, but also resolutely independent.

The story of the GLC illustrates a new vision of the role of the state not as exercising its power of domination in order to centralise power and command but as a resource for organised citizens to realise their power to transform.

Socially useful production versus militarised market production- a municipal political experiment

In the early 1980s, Ken Livingstone’s socialist Greater London Council (GLC), across the River Thames from Margaret Thatcher’s determinedly neoliberal government, pioneered an unusual industrial strategy to address the high levels of unemployment in London. The experiences of the Lucas Aerospace workers were an important influence.

The Labour Party activists and would-be councillors made a commitment to give full support to trade-union alternative plans that shared the objectives of their electoral mandate. The result was the Council’s London Industrial Strategy (LIS), which sought to bring together the local government and workplace trade unionists to guide public investment to maximise public (including planetary) benefit rather than private profit.

The LIS introduction analysed contemporary capitalism as a political economy in which ‘the overriding priority is given to private market production and to the military sector, to increased intensity of work within the factory and the technological replacement of awkward labour’.

‘We can call this militarised market production’, it states. ‘It represents the economics of capital.’ It goes on to argue that ‘there is an alternative, which we shall call socially useful production’. This, it continues, ‘takes as its starting point not the priorities of the balance sheet, but the provision of work for all who wish it, in jobs that are geared to meeting social need’. William Morris, it added, ‘referred to it as “useful work” rather than “useless toil”. It represents the economics of labour’.

There are obviously limits to what can be generalised on the basis of one municipal experience, but we can gain some insights into how state institutions could be transformed to actively support the initiatives of labour for the public good.

The GLC’s achievement was to develop an industrial strategy that sought to nurture the capacity of organised workers, directly and in alliance with community organisations, to transform production more radically than is possible by state intervention alone.

This is not the place for a long digression on the character of the transformative movements at that time. It is enough to say that they were deeply political in the sense of attempting to prefigure radically transformative change, without focusing entirely on the state as its sole or exclusive agent. In this sense they broke from dominant traditions of the left (particularly with strategies that focused almost entirely on the party capturing the state as the agent of change or that delegated agency upwards to the political class).

Creating alternatives in the present to prefigure and prepare for the future

Pre-figurative politics involves the commitment to creating experiences of a new society within, and in conflict with, the shell of the old. Or, to put it another way, it involves organising now to illustrate in practice the values of the society we envision for the future.

The emergence of pre-figurative politics with the social movements of the 1970s, especially the women’s liberation movement was in part a desire to move beyond the instrumental politics of both Leninism and social democracy in which the end – state power through insurrection or elections respectively – justified the means. For feminist activists, the creation of solutions to the day-to-day consequences of their subordination was essential if they were to be active and autonomous.

Setting up community childcare, for example, was very important. Consequently, the early days of the women’s movement saw numerous experiments in community controlled childcare – distinguished from from the state provided and controlled nurseries of World War II. Some of these community initiatives went on to be funded by local councils and became models for public childcare policies, though not without tensions about who was really in control. In this way, a self-conscious pre-figurative culture and social movement can play a part in enriching public policy.

Alisdare Hickson/Flickr/CC BY-SA 2.0 DEED

The impact of neoliberalism on a new left politics

Pre-figurative politics also provides a good description of the work of radical trade-union organisations like the Lucas Aerospace shop stewards or, to give another example relatively common at the time, community organisations resisting property developers and developing their own alternative ‘people’s plans’ for their neighbourhoods. These were often supported by the more radical Labour municipalities.

How this emergent politics could have changed the left’s relation to the state was never fully realised. Certainly, it involved a break from both the social democratic and the command-economy models of socialism, but the implicit positive model remained fuzzy, to be developed in practice as much as in theory.

But political time waits for no one, and time was called by the victory of Thatcher and Reagan and the neoliberal era they inaugurated. The neoliberal offensives of the early 1980s hit the emerging radical left politics hard. Between them, Thatcher, Reagan and an increasingly neoliberal European Economic Community (the precursor of the European Union, EU) destroyed the institutional support for this alternative.

Nevertheless, the glimpses of a radical socialist politics witnessed in the 1970s has remained in the imaginary of a whole generation and shaped movements’ ambiguous ‘in and against’ relationship to electoral politics. The memory has been periodically enlivened by moments of transformative creativity: the transnational, anti-hierarchical networks of the ‘alter-globalisation’ movement; the direct action of the Occupy movement; the anti-racist and pro-LGBT rights movements; and new forms of community organising stretching across these years. These all provide a resource for the kind of movement needed to change the balance of power in the economy and society while building the basis for a different kind of state.

While a shift in the balance of social and economic power is a precondition for transforming the state, a transformation of the political institutions does not automatically follow. On the contrary, these institutions – in our focus those of the UK – often act to protect themselves from the democratic, transformative pressures of movements. In that sense the brief but ultimately thwarted attempt to transform London’s political institutions was an exception; an exception which helps us learn the workings of the rule.

