Ideas into movement

Boost TNI's work

50 years. Hundreds of social struggles. Countless ideas turned into movement.

Support us as we celebrate our 50th anniversary in 2024.

Every city seems now to be looking for its 'Silicon Valley'. But what's the reality for cities that embrace Big Tech? Exploring two-case studies in Dublin, Ireland and Kitchener-Cambridge-Waterloo in Canada, this essay explores how urban space and public policy is transformed by digital corporations and how the allure far exceeds the concrete benefits.

Walking along Dublin’s River Liffey, one sees a stark contrast between the historic city centre and development along its eastern edge before the river meets the Irish Sea. Whereas the city centre comprises compact buildings in brick and stone, those in the grid of the North Lotts and Grand Canal Docks are made of exposed steel beams and expansive glass façades.

Here, the neon lights of the Kevin Roche’s convention centre reflect along the Liffey, casting a bright rainbow on Santiago Calatrava’s Harp Bridge. Particularly in marketing brochures, and also on Google Maps, this shiny section of Dublin has come to be known as the Silicon Docks.

Formerly the site of maritime activity and warehouses to store goods and shipping material, it is now the privileged neighbourhood for some of the world’s largest tech companies. Accenture, Airbnb, Facebook, Google, LinkedIn, and Twitter are just a handful of those currently based there and taking advantage of Ireland’s tax-avoidance schemes. It is also the ‘live-work-playground’ for the new class of tech workers.

Kayanan, 2019

The modern corporation, especially in knowledge-intensive industries, has created a narrative in which the ideal worker is the innovator, the disruptor, the so-called ‘creative’ individual – the start-up tech entrepreneur. A significant component of this trope is that the industries sell themselves as the ideal workplace where such individuals can thrive, from tinkering in the proverbial garage to managing a multibillion-dollar corporate estate.

We have seen corporations do this before: from the industrial economy with the factory as its spatial counterpart, in which the blue-collar worker struggles at centre stage, to the information economy with its the skyscraper office building, where white-collar workers reign supreme. Changes in the landscape of work are inextricably linked with changes in work and work culture. In today’s digital economy, this innovative and creative disruptor is a no-collar – neither blue nor white yet somehow both – wireless worker, who needs both the office and the city in order to be both productive and entrepreneurial. While the work is predominantly cognitive, and therefore technically white collar, tasks can be routine and mechanical, and productivity is monitored and measured every step of the way.

St. Louis’ Venture Café

Embedded in this new class of worker is the promise of progress: profit and growth for corporations, cities, and individuals alike. The projected benefits are meant to be all-encompassing and all-inclusive: better jobs, greater purchasing power, investment in infrastructure, and a reserve army of tech-saviours. In the process, the influence of the modern corporation is less visible than before, but still lies under the surface. It finds its mouthpiece in the public sector and its oasis in public funds. The public sector is willing to bend its own rules and amend plans to transform spaces – public and private – to suit the needs of the corporation. And the general public, also captivated by the alluring narrative, allows it. There is, however, an undercurrent of intense competition for global city status, giving corporations the freedom to pick where to locate and which talent to exploit. This results in many newly transformed spaces that are underused and overvalued, exclusive and empty.

Pajević, 2019

The current hype for ‘disruptive innovators’ seeks to create a vibrant and buzzing innovation district in countless workplaces and surrounding cities worldwide, almost all of them branded ‘silicon’ – Silicon Mountain in Cameroon, Silicon Valley North in Canada, Chilecon Valley in Chile, Silicon Valley of India in Bengaluru, Silicon Wadi in Israel, Silicon Gulf in the Philippines and Silicon Cape in South Africa.

Kayanan, 2019

Buildings, their surroundings, and the street vibe need to be attractive to the no-collar class. The architectural grandeur, spatial configurations, and wealth of amenities of tech campuses such as Apple, Facebook and Google speak to a utopian imaginary and feelings about contemporary working life. The designs of these corporate estates declare that the work that is taking place within their walls is exciting, innovative, cutting-edge, and impactful. It is through these symbolic spatial dimensions that corporations assimilate themselves into and promote the values of an increasingly dominant tech culture.

Often, despite seeking to plan for inclusive design, the spaces surrounding these Silicon Valley wannabees remain eerily silent. When Big Tech establishes urban amenities within its buildings, it removes the buzz from the city streets. Google employees notoriously rarely leave their grounds. Why should they? Google has a gym, a shuttle bus, and even its own chef! Employees are safely cooped up in their offices, while the city struggles to look alive. This also happens when corporations occupy an area or a neighbourhood: the many layers of security and surveillance that are critical for Big Tech work to remove any ‘undesirables’ from the area and ensure surroundings are conflict-free zones for business to proceed as usual. The modern corporation expands in order to enclose.

In this essay, we discuss how the city is transformed, using public funds, to cater to the modern corporation and how the promise is more often than not better than the reality. We focus specifically on Big Tech in two cities that have been reconstructed – Dublin, the capital of Ireland and Kitchener-Cambridge-Waterloo (KCW) in Canada – both marketed as home-grown versions of ‘Silicon Valley’.

‘Be Bold’, Facebook’s career homepage declares, ‘When you’re in charge of making a difference, there is no limit to what you can do’.1 Facebook’s offices also seek to convey this message. Facebook’s newest headquarters in Menlo Park, California is a single 40,319 m2 floor – the world’s largest open-plan floor – to foster the free exchange of ideas. The building, designed by Frank Gehry, features desks with no cubicles or partitions, clustered in specific configurations called ‘neighbourhoods’, which are linked by curving ‘pathways’. The lack of individual offices means that even Mark Zuckerberg, founder and CEO, sits at a simple white desk. Above this inward-facing neighbourhood community is a 36,421 m2 green roof, which provides 804 metres of winding nature pathways, 400 trees, hidden alcoves for private relaxation, and benches for group brainstorming sessions. The connection with nature presents the image of an idyllic environment while also contributing to the possibilities for spontaneous interaction that may ultimately result in bottom-line benefits. New recruits applaud the design as emblematic of Facebook’s focus on fostering an environment that is conducive to collaboration, the free flow of information, and openness and transparency.2 Although seasoned employees eventually become resistant to the Kool-Aid, the allure is sweet enough to encourage new recruits to go through the doors.

While Menlo Park is a suburban idyll, it also houses several inner-city characteristics in the form of urban amenities. Interestingly, this all-in-one urban imaginarium is being replicated by Big Tech irrespective of location. For example, Canada’s Google engineering headquarters in downtown Kitchener, Ontario, started out with 17, 181 m2 of campus-like office space equipped with a cafeteria, multiple cafés (in-between ‘neighbourhoods’), a climbing wall, gym, and a library with a fireplace, armchairs and a secret room. It is a city within a city – a community centre, an office and a home – to keep the workers in situ, within the comfort of their own living room.

The twentieth-century white-collar office and today’s modern ‘coffice’3 version share the impulse to dazzle with design, seeking to symbolise the progressiveness of the professions they house. For the twentieth-century office this was a deliberate separation between factory labour and the rise of the white-collar worker. The office symbolised a break from the strain and tedium of factory work and offered the class-based promise of upward social mobility. For the modern-day co-working, café-like office (hence the ‘coffice’), the promise is a break from a rigid hierarchy, a departure from collared attire towards a no-collared ‘athleisure’ class. It is a celebration of partnerships and collaboration, and intellectual and creative stimulation, in a rapidly digitising world.4 In other words, both iterations are based on grand visions of what the future of work ought to be and look like, and rely heavily on design to get the message across. More specifically, the architecture and symbolism generate excitement about the future as an employee. In the twentieth-century office, the design itself suggests possibility: a mid-level employee is just a promotion away from the glass office. By contrast, the modern office removes the cubicles and that unattainable glass office to present an open-plan floor and a flat hierarchy where there is no need to think about a promotion, because there are no physical barriers to overcome. These iterations show how the corporation has always used space to organise, manage, and control the working class.

All of this is to say that design is strategic and deliberate. To uncover the machinations of a new workplace culture, consider the design of its setting. To understand the modern corporation and its influence, however, we need to go beyond the office and look at the city as a whole. This is because a major difference between the twentieth-century office and the coffice is modern work itself, a growing proportion of which is mobile, flexible and project-based – so-called gig work. Workers themselves need to be mobile, flexible and networked in order to land their next gig.5 They cannot be contained, since they are expected to be ‘temporarily omnipresent’ and able to access their work from anywhere and at any time. As wired mobility becomes more pervasive, the outside of the office becomes just as important to the modern corporation as the inside. Today’s workplace needs to rival any other place in the city with good Wi-Fi. In other words, it brings the city to the worker and, to the delight of corporate management, there will be no need to leave. This is also why today’s corporate aesthetic sprawls across the city as a means to manage the no-collar class.

In 2004, Google’s decision to base its European Middle Eastern and Asian (EMEA) headquarters in Dublin’s city centre proved pivotal for the dockland’s revitalisation. Attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) was never too challenging in Ireland due to a tax-avoidance strategy that allowed multinational corporations a comparatively low corporate tax rate of 12.5%.6 Ericsson and IBM had a presence in Ireland from the 1950s, Hewlett-Packard (HP) arrived in the 1970s, with Apple, Intel, Microsoft, and Oracle all arriving in the 1980s. Google’s decision to locate in the docklands surprised the Irish since until then tech companies were building campuses outside the urban core.

Pajević, 2019

Shipping ports along the river, docklands, railyards in the city centre, and historic locations of manufacturing activity fell into dereliction as cities decentralised and companies outsourced industrial activity. Given their central location and proximity to services, public transport, and young and hip urban talent, however, these post-industrial sites are now highly coveted by Big Tech.

Pajević, 2019

What makes city centres or ‘cool’ inner-city districts particularly fashionable is their historical value, or rather historical sites whose functions have been ‘switched off’ by modern technologies. Abandoned industrial sites, old factories and analogue cinemas tend to attract the modern corporation. More importantly, these prime locations at the heart of the bustling city come with a cheap price tag. Their re-appropriation is intentional: by tackling the decay and decline produced by previous iterations of progress, the modern corporation asserts itself as the ultimate preserver of the past – a benevolent history buff. In the case of Dublin, Google saved the docklands; in the case of Kitchener, Google saved the textile and rubber factory. They did not do it alone, however: in both cases a significant chunk of public funding aided the branding that is meant to get the start-ups to flock.

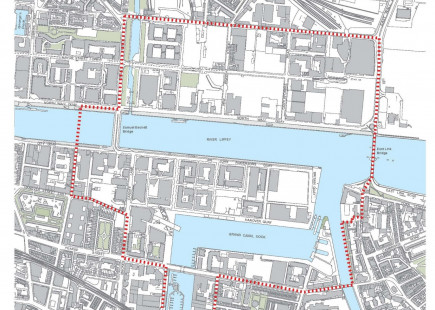

In Dublin, Google’s arrival created a path for other tech companies to follow. Promises of rampant growth fell apart though in the 2008–2009 recession. By fiat, all development was halted and the landscape of the Dublin docklands was left with the skeletons of half-developed construction sites. Various policies enacted by two key institutions, aided by promotional campaigns, facilitated the rapid removal of these unfinished structures. Of primary importance was the National Asset Management Agency (NAMA), a state institution with bank and real-estate brokerage-like abilities to purchase toxic assets, stabilise the banking sector, and revive the economy by stimulating the flow of credit. NAMA bailed out Irish developers, awarding €32 billion in government-backed assets, and then set out to court global capital to the docklands where it held the largest concentration of assets. More specifically, NAMA knew that local developers were strapped for cash, making the only profitable solution to attract global capital. NAMA also asserted itself during the masterplan development for the docklands. In 2013, Dublin City Council (DCC) prepared a planning scheme to government development over a 660,000 m2 strategic development zone (SDZ) at the North Lotts and Grand Canal Dock.

Dublin City Council

To streamline development on this portion of the docklands surrounding Google, DCC overlaid the SDZ boundary with a ‘fast-track’ provision, which prevents the public from appealing against any plan it has approved, thus erasing any opportunities for the public to oppose developments in the pipeline. It was during the appeal period that NAMA pushed for developmental leeway that would ensure flexibility in the types of construction that were acceptable in the SDZ. NAMA used these provisions to attract global capital that prioritises commercial and office property development over much-needed residential construction.

Ireland’s Industrial Development Authority facilitated the development of the tech sector by spending €2 million on a marketing campaign to promote Ireland as an innovation and technology hub during the height of the recession. This is a small sum in comparison to Enterprise Ireland, a government agency, which approved €10 million for an international start-up fund to encourage entrepreneurs to locate in Ireland.

Today, there are 34 companies in the SDZ, with tech-sector development spilling over all sides of its boundary. Indeed, according to the Cushman & Wakefield Office Trend report, in the first quarter of 2019, 47% of Dublin’s office space has been occupied by the tech sector, and 59% of the office space that is currently under construction has already been reserved. Annually, rents are rising by 4.2%.7 This may not seem like much, but given the volatility of the economy and the notorious fickleness of the tech sector, it is enough to push smaller tech and non-tech businesses entirely out of the market for office space.

The same can be said of KCW in Ontario. The tri-city area is a modest cluster of small and medium-sized industrial towns. All three cities have an innovation district or an equivalent, an innovation centre, and a policy focus on tech-oriented development. Key investors include all three levels of government (federal, provincial and municipal) as well as venture capital from across and beyond Canada. Since the election of Donald Trump in 2016, the not-so-secret hope is that by investing in KCW, a significant chunk of Silicon Valley’s business will look to Canada for a better alternative. The ‘investment fund’ that propelled the revitalisation of Kitchener’s downtown core was an impressive CAN $100 million-plus change of public funds, starting out with a space for education, followed by space for condo development, and concluded with workplaces. The general aim is to transform unused factory spaces into potential anchors for tech talent. This talent is often scouted at one of the university’s many incubators (hence the focus on education), as well as via Communitech – a public–private innovation centre to which young tech entrepreneurs apply for a temporary residency and a chance to showcase their products to potential investors. Indeed, the university and Communitech are often credited for giving Kitchener its facelift, as is the arrival of Google: they have transformed former tanneries and factories into sandpits for the no-collar techies, motivating corporations seeking these workers to do the same. Over the past decade, downtown Kitchener has seen its decrepit real estate transform into glossy condos, fancy workplaces, and designer cafés – and it continues.

Although it cannot be pinned to the arrival of Google per se, local real estate brokers do acknowledge the role that the company plays in attracting new home buyers and investors to Kitchener-Waterloo. However, the lack of available homes for sale, paired with rising demand and speculation over future development, are heating up the market through record-breaking bidding wars. In an unprecedented building boom, the Kitchener core will be drastically transformed with CAN$1 billion in office and residential investment to try and alleviate the pressure on the real estate market. While these efforts may stabilize the market, prices will likely remain the same.

Efforts to build a regional brand — in the form of an Innovation Corridor — have concurrently inspired the Toronto-based real-estate investment trust company, Allied Properties, to seek out opportunities for sleek office development in Kitchener-Waterloo. As in the Dublin case, the marketing efforts target the live-work-play lifestyle that developers – and employers – regard as the de facto needs of these profit-creating workers. In Ontario, developers, advertising agencies, and brokers are part of a continuing effort to bring ‘Condo Culture’ to KCW. Their efforts seem to be paying off, but who is paying? Housing prices have doubled in 2018 alone.

Pajević, 2019

Meanwhile, outer-city office parks are emptying in favour of these new downtown offices. Established companies, like Deloitte, have followed in Google’s footsteps and revitalised yet another downtown historic site to mark its transition to tech. Meanwhile Google has announced an expansion to an 11-storey building adjacent to its current facility, adding another 27,870 m2 of prime (Class A) office space to the heart of downtown Kitchener. According to the Waterloo Region Office Snapshot by Cushman & Wakefield, the Kitchener and Waterloo rents for Class A office space are rising. Interestingly, the rent for not state-of-the-art offices (Class B) seems to be catching up, which begs the question: if prime offices are already out of reach, and secondary options are also heading in that direction, what remains and for whom?8 In Kitchener, although the public sector is making an effort to combat the negative effects of gentrification by attempting to partner with the tech community and negotiate better outcomes, it is unthinkable to knock the needs of the corporation from the top of the list. Business as usual renders these discussions and any action-oriented outcomes meaningless.

As tech moves to the city centre, this becomes problematic for its collective spaces. Indeed, the old is replaced with the new: old warehouses are now filled with restaurants, shops and boutique offices. Who are these ‘new’ spaces for? Is their revitalisation intended for everyone or just for the few? Why do cities continue to fund enterprises that revamp them to look like Silicon Valley? Because – and we cannot over-emphasise this – cities matter for today’s corporation. The promise of new jobs, economic growth and urban development blankets policy discussions, resulting in the creation of privileged spaces in the revitalising city.9 These spaces syphon funding from public coffers in the expectation of trickle-down economics to the benefit of the city, the region and the nation.

‘Time for a coffee then, and to enjoy the sunshine and buzz of the Silicon Docks. The surrounding skyline peppered with cranes testifies to the continuing growth and signals the fact the recession is well and truly over in this area. The regeneration of this once blighted place has been a revolutionary success’, says Kevin Barrington for Dublin City Council.10

Underneath the glossy aesthetic of the Silicon Docks and Silicon Valley North is a lacklustre reality. Big Tech located there are self-provisioning fortresses. In addition, these corporations draw on a continuous supply of international talent, effectively creating an isolated bubble existing apart from the rest of the city.

Growing in tandem with the Silicon Docks is the number of people with no home or no roof of their own. Although there are many factors contributing to this phenomenon, the connection between the increasing presence of Big Tech in Dublin and affordable housing are rarely acknowledged, and sometimes, openly refuted.11 The Canadian case is similar. Although the public sector in KCW recognises that the tech boom is widening the social gap among its residents, there is an air of hope that the market will provide a solution – and that the tech corporations will extend a helping hand.

For Big Tech, however, the priority is attracting and retaining talent, so the premium is on the ‘cultural’ experience of place rather than its social value. For this reason, the shape and character of real estate occupied by the corporation, and the cachet a city can bring to the company’s brand, seem to be more important than before – and more expensive.

For many Dubliners, the Silicon Docks is a visible come-back story of a small island economy once called the Celtic Tiger, then temporarily devastated by the global recession, but now looking towards brighter, more promising, horizons. Similarly, KCW, formerly a seat of the automobile, rubber and leather industries, is working on its own come-back story. The same can be said of Detroit, St Louis, and many other post-industrial cities across North America. Becoming and maintaining the spotlight as an investible city requires effort, however, along with the seal of approval that comes from heavyweight corporations establishing a presence.12

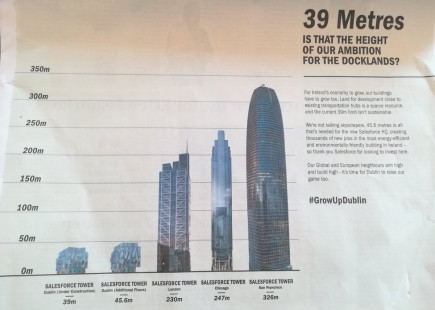

Times Ireland 21 April 2019

But it is all about profit. The emergence of the Silicon Docks reflects the type of urbanism that looks to exchange value rather than use value. In April 2019, Johnny Ronan, a businessman and developer, took out a series of paid advertisements in the Irish Times. His aim was to obtain approval for adding floors to the Salesforce Tower he is building. Ronan petitioned the High Court to amend height regulations. US-based Salesforce and Ireland’s Industrial Development Authority petitioned in his favour. The major opposition has been from Dubliners who take pride in their human-scale city, while skyscrapers would forever alter the skyline. The argument in favour of increasing building heights is disturbingly tied to attracting more companies; about projecting Dublin’s ambition as a competitor rather than favouring building heights to alleviate the crisis in available and affordable housing in Dublin.

The arrival of Big Tech in the urban sphere changes neighbourhoods and districts. It raises property prices and rents, displacing communities whose lifestyles cannot fit into this cultural mould. Dublin is now consistently ranked as one of the most expensive cities in Europe for rental accommodation.13 One reason for this is the shift towards construction of profit driven developments rather than affordable quality housing. Recent innovations in the Dublin market include co-living apartments—dormitory-like bedrooms with communal kitchen and living quarters, and aparthotels--short- and medium-term let serviced apartments. Ireland’s historic owner-occupied model has been shaken by a rental culture associated with the footloose tech-worker. The influx of no-collar techies seeking to live close to work have significant advantages due to their ability to either afford newly built residential units or to deposit two or more months’ rent to secure highly coveted accommodations. The remainder of the population is stuck fighting for the limited remaining rental options in a country lacking adequate tenant protections or commuting long distances to reach work. Where do we go from here? How do we tackle these rising rents and ensure that spaces remain affordable and accessible to non-tech players?

Through their demands, tech companies weight the scales in their favour by leveraging development incentives, tax subsidies, and other benefits while also taking advantage of state-paid infrastructure, city services, and access to talent. Cities across the globe with a strong tech presence struggle with the negative externalities of being a global city: traffic congestion, lack of affordable housing, displacement of long-term residents, homelessness, and crumbling infrastructure. Silicon Valley, the beacon for these developments and home to the original tech-saviours, is in similar disarray with non-stop traffic jams and such desperation for housing that even the no-collar techies are living in their cars. Public officials fail to address these persistent social issues, focusing instead on seeking to attract the very companies that might ultimately destroy the liveability and vibrancy of their city. Worse still is the entrepreneurial spirit that prevails among rising tech-saviours who see Silicon Valley as a rite of passage: if you make it there, you will make it anywhere.

Cultural change is often intangible and harder to resist, so activists must look for clues – for tangible information on what, where and how Big Tech exerts its influence, and for ideas on how to fight back against the glossy narrative and demand genuine solutions to pressing issues. We have focused on one symptom of the modern corporation’s hegemony – the use and abuse of the built environment. There are, however, many more.

Change is inevitable – but change without checks is destructive. While tech culture repeatedly garners worldwide attention, it fails to live up to its own hype and, by extension, its own promises. Under the guise of innovation and creativity the corporation seeks to remake the worker, the workplace and cities, while receiving large public support to do so. Our aim is not to diminish the importance of creativity, innovation and technology to overall social progress, but rather to highlight the pitfalls of a dominating narrative and a policy focus on tech culture. These corporations offer no guarantee of economic success and thriving urban environments.

Activists in New York City recognised this when they fought against Amazon HQ2. These activists knew what was at stake for their communities and for their public coffers. That a city dared to challenge the orthodoxy embracing the digital giants – saying the emperor has no clothes – is a good start. But is it enough? The challenge is to find pressure points for resistance. There is no simple step-by-step manual for beating this opponent. The answer goes far beyond legislation, improving policies, public participation, activism, and transparency – it calls for a paradigm shift. This is where it gets tricky, leaving us at a loss for how to tackle corporate hegemony.

What is more, this shift requires cooperation and consensus across multiple geographic scales. It is not enough to shut down the modern corporation in one place, because it will inevitably spring up elsewhere. The tentacles of the modern corporation extend far and beyond a single location. Rather than engage in a ‘whack-a-mole’ game14 with the modern corporation, cities across the globe – and their governments – must agree that regulation is required, and that multiple issues need addressing swiftly and simultaneously. Perhaps it all starts with the acceptance of one simple truth: the modern corporation will not bring us better jobs or financial security, and it will not improve our cities. In short, the modern corporation and its legion of tech-saviours will not save us. We have argued for the importance of taking place seriously, and establishing the ground rules corporations must abide by, rather than – often pathetically – the reverse.

Notes

1 Facebook webpage, Careers, 2018. https://www.facebook.com/careers/

2 Consider the irony of the importance of transparency. Recently, Facebook faced a number of lawsuits related to Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation for coercing users to share personal data and from the California court system for using its apps to spy on users and their friends. In addition, Facebook is accused of failing to protect users from Cambridge Analytica, a data analytics firm that worked with Trump’s election campaign in the US and the Brexit campaign in the UK from harvesting millions of Facebook profiles to influence votes. The point here is that the opulent office design is a mask for darker practices.

3 Term first used in The Guardian on the future of work, January 2014. https://www.theguardian.com/money/shortcuts/2014/jan/05/coffice-future-of-work

4 For a detailed, well-researched account of changes in the landscape of work, see Saval, N. (2014) Cubed: A Secret History of the Workplace,. New York, NY: Anchor Books.

5 Two good publications on changes in ways of working are by Elliott, A. and Urry, J. (2010) Mobile Lives. Abingdon: Routledge and Boltanski, L. and Chiapello, E. (2018)The New Spirit of Capitalism (trans. by G. Elliot). London: Verso.

6 In comparison to the corporate tax rate in France of 34.4% and the US rate of 38.9%.

7 See Cushman & Wakefield, Dublin Office Market Q2 2019. http://www.cushmanwakefield.ie/en-gb/research-and-insight/2019/dublin-office-market-q2-2019

8 See Cushman & Wakefield, Waterloo Region Office Snapshot Q2 2019. http://www.cushmanwakefield.ca/en/research-and-insight/canada/waterloo-region-office-snapshot

9 See Sharon Zukin’s critical take on urban tech-based development in The Architect’s Newspaper, May 2019. https://archpaper.com/2019/05/urban-tech-landscape/

10 See ‘How Dublin Works: Digital Docklands’. https://dublin.ie/work/stories/how-dublin-works-dublin-docklands/

11 This parallels the reaction by elected officials on the 2016 ruling by the European Commission for the Irish government to recover €14.3 billion in back-taxes from Apple for using Ireland as a tax haven. Discussions with Dublin City Council officials during this time period revealed disdain for the ruling.

12 There is a reason why public officials in cities across the United States were willing to offer millions in incentive packages for Amazon to build its second headquarters in their jurisdiction. Amazon selected New York City and the Washington, DC metropolitan area – not post-industrial cities in desperate need of resources such as a Detroit or St. Louis.

13 See Mercer’s 2019 Cost of Living Rankings where Dublin ranks as the most expensive city in Europe. https://mobilityexchange.mercer.com/Insights/cost-of-living-rankings, See also ECA International’s Cost of Living study where Dublin ranks as the fifth most expensive city in Europe https://www.eca-international.com/services/data/allowances-benefits/cost-of-living.

14 A carnival game in which the objective is to whack the head of a mole popping out of hole only to have it spring up in another hole.