“All Roads Lead to Jerusalem” A Lucrative Border Industrial Complex

Topics

Hebron, a laboratory for both technology and violence, reflects the Israeli occupation's impact on daily life, with sterilized roads, military checkpoints, and settler violence defining the landscape. This journey unveils the complex layers of trauma, dispossession, and dehumanization, challenging preconceptions and raising questions about freedom and oppression.

Petra Molnar

We are staring down at the barrel of an automatic rifle, held by a nineteen-year-old. This soldier is one of three giving us a private “escort” through the occupied city of Hebron in the West Bank of Palestine. In the spring of 2023, my colleague journalist Florian Schmitz and I are guided by a group of former Israeli soldiers who started the group Breaking the Silence in March 2004 to shine a light on the countless atrocities perpetrated by Israel in Palestine. They kindly offered us a private tour of Hebron so we can see the impacts of surveillance firsthand. “Hebron is the laboratory for technology but also the laboratory for violence,” says Ori Givati, a former Israeli soldier who used to serve in Hebron and is now the advocacy director for Breaking the Silence. The Israeli occupation of Palestine has been a breeding ground for technologies like drones, facial recognition, and AI-operated weapons—technologies that are exported and repurposed around the world.

Petra Molnar

We set off from the settlement of Kiryat Arba, on the outskirts of Hebron—one of the areas that the occupying Jewish settlers have claimed as their own. Israel has been moving quickly to occupy more and more land, separating Palestinian territories from each other. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Hebron, which is now divided into two territories: H1, under Palestinian control; and H2, under the control of the Israeli military. If you are a Palestinian, what would have been a two-minute walk to your grandmother’s house now takes you an hour because you have to avoid certain “sterilized roads” that are made inaccessible to Palestinians. Sometimes you have to ask for permission just to cross the road to the cemetery to bury your dead.

“Sterilization” is a strange term for the Israeli state to use. Before driving through the West Bank, Florian and I had visited Yad Vashem, the massive Holocaust memorial in Tel Aviv, carved into a mountain overlooking the booming capital. Room after room is filled with artifacts of the Holocaust—toys, letters, torture instruments, and photos of some of the millions who were brutally murdered. Medical instruments for forced sterilization and phrenology, or the study of supposed racial inferiority based on human skull and facial shapes, make me immediately think of the new appetite for the phrenology we see now in the growing obsession with facial recognition, boiling us down to easily analyzable data points.

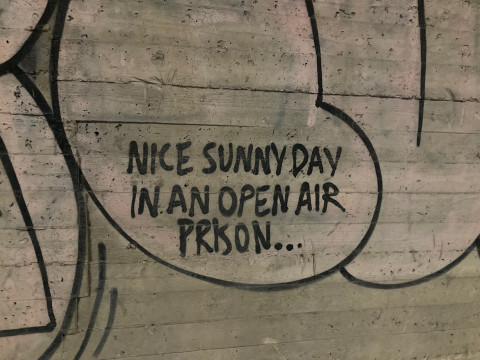

Hebron is a haunted ghost town. What were previously bustling streets full of life are now patrolled by armed Israeli guards, many of them barely older than children. As we walk, we pass a group of twenty teenagers, who could not have been older than sixteen or seventeen. Future army recruits, we are told, each with a machine gun, marching through Hebron. Farid Esack, a South African survivor of Apartheid, once visited Palestine and reflected on the similarities there to South Africa. His open letter to the Palestinian and Jewish people is worth reading in its entirety, but one line in particular struck me: “We do not deny the trauma that the oppressors experienced at any stage in their individual or collective lives; we simply reject the notion that others should become victims as a result of it.”1 This is perhaps why the violence, dispossession, and dehumanization in Israel fundamentally changes you when you see it firsthand, especially when you reflect on the very real generational trauma of the Holocaust and the antisemitism that reverberates to this very day. As Florian, who is German and has been reporting on antisemitism, put it, “If you oppress someone, are you ever really free?”

The settlers first came to Hebron under the pretense of celebrating Passover in 1968, and they never left. Hebron now has twenty-three military checkpoints. There are active patrols all over the city, with around 650 soldiers serving to protect 800 settlers—around a thousand on weekends—all equipped with cameras and surveillance equipment. Breaking the Silence tells us that there are also “extraordinary” missions to provoke Palestinians into violence. According to Ori, “Settler violence is Israel’s policy. The state wants to make it look like Palestinians are violent and must be controlled, so soldiers are sent in to protect them.” And violence will be met with violence and with the construction of further settlements. I am reminded that when settlers come to take the house of a Palestinian family, they are sometimes forced to self-demolish the home to avoid paying a massive fine to the Israeli government.

As we wind our way through the cobblestone streets, a small car drives by and a woman settler films our small group with her cell phone, waving a familiar hello to the soldiers. She trails us for a while before speeding off. We climb a hill of broken stones to meet with Issa Amro, a Palestinian activist who runs a community center out of his house, a meeting hub right next to a military checkpoint. We can see the soldiers looking on as we have our coffee and snacks under the shade of a massive olive tree. On the opposite wall is a painting of the red, white, black, and green map of Palestine. Issa had been brutally assaulted by Israeli soldiers the week before while walking around with a Washington Post journalist. The violence was captured on video, which immediately went viral. He wears an army jumpsuit and a Che Guevara–esque cap and his behavior is confident, although occasionally betraying the awareness that he may be Hebron’s number one persona non grata. And he is obviously not the only one to be harassed and assaulted. The settlers in Hebron regularly assault children, throw garbage on Palestinian homes, and make the lives of Palestinians unbearable on a daily basis. In fact, while we were there in February 2023, a raid in Nablus killed at least eleven people, including teenagers and a grandmother. In a separate incident, Israeli settlers shot a Palestinian man. As Issa says, “When you’re scared to walk out of your front door and know you will be attacked, you prefer to move away.”

Petra Molnar

Israel’s ongoing repression of Palestinians and the occupation of their territories for more than half a century has been publicly called a system of apartheid, not only by Israel’s leading human rights group, B’Tselem, in its 2021 report, but also subsequently by international groups like Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International. One way that Israel is able to maintain these violent policies is through the surveillance technology that permeates every facet of Palestinian life. As the former Israeli soldier Ori told me, “How do we control the Palestinians? We make them feel like we are everywhere. We are not only invading your home but also your private digital space.” Indeed, privacy is virtually nonexistent in a place like Hebron. Cameras point into every bedroom, and courtyards like the one we sat in as we spoke with Issa are installed with long-range video and audio surveillance equipment. We wave hello, just to be polite. Issa has in turn been giving video cameras to Palestinians, as a way for them to be able to turn the lens on Israeli soldiers. He also has many installed in his house as a form of protection. But these cameras are no match for the vastness of the Israeli surveillance infrastructure. Israel controls Palestinian Wi-Fi, installs cameras on nearly every lamppost—some even disguised as rocks in farmers’ fields—and employs a vast network of biometric surveillance, including facial recognition cameras at checkpoints. Israeli settlers are now being equipped with their own drones by an Israeli company that publicly presents itself as an NGO. Meanwhile, AI-operated guns are mounted at checkpoints.

Petra Molnar

One night, we head back to Issa’s house from our hotel in H1, where we seem to be its only guests. Florian drives us through the maze of Hebron’s streets while Issa navigates via a patchy video link: “Left, left, now to the right, watch out for the goats.” When we pull over as instructed, a young Palestinian man startles us by jumping into the back seat. He quickly explains that his name is Ahmad, he is an activist, and he is there to help us with the rest of the extremely complicated way back. We would have to avoid the “sterilized” roads that he is not able to be on as a Palestinian.

Petra Molnar

Back at Issa’s house, we sit next to a fire roaring in an old oil drum. Ahmad and the other men cook us chicken and prepare coffee, with the sound of the azaan, the call to prayer, reverberating over the hills—an auditory reminder of Palestine in this divided city. Living in Hebron his whole life, Ahmad is no stranger to surveillance. “They check us by the eyes,” he says. “They stop us one hour or three hours for nothing. 20055 . . . My number is 20055 at the computer. We are numbers, we are not humans.” I can’t help but think of Yad Vashem.

Since our visit throughout the West Bank in the spring of 2023, Israel has launched a brutal operation against people in Gaza, relying on various technological tools to aid in its mission to target as many people as possible. These days a new gospel is coming from the Holy Land. The Gospel, an AI system deployed in Gaza helps generates new targets at an unprecedented rate, using artificial intelligence to optimize its operations. 18,787 Palestinians have been killed since October 7, 2023 (www.aljazeera.com 15 December 2023).

Petra Molnar

Israeli Eyes Turn Outward

Israel is at the center of much of the world’s surveillance technology that is normalized and tested out on Palestinians.2 One of the leading players in border surveillance and spyware, for example, is the Israeli company Elbit Systems. Headquartered in Haifa and started in 1966, Elbit Systems expanded from weapons logistics to become a surveillance powerhouse of nearly eighteen thousand employees worldwide with a revenue of $5.28 billion in 2021. Elbit Systems’ flashy demonstrations make frequent appearances at various conferences like the World Border Security Congress, with the company’s cheery yellow logo hiding a business model that Israeli writer Yossi Melman describes as “espionage diplomacy,” which tests out surveillance technology both at the border and in conflict zones, often turning its eye on those trying to document what is happening on the ground. Elbit Systems is Israel’s biggest defense company, but much of its technology is also used for border enforcement, from armed autonomous surveillance drones like the Hermes, first tested out in Gaza, which now patrols the Mediterranean Sea, to the fixed AI surveillance towers sweeping the Arizona desert.

For anyone working in this space, names like Elbit send chills down their spine, as does the NSO Group—also Israeli—arguably the world’s most successful cybersurveillance firm. Since its founding in 2010, the NSO Group has cemented its global hold through its stellar surveillance capabilities, notably with Pegasus, its flagship surveillance application for spying used by governments from Saudia Arabia to the United Arab Emirates to Greece. Pegasus infiltrates mobile phones to extract data or activate a camera or microphone to spy on owners. The company says the tech is designed to fight crime and terrorism, but it has been found by investigators to have been used on journalists, activists, dissidents, and politicians worldwide. The NSO Group has been implicated in human rights abuses all over the world, including the brutal murder and dismemberment of Saudi journalist and political dissident Jamal Khashoggi in October 2018.3

The NSO Group also turns its eyes inward, to residents of Jerusalem and other cities. At least six Palestinian human rights activists have been hacked, including two dual nationals, one French and the other American, like French-Palestinian Salah Hammouri, a lawyer and field researcher at Addameer Prisoner Support and Human Rights Association, based in Jerusalem.4 Making life difficult for anyone doing work on these issues, even Israeli activists, seems to be the prerogative. Ori and his colleagues at Breaking the Silence are routinely harassed and interrogated, and some have even been arrested. When asked about the likelihood of spyware on their phones, they shrug—it seems to be par for the course. Even Florian and I take extra precautions, uploading all our photos and audio to an encrypted cloud system and wiping our phones clean. It still isn’t enough, though, as we are thoroughly interrogated at the airport on our way out, my suitcase picked over. It contained an “incriminating” cookbook, children’s toys, and a few leaflets from a human rights organization, which the airport security agents used as evidence of our presence in the West Bank. After our passports were confiscated for what felt like an eternity and more persistent interrogation, our documents were handed back with a flourish and an invitation to “come back.” At least this time, we didn’t have to hand over our phones.

Other examples in this network of surveillance include the Israeli company Cellebrite, a firm marketing itself as the “global leader in digital intelligence,” which advertises its devices to authorities interrogating people who are seeking asylum.5 First founded in 1999 and now a subsidiary of Japan’s Sun Corporation, Cellebrite markets forensic tools that empower authorities to bypass passwords on digital devices, allowing them to download, analyze, and visualize data. There is now also a physical, high-tech securitized wall in Gaza, which was completed in 2021 with construction assistance from Europe at a cost of $1.1 billion. Both construction and security firms were involved in erecting the wall; Elbit Systems’ surveillance contributions included robots, drones, and unpiloted ground vehicles. All the devices are equipped with visual, electronic, and intelligence equipment and powered by AI, operating through command-and-control bases along the barrier.6 There are also many other, less well-known players and Israel also operates increasingly vast databases on nearly every Palestinian. The Blue Wolf app came first, downloaded to Israeli soldiers’ phones in Hebron to record information to identify people like Issa Amro and Ahmad as they make their way through various checkpoints in the occupied city. According to Breaking the Silence, surveillance has become gamified, with soldiers incentivized to register as many Palestinians as possible, keeping them under constant observation. In 2022, Amnesty International and local digital rights groups like 7amleh found that the Blue Wolf app has been augmented by Red Wolf, a CCTV camera system using AI-driven surveillance tools including facial recognition. The software uses a color-coded system of green, yellow, and red to guide soldiers on whether to let the person go, stop them for questioning, or arrest them.

Petra Molnar

Armed technology is also on the rise in the West Bank. Companies like Smart Shooter have deployed AI-powered guns in places like Aroub refugee camp in the West Bank that can track targets to enhance accuracy when firing tear gas, stun grenades, and sponge-tipped bullets. Another company, XTEND, boasts that its virtual reality training technology is so effective, soldiers “within 10 minutes . . . start downing balloons in the Gaza Strip.” Powered by the Skylord operating system, the technology boasts a “revolutionary micro-tactical Intelligence Surveillance Reconnaissance platform, with built-in resilient indoor-outdoor navigation and AI capabilities,” all aimed at Palestinians.

Petra Molnar

The XTEND technology was also tested in Arizona. And it is not the only Israeli technology used there. In an investment over ten years totaling at least $500 million, the United States has installed at least fifty-five fixed AI-system surveillance towers made by none other than Elbit Systems. It has been contracted by the U.S. Border Patrol to put Native American reservations along the Arizona border under constant surveillance, including through surveillance cameras and drones.7 This technology was first rolled out in the surveillance sensors for Israel’s separation barrier through the West Bank, a barrier the International Court of Justice ruled to be illegal way back in 2004 but still stands today.8 The European Union’s appetite for Israeli surveillance has also exponentially grown as it tries to wall itself off from further “undesirable” migration. The Observer and Statewatch also uncovered various contracts to track migrant boats reaching the shores of Europe. The agreements, negotiated between Elbit Systems, the European Union’s Frontex, and the European Maritime Safety Agency, total $115 million.

However, this AI and surveillance technology flows in multiple directions. In one notable example, Google, Amazon, and the Israeli government signed a $1.2 billion contract for Project Nimbus, providing advanced artificial intelligence and machine learning technology to the Israeli government, which could augment the country’s use of digital surveillance in occupied Palestinian territories.9 This, while the West Bank is in the middle of some of the worst violence and apartheid repression in decades. The contract provoked anger among both Jewish and Palestinian Google employees, who have publicly spoken out about the project. Some, like computer scientist Ariel Koren, have been fired; some have resigned. Others have been silenced.10

Petra Molnar

Outpost Border Guards

Bordering is a practice. In Israel and Palestine, you can see this practice of division and dehumanization enacted daily. The creation and recreation of this division is more dynamic than rigid understandings of borders would seem to indicate. Physical walls, for example, can be expanded to hem people in, but when coupled with a vast, increasingly automated surveillance infrastructure, the border can be made to extend well beyond a dotted line on a map or a crossing point separating one state from the next. Raluca Csernatoni, an expert on European security and defense, evocatively writes that “the increased use of drones to police borders has resulted in the decentralization of the border zone into various vertical and horizontal layers of surveillance, suspending state power from the skies, and extending the border visually and virtually.”11 As Professor Ayelet Shachar writes in her book The Shifting Border, “Our gates no longer stand fixed at the country’s territorial edges. The border itself has become a moving barrier, an unmoored legal construct.”12 One of the ways that borders have been shifting is a phenomenon called “border externalization,” or the transfer of border controls to foreign countries.

Surveillance technology is central to this. Technologies that manage migration, whether retinal scans or automated AI lie detectors at airports, all collect data, make decisions, and report to the state the necessary information on potentially unsafe migrant bodies, rendering them into security objects and data points to be analyzed, stored, collected, and rendered intelligible. And in an environment of narratives emphasizing risk, terrorism, and the need to keep Western countries safe, new forms of control emerge. For journalist Antony Loewenstein, author of the award-winning book The Palestine Laboratory, this is yet another instance of “digital orientalism,” echoing the work of Palestinian theorist Edward Said—treating certain groups with suspicion by definition while others are welcomed with open arms.13

Countries with the largest defense and security sectors, such as the United States, Israel, and China, are transferring this technology and these practices to governments and agencies around the world. The same goes for multilateral organizations such as the European Union. The Transnational Institute (TNI) itself has been working on these issues for decades, thinks about externalization as a “carrot and stick” approach, creating financial and policy incentives for third party actors, and often poorer nations, to push established borders further and further from their geographic location.14 Often framed as cooperation, externalization replicates power hierarchies, with impoverished countries like Niger doing the dirty work of the EU to stem migration, sometimes with Israeli surveillance technology. As writer and activist Harsha Walia reminds us, these practices work to perpetuate border imperialism, where powerful actors like the United States and the European Union wield tremendous geopolitical power and financial influence over countries in Latin America, Africa, and the MENA (Middle East and North Africa) region. Shameful imperial and colonial histories play out in new ways, simultaneously causing mass displacement and actively working to stifle it. A greater number of people on the move that apparently need to be controlled means more lucrative high-tech projects for the private sector to develop.

Israel is a major player here, with Israeli security companies among the most successful—and profitable—in the world. The country’s world-class weapons industry is consistently tested out on Palestinians and then marketed as “battle tested”; consequently, as journalist Antony Loewenstein argues, “the Palestine laboratory is a signature Israeli selling point.”15 Israel has actively supplied weapons to myriad repressive regimes, including South Sudan, the Ceauseşcu regime in Romania, the Assad regime in Syria and Russia’s military support for the regime, Sri Lanka, and the Duvalier regime in Haiti, among many others.16 Elbit’s Hermes drones are even patrolling the Canadian Arctic for environmental monitoring. And right after the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Elbit stocks rose by 70 percent—war is indeed profitable.17

One of the reasons why externalization works is that it plays into the global weakening of international norms that protect the right to seek asylum. In a complicated geopolitical reality where people on the move who are seeking protection are caught in the middle—without access to lawyers, humanitarian aid, or even doctors—people who have the right to seek safety are actively prevented from being able to do so. Powerful countries band together in a performance of common victimhood, falling back on blatant Islamophobia and racism against African migrants and Muslim “invaders” in particular to justify increasingly hard-line policies of surveillance and exclusion. Australian journalist Antony Loewenstein, who has spent years documenting surveillance technologies used against Palestinians, argues in his 2023 book The Palestine Laboratory that the threat of being overrun justifies experimentation, often first in Israel and then in US and the EU. These are not new ideas. In the 1980s, cultural theorist Stuart Hall cautioned against authoritarian populism, which often stokes fears around immigration, terrorism, crime, and left-wing subversion.18 This brand of populism contributes to the increasing normalization of technology as a mechanism of control and, more specifically, as an antidote to being overrun by the unwanted and dangerous—a way to see, control, monitor, and exclude. We must also pay attention to particular sites of experimentation that center on groups with fewer protections available to them, such as people in experiencing humanitarian emergencies or encountering the migration management bureaucracy. Surveillance capitalism, meet disaster capitalism. Migration data is already being politicized to justify greater interventions in support of threatened national sovereignty, weaponized by far-right groups that continually wage wars on migration. And the private sector, meanwhile, stands to make a quick buck.

Journalist Todd Miller and others have been writing about the rise of a multi-billion-dollar border industrial complex, the confluence of border policing, militarization, and corporate investments.19 This industry is fast and growing, projected to have a total value of around $68 billion by 2025—higher than the annual GDP of most countries—with the largest increases in global biometrics and AI projects.20 Big money is involved in the management of borders, as private security companies make major inroads with lucrative contracts, procured by governments, for shiny new tech experiments presented as the only surefire way to strengthen border security.21 From vast private prison complexes on islands like Nauru and Christmas Island, where Australia sends its asylum seekers, to American company BlackRock, the world’s largest asset management company, being a major shareholder in eleven border and surveillance industry companies.

The private sector is in charge of much of the development of new technologies, and states and governments, wishing to control the flows of migrant populations, benefit from these technological experiments. This type of experimentation also shows whose interests matter most, as states prioritize and legitimize the types of interventions peddled by the private sector at conferences like the World Border Security Congress in the form of increasingly disturbing tech “toys” like drones, robo-dogs, and radars.22 In an ongoing global war on human movement, states prioritize these tools instead of funding solutions to combat racism at the border or improve fairness in asylum proceedings. All these technological experiments are situated in a broader historical system of control, bolstering a lucrative industry where private sector players set the agenda with virtually nothing by way of meaningful governance and oversight. Furthermore, the private sector is often the first to oppose any regulation or oversight, stating concerns about the stifling of innovation and the infringement on the fulfillment of Silicon Valley fantasies. The aim is a free-for-all in the sandbox of tech development, a techno-solutionist utopia, opening up spaces of unrestricted tracking and surveillance.

Move Fast and Break Things

The reason for many governments’ over-reliance on the private sector is a lack of adequate technical capacity within the public sector, even though adopting emerging and experimental tools without understanding, evaluating, and managing these technologies is irresponsible and downright dangerous. The result is that private corporations hold the balance of power when determining what technology is developed, deployed, and subsequently procured by governments.

Intellectual property laws and proprietary considerations also hide how exactly much of the technology operates, creating a vacuum of accountability. The private sector also plays into this confusion, not releasing information, obfuscating debates, and lobbying behind closed doors in order to prevent regulation and any impediments to innovation that could be seen as diminishing profit.23 With many large and lucrative technology projects there are strong commercial incentives for vendors to impose licensing conditions that keep source code closed and unavailable for public scrutiny. And to increase profit even more, vendors may be interested in using data provided by government for commercial purposes beyond the government’s own.

Relying on the private sector also has its benefits for states by watering down liability and accountability. Governments can disavow responsibility for mistakes since they aren’t the entities developing the tools. States deliberately rely on the private sector to ensure technological experimentation occurs outside the realm of sovereign responsibility, thereby depriving people on the move of the rights and protections enshrined in domestic and international law by invoking the private sector’s insistence upon discretion regarding proprietary technology and other private interests.

As Loewenstein writes: “When, in 2016, privatized security guards killed twenty-four-year-old Maram Salih Abu Ismail at Qalandia checkpoint [between the northern West Bank and Jerusalem] alongside her sixteen-year-old brother Ibrahim Taha, nobody was ever held accountable. Israel’s shoot-to-kill policy becomes even more widely applied when the so-called security services are outsourced. That is exactly the point, because when an abuse occurs the state blames the private company for the crime.”24 But where does this leave the people affected by these technologies?25 Decision-making regarding which technologies to implement often happens without consultation, much less consent, of the affected groups, as when refugees must have their irises scanned in exchange for weekly food rations inside refugee camps.26

Petra Molnar

These monopolies of knowledge and power, which vest authority in powerful actors like the private sector and states, exist precisely because there is no unified global regulatory regime governing the use of new technologies, creating perfect laboratories for high-risk experiments.

Technological experiments in migration are justified because people on the move have been historically made into a population that is intelligible, trackable, and manageable.27 The very rhetoric of migration “management” implies that refugees and migrants must be presided over and controlled, as they are construed to be a threat to national sovereignty, particularly in times when more and more states are turning inward. When sovereignty is under threat, the state justifies its control over populations through continuous messaging about necessary national security and border control, and public spectacles that enforce that messaging.28 This performance is particularly far-reaching when the law is suspended, such as in Australia’s extraterritorial (and extra-legal) immigration detention policies, or, as in the case of technological development, where there simply is no (or very little) law.29

The private sector likes to forget that it already has an independent responsibility to ensure that technologies do not violate international human rights law, such as under the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.30 In the development of products and services, private entities also have clear legal obligations to comply with domestic law, including privacy and human rights legislation. Technologists, developers, and engineers responsible for building this technology also have special ethical obligations to ensure that their work does not facilitate human rights violations.31 But there is an overall lack of institutional capacity to effectively regulate technology, as well as a disjuncture between those who develop migration-related technology in the private sector and those in the public sector who deploy it on specific populations. The so-called AI divide, or the gap between those who are able to design AI and those who do not, is broadening and highlights problematic power dynamics in participation and agency when it comes to the rollout of new technologies.

The private sector is not the only major player in these demarcations of power and privilege. Non-state actors, such as the UN, perform this role as well. The United Nations, too, can easily succumb to the Israeli security sector’s siren call as the number one expert in surveillance technology, announcing in 2020 that Mer Security, Elbit, and Israel Aerospace Industries had won contracts to provide security for UN bases in Mali, including the installation of CCTV cameras, drones, and threat detection systems. The UN was lobbied aggressively by Israeli companies to secure similar work at the forty peacekeeping bases throughout the world.32 Much of migration management is also practiced and enacted by international organizations such as UNHCR, IOM, and various other bodies, who have a profound influence in shaping decisions concerning technology. As they are often the first on the ground following a humanitarian disaster, they also set the agenda in terms of prioritization when it comes to humanitarian innovation and technological development.33 But as non-state actors operating under various legal and quasi-legal authorities and regulations globally, international organizations are “arenas for acting out power relationships” without being beholden to the responsibilities that states have to protect human rights.34 States that operate through international organizations can also “launder” their legal responsibility, as they do vis-à-vis private corporations, by attributing acts or omissions to the organization instead of themselves or other states.35 International organizations are thus overly empowered to administer technology without being beholden to rights-protecting laws and principles.36

For example, international organizations such as UNHCR are taking the lead on the identification and tracking of migrants and refugees. At first glance, digital identity technologies would seem to meet a pressing need: UNHCR states that in today’s modern world, lacking proof of identity can limit a person’s socioeconomic participation and access to services, including employment opportunities, housing, a mobile phone, and a bank account. But there is inadequate attention to the possibility that technologies, because they rely on identity data, may exacerbate existing biases, discrimination, or power imbalances.37

Israel is also turning on its own people. In the spring 2023, vast reforms by the Netanyahu administration threatened to allow Israel’s parliament, the Knesset, to overrule any decisions made by Israel’s Supreme Court. This administration is the most far right in Israel’s history, with close ties to the settler movement and Israel’s ultra-religious community. In a never-before-seen show of opposition, thousands took to the streets in Israel, including moderate Israelis flying in from Canada and other countries. Ongoing protests risk an ever-widening split in Israel between the growing power of Zionism and a more liberal secularism. All the while, pogroms by Jewish settlers continue in the West Bank, including the February 2023 burning of Huwara, a small village close to Nablus. Stopped by an armed checkpoint and unable to visit Huwara, Florian and I pulled over on the side of the road in Ramallah to pick up some strawberries, one of the only exports allowed from Gaza. I stuck their little round red label that says “فلسطين ، غزة الإنتاج (Palestine, Gaza Production)” on the back of my phone. Many things still grow under occupation.

Petra Molnar

But will these strawberries survive Israel’s systematic onslaught of Gaza? After the attacks and incursion outside the Gaza strip by Hamas on October 7, 2023, Israel’s complete siege of Gaza, including the targeting of hospitals and humanitarian corridors, showed a level of violence so unprecedented that it may meet the international legal definition of a genocide, or at the very least a war crime and ethnic cleansing.38

What will these seismic shifts mean for the future of Israel—and the future of Palestine under occupation? With the shekel taking a nosedive, and investors pulling out from Tel Aviv, the surveillance and arms industry is going to have to work overtime to generate revenue. Luckily, the Israeli weapons and surveillance market has a long history of success in this area—selling “battle tested” weapons and state-of-the-art border surveillance after thoroughly testing them out on Palestinians in the laboratory of the West Bank and Gaza.