Power as domination and power as transformation

Power as domination – in particular, power through the state – is not necessarily (simply by virtue of being power gained through the state) opposed to power as transformation. It can, for instance, as in the GLC’s popular planning, or Porto Alegre’s participatory budgeting, act as a resource for transformative power: both to support the building of power through enabling it to influence state decision-making and also by providing funds and a platform through which civic or popular organisations can extend and strengthen their autonomous power. This in turn acts as a source of democratic control over the state, notably over the implementation of the manifesto on which the governing party was elected.

This raises the question of the circumstances that make possible a positive dynamic of combined state and popular power. Without going into details, we can draw two lessons from existing detailed studies or reflections: first, that the formal structures /institutions matter in enabling a direct, transparent, interactive and unmediated relationship between citizens and elected politicians. The significance of this, negatively, will become clear when we scrutinise the inadequate democracy of the British state.

The second conclusion is that these formal structures are critical but not sufficient to produce a deepening of democracy and a strengthening of popular power. In both London and Porto Alegre, there were independent animating social forces rooted in society and the economy. In London the animating forces were the grassroots labour movements influenced by the uprisings of the late 1960s and 1970s; in Porto Alegre, it was the Workers’ Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores (PT)) which was able to build on the citizens’ movements built to resist the dictatorship.

So how do we apply these experiences to the combined and concerted state–civic action needed to beat the Climate Clock?

1. Obstacles to change: the institutions of the British state

The British state as it stands is not fit for purpose – to urgently reduce the mounting levels of carbon emissions in a democratic and accountable way against the dominant drive of the private market. Nor will it empower the civic and labour initiatives that share the same goal.

Indeed, British state institutions built since the 1660 restoration of the monarchy are designed specifically to protect the ruling order from any threat to their dominion. Any whiff of insubordination, and they are on the case. This was evident in the alarm and effective exile of Tony Benn, the abolition of the GLC, and the concerted opposition to Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership of the Labour Party and bid to be Prime Minister. Such efforts to marginalise challenging political leaders is made considerably easier by Westminster’s disproportionate ‘First Past the Post‘ electoral system which pushes the electoral process to the centre.

The Scottish writer Neil Ascherson put it vividly when he said, ‘It is not possible to build democratic socialism by using the institutions of the Ancient British State. I include the present doctrine of (parliamentary) sovereignty, Parliament, the electoral system, the Civil Service, the whole gaudy heritage. It is not possible in the way that it is not possible to induce a vulture to give milk’.

Ascherson’s explanation for the fundamentally barren possibilities of change through the British state is highly pertinent: ‘The United Kingdom is still essentially a monarchical structure. Not in terms of direct royal intervention, but as a polity in which power flows from the top down. The idiotic doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty – the late 17th-century transfer of absolutism from kings endowed with divine right to an elected assembly – excludes any firmly entrenched distribution of rights. Popular sovereignty in Britain is a metaphor, not an institution’.

In other words, the key feature of Britain’s state, monarchy, union and all, is that power is exercised from the top down. The people are ruled. They have a vote for their rulers but as subjects rather than citizens. Their rights are limited, especially their right to government information and to call their executive to account. They vote for representatives who swear allegiance not to the people or to the constitution but to the monarch, who is represented in parliament by the Prime Minister. ‘His Majesty’s Government’ is a ritualistic title but it contains a truth – that the executive is not actually accountable to citizens.

And this has significance for the citizens’ possibility of extending their control over the executive when the need arises, as it does in the case of action to slow down global heating. If the principle of accountability to citizens with rights independent of the current executive is not in the legal/constitutional basis of the state, there is no basis on which to expand those rights or ensure that they are implemented.

The contrast the GLC: An oath to the crown versus a duty to the voters

The contrast with the GLC is striking: although historically it tended to imitate Westminster GLC councillors in reality had a ‘fiduciary duty’ (a legal obligation) to London’s ratepayers rather than an allegiance to the crown. Admittedly the relationship of accountability was framed in financial terms, but even so such an accountability laid the basis for policies that strengthened voters’ power – in other words, helped to build power from below. Moreover the Labour Party manifesto had made a strong and explicit commitment to the principle of popular participation as the basis of its intended way of running the GLC. This commitment defined the councillors’ fiduciary duty and strengthened their direct and transparent relationship with the voters, enabling workers to exert pressure and even power over the implementation of the manifesto.

Ultimately, however, the centralised executive power of Prime Minister Thatcher to abolish the GLC, the government of the capital no less, was a sharp reminder that any democracy in local government was dependent on the political whim of Her Majesty’s Prime Minister. In a sense, local government in Britain, lacking any entrenched power, has little more status than the provincial arm of central government, on the imperial model.

2. Possibilities for change: The transformative potential of social and labour movements – a legacy of 1968

An important feature of the 1982–1986 GLC is that the cultural and political hopes and temperament of a significant political proportion of both its political leadership and the leadership of the social and trade-union organisations with which they worked, were also shaped by the 1968 rebellions and the emancipatory movements of the 1970s – feminism, gay and lesbian liberation, Black power, community movements for popular control, shop floor militancy and so on.

Why should these movements of rebellion matter for the struggles of the twenty-first century?

The late Tom Nairn, like Neal Ascherson, a powerful critic of the British state, ‘the whole gaudy heritage’, provides a clue in the book he co-wrote inspired by the ‘événements’ of Paris in May ’68: The Beginning of the End: ‘A humanity which has re-discovered its true height and image without being driven to this discovery by physical need … will never crouch again beneath any fossilised tyranny in the name of order’.

Throughout the 1970s, different parts of humanity strove to reach their true height and image, rising against a variety of forms of subordination and tyranny. Nairn identified with the democratic nationalists of Scotland claiming their right to self-determination against the monarchical Union of the British state. The rise of the women’s liberation movement represented half of humanity striving to reach its true height and image and emphasised, in theory and practice, the importance of self-transformation and of the collective strength to sustain it. To rise from an institutionalised crouch involves a shared collective awareness of possibilities beyond that social subordination and simultaneously an individual aspiration to realise these possibilities and rise to one’s full height.

Self-transformation, direct action and the movement for action on climate change

Self-transformation in the process of a collective struggle also requires a way of organising which realises the capacity and agency of each. This principle has been fundamental to the the movements for action on climate change, such as the direct actions of the Camp for Climate Action against the expansion of Heathrow Airport, Drax B power station and other high-carbon emitters.

Similarly, a small minority of trade unionists have long campaigned for policies to move the economy away from fossil fuels. They came together in 2001 in response to President George W. Bush’s rejection of the Kyoto Protocol to form the Campaign for a Million Climate Jobs. The movement soon became appropriately international and also engaged in direct action closer to home – for example, campaigning against the closure of the Vestas Wind Turbine plant on the Isle of Wight and support for the Vesta workers’ occupation of the factory. This campaign helped to overcome polarisation between the climate and the labour movement by stressing the numbers of public-sector jobs that could be created in providing renewable energy, increasing energy efficiency by insulating homes and public buildings, and hugely expanding public transport. It is an important factor in the growing willingness among trade unions to take action to shift towards low-carbon production in their own workplaces.

The rapid spread of the school student strikes of Fridays for the Future indicate that the spirit of 1968 as a striving for full self-realisation and the end of deference (as identified by Nairn) is still a social force. There is an added urgency though: the need for planetary survival does now play a part, but is given extra force by the angry demand of a new generation for the right to such self-realisation, against a complacent and incompetent elite for which they have nothing but contempt.

Moreover, this challenge to the exiting order takes place at a time when the legitimacy of the ruling order is crumbling from all sides, especially in the UK where neither of the two main parties – neither the Conservatives in government, nor Labour in opposition – enjoy the trust, let alone support, of the public. The powerful impact of a recent TV documentary, ‘Alan Bates versus the Post Office’, an IT scandal and establishment cover-up that saw sub-postmasters wrongfully charged and even jailed and the impressive resistance of the 500 or so sub-postmasters and mistresses that it featured, is a strong illustration of how the reserves of deference on which the legitimacy of Westminster and Whitehall depended, have run dry.

Movements, however, also need material resources – they can’t survive on self-confidence, creativity and solidarity alone. The movements of the 1970s, despite their spirit of autonomy and self-reliance, often depended on public resources, such as the voluntary labour of supportive academics and the activists and artists who lived on public benefits. Some even directly received public funding. Despite this paucity of traditional sources of material support there has not been an end of actions – on the streets and in the workplaces – for lower carbon emissions. The urgency of the issue has produced dynamics of openness to alliances that break down traditional boundaries and a growing willingness to improvise to pre-figure elements of a low-carbon economy in daily life with local insulation, renewable energy projects, alternatives to agroindustry and so on. Groups are also adept at finding material support from what’s left of the public sector – universities, local government, local ‘anchor institutions’ such as colleges, hospitals, police and schools – to use, for example, their procurement powers to support local co-operatives, social and environmental enterprises.

The important point is that there is a movement that has the potential to transition to a low-carbon economy with the strength to sustain itself and achieve partial victories independently of a supportive state. This movement could also prepare the way, shifting the balance of power, to make such a supportive state possible. In the absence of any immediate hopes of a political breakthrough, the movement will need to find political allies wherever possible – sometimes local councils, sometimes a rare Labour MP who champions their cause; sometimes support from other political parties – the Greens, SNP and Plaid Cymru.

Like the Airbus workers who took the initiative to convert aeroplane parts to ventilator parts, these alliances are organised independently of any political party but can take effective political action when the need and opportunity arises. Moreover, the transformative power that they build in the economy and in society can help shift the balance of power to challenge the corporate capture of the state that has so far blocked any radical political leader from gaining and holding on to government office. Such a vision implies a long-term strategy, but one which potentially wins changes on the way. An extension of collective bargaining over the purpose of production along with actual working micro-examples of low-carbon production are essential to saving the planet at a time when political elites continue as if the Climate Clock no longer ticks